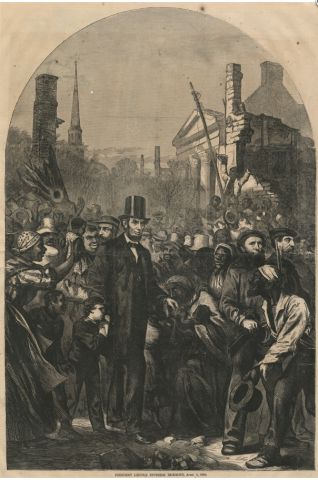

"President Lincoln Entering Richmond — April 4, 1865"

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)

Harper’s Weekly, February 24, 1866

Wood engraving on paper

Georgetown University Art Collection, 1111.1.5646

June 19, 2024

The Booth Family Center for Special Collections displayed "President Lincoln Entering Richmond — April 4, 1865," a wood engraving by Thomas Nast, to mark Juneteenth. Mary Beth Corrigan, Librarian for Collections on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation, explores the relationship of this work to the public memory of President Abraham Lincoln and emancipation.

"President Lincoln Entering Richmond — April 4, 1865," a wood engraving by Thomas Nast, appeared in Harper’s Weekly, one of the nation’s most popular and trusted news sources, on February 24, 1866.1 Nast visually reconstructed the visit of Lincoln, victorious after the evacuation of Richmond. Hundreds of jubilant Black and white Richmonders greeted him, transforming his visit to survey the destruction of Richmond and meet Union generals transformed into a celebration of his role in emancipation. Nast’s image has become iconic, playing an important role in the public memory of Abraham Lincoln and emancipation.

Harper’s Weekly did not provide contemporaneous coverage of Lincoln’s visit in April 1865. Instead, the events that preceded Lincoln’s visit dominated the pages of Harper’s Weekly: the retreat of Confederate soldiers, the fires set by them as they evacuated the city, and the occupation by Black and white Union soldiers.2 In the following weeks, the surrender by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House on April 9 and the assassination of Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth on April 14 dominated the pages of Harper’s Weekly.3 It is unclear how Nast composed his portrait, although it seems probable that he drew upon oral accounts from eyewitnesses and not a photographic image of the scene.

Nast’s composition was instead part of a commemoration of the first posthumous birthday celebrated for Abraham Lincoln on April 12, 1866. It was a counterpoint to an address delivered by historian George Bancroft to Congress that praised Lincoln’s earnestness as a politician, his courage in waging the Civil War, and the tragedy of his assassination.4 The editors of Harper’s Weekly maintained that Bancroft’s well-reasoned piece failed to recognize that “posterity will see in [Lincoln] a greater man than his contemporaries will acknowledge.” They elaborated that no event in Lincoln’s life would be remembered as fondly as the day that Lincoln entered Richmond: “Crowds thronged the streets, and chief and eager among them the emancipated race, which called Heaven’s benediction upon their Liberator and Friend as he passed by.”5

Nast captured the spirit of Lincoln’s visit. Although eyewitnesses disagree on details, the broad outlines of the event are undisputed. Within forty-eight hours of receiving word of the evacuation of Richmond by Confederate forces, Lincoln traveled from Petersburg to Richmond on a steamer commanded by Admiral David Dixon Porter. Without any public announcement or security beyond the twelve sailors on that ship, President Abraham Lincoln stepped off a barge docked on the James River. Black men, women, and children – already celebrating their emancipation — recognized him immediately. Jubilant at the sight of Lincoln, crowds formed shouting and singing hymns of praise, with several individuals kneeling at his feet and blocking his path.6

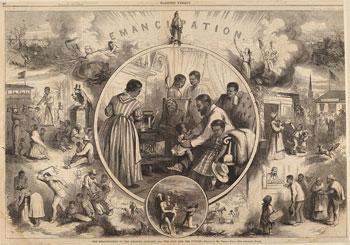

"The Emancipation of the Negroes, January 1863 — the Past and the Future"

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)

Harper’s Weekly, January 24, 1863

Wood engraving on paper

Georgetown University Art Collection, 2019.1.5

In his 1866 engraving, Nast returned to a theme of his previous artwork: the veneration of Lincoln by newly-freed people. Shortly after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, Harper’s Weekly published a Nast print, “The Emancipation of the Negroes, January 1863 — The Past and Future,” one so popular that it was widely reprinted as a poster after Lincoln’s assassination. A series of vignettes depicted the horrors of slavery — the cruelty of slave auctions, overseers, and slave catchers — that gave way to the hopes for freedom — family lives nurtured by education, community gatherings, and payment of wages. Lincoln was featured in its central image: his portrait was the principal decoration in the living area of a multi-generational Black family experiencing the type of domesticity denied to enslaved people.7 Nast had also depicted the feelings of Black mourners of Lincoln in the wood engraving, “Our Martyred President,” published on June 10, 1865. With Lincoln depicted as a ghostly presence at its center, an image of a praying Black family is depicted with the subheading “Our Savior.”8

Nast’s portrayal of Lincoln in Richmond conveyed the veneration of Black Richmonders of Lincoln. Formerly enslaved people often saw parallels between Lincoln and Biblical figures, such as Moses, that persisted among themselves and their children.9 In his reminiscences, Admiral Porter recalled that, as soon as Lincoln stepped foot on the soil of Richmond, a Black man greeted him calling him the “great Messiah.”10 Nast illustrated those feelings by depicting a woman kissing Lincoln’s hand, a gesture typically reserved for royalty and the clergy in Europe.

The selection of the visit to Richmond as its seminal image of Lincoln by Nast and his editors suggested the finality of emancipation. However, the timeline of emancipation belies such a simple supposition. By providing freedom only to those enslaved within the “rebellious states,” the Emancipation Proclamation did not provide formerly enslaved people the full legal protections of the federal government. Even as the jubilant Black Richmonders celebrated the imminent end of the war and their emancipation, slavery was not completely defeated. The Thirteenth Amendment had passed Congress on January 31, 1865, and still needed three out of every four states to ratify it.11 Slavery still existed in the areas that remained under Confederate control. In western Texas, there was no formal declaration of the end of slavery until June 19, 1865, when 2,000 Union troops arrived in Galveston and posted notice that 250,000 Black people were freed. The ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment followed in December 1865.

The image of Lincoln as the Great Emancipator suggests the limits of emancipation from the perspective of Nast and his Harper’s Weekly editors. Their ambivalence towards civil equality was revealed during the 1870s, as they blamed the corruption of Republican governments in Southern states on Black voters. Nast compared them to the Irish voters who supported Tammany and other machines in his December 9, 1876 cartoon “The Ignorant Voters – Honors Are Easy.”12 This cartoon depicted a balanced scale to demonstrate the equally harmful impact of the Irish and Black vote on the governments North and South. Nast used pernicious stereotypes; he depicted the Irish man as simian, with an ape-like face and hands, and the Black man as a coon caricature, with a broad smile, big lips, and wearing no shoes or hat.13

As other white narrators of the history of emancipation, Harper’s Weekly could only accept emancipation without civil equality. The valorization of Lincoln’s role in emancipation suggests the fight for equality ended in 1865 and that Black people played a subordinate role in emancipation. Yet, the generations of Black Americans who celebrate emancipation with parades, picnics, and community events on Juneteenth have used the day to educate each other and to organize to fight for the equality that they have yet to achieve. Their memory of emancipation – including their views of Lincoln – should replace those that diminish the role of Black people in the struggle for their own equality.

Notes

- Thomas Nast, “President Lincoln Entering Richmond, April 4, 1865,” Harper’s Weekly (New York), February 24, 1865, pp. 120-121, accessed June 26, 2024.

- “The Union Army Entering Richmond, April 3, 1865, Harper’s Weekly (New York), April 22, 1865, pp. 248-249, accessed June 26, 2024.

- "The Assassination of President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre on the Night of April 14, 1865,” and “The Assassination of President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre – After the Act,” Harper’s Weekly (New York), April 29, 1865, p. 260, accessed June 26, 2024.

- David Brainerd Williamson and George Bancroft, Illustrated Life, Services, Martyrdom and Funeral of Abraham Lincoln, Sixteenth President of the United States with a Full Account of the Imposing Ceremonies at the National Capital, on February 12th, 1866, and the Hon. George Bancroft’s Oration, Delivered on the Occasion (Philadelphia: T.B. Peterson and Bros., 1866), accessed June 26, 2024.

- “Abraham Lincoln,” Harper’s Weekly (New York), February 24, 1866, p. 114, accessed June 26, 2024.

- David Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1885), pp. 288-303, accessed June 26, 2024.

- For the interpretation of “The Emancipation of the Negroes, January 1863 – The Past and the Future,” see “Emancipation,” Harper’s Weekly (New York), January 24, 1863, p. 55, accessed June 26, 2024.

- “Abraham Lincoln, Our Martyred President,” Harper’s Weekly (New York), June 10, 1865, p. 360, accessed June 26, 2024.

- John E Washington, They Knew Lincoln, ed. by Kate Masur (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018), ix-lxxx.

- Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War, p. 295, accessed June 26, 2024.

- For the text of the Thirteenth Amendment, see “Milestone Documents: 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Abolition of Slavery (1865),” National Archives and Records Administration, accessed June 26, 2024.

- Thomas Nast, “The Ignorant Vote – the Honors are Easy,” Harper’s Weekly (New York), December 9, 1876, p. 1, accessed June 26, 2024.

- “The Coon Caricature,” Jim Crow Museum, accessed June 26, 2024.