The Woodstock Theological Library lost a great friend this last Saturday. In honor of Gerard Mannion, we are reposting an entry he kindly wrote for us two years ago.

------------------------------------------

In honor of Saint Patrick's Day, Woodstock Theological Library (WTL) is delighted to have a guest blogger: Professor Gerard Mannion, Joseph and Winifred Amaturo Chair in Catholic Studies of Georgetown’s Theology Department. Here is his insightful analysis of the history and context of one of our manuscripts:

One of the precious manuscripts held in the WTL (which can also be accessed, as a digital resource) is the 17th century History of Ireland, written by priest and poet Seathrún Céitinn (the Anglicized version of his name, under which the MS is catalogued being Geoffrey Keating) A native of Tipperary, he lived from c. 1569 to c. 1644. He lived during one of the many turbulent centuries in the history of relations between Ireland and England. Because Catholics could not receive a university education in Ireland at that time, like many, he had to leave the country and study at one of the numerous Irish Colleges established all over the continent specifically for Irish Catholics. Keating went to the college in Bordeaux, France, where he completed the Doctor of Divinity degree awarded by the main university there. His History of Ireland was written in early modern Irish (entitled Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, meaning the ‘Foundation of Knowledge on Ireland’), which charts the history of Ireland from the earliest of times until the arrival of the Norman invaders in the twelfth century.

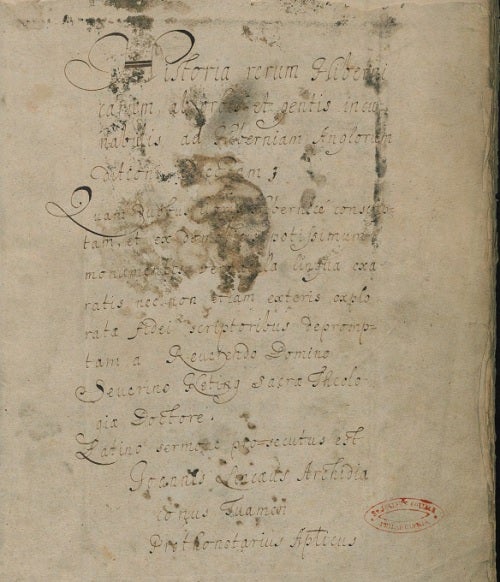

Hence the Latin title: Historia rerum Hibernicarum ab orbs et gentis incunabulis ad Hiberniam Anglorum ditioni adjectam. Loosely translated it means ‘The History of Ireland from the beginning of the world until Ireland became added to the English dominium’. The English would not allow it to be printed owing to the strong Catholic leanings of the work and the Latin translation was most likely produced on the continent. It circulated in hand-written manuscript form in Irish, Latin and English until finally an adaptation (rather than precise replication) of the history was printed in 1723.

It is a Latin hand-written manuscript that we have at Georgetown (pictured above) based on a Latin edition of the work believed to have been printed between 1650 and 1672.

It is a Latin hand-written manuscript that we have at Georgetown (pictured above) based on a Latin edition of the work believed to have been printed between 1650 and 1672.

The work’s key value lies in the window it sheds on the self-understanding and perception of the Irish of themselves and their history of the seventeenth century during those troubled times. Some contemporaries questioned the precise nature of Keating’s sources but much of what it says about ancient Ireland can indeed be confirmed from other and often more ancient sources. Keating was indeed a gifted historian after the fashion of his times – skillfully blending fact, interpretation, legend, myth and rhetoric. But, then again, it could be argued that most historians even to this day work with varying elements of each of these characteristics too!

The picture it gives is of the distinctive, noble and proud ancient Irish kingdoms with a pronounced cultural history of their own and one of the first vernacular languages in Europe (in fact Irish is believed to be the very first language aside from Latin to have a written form). Ireland was a sovereign, independent kingdom (of kingdoms) which, although it became the home of various wandering tribal peoples throughout its ancient history, had never once been conquered. Keating goes to some lengths to try to portray the Norman rulers of much of Ireland from the twelfth century onwards as simply being the successors of the earlier Irish kings and therefore, were also endorsed by the people rather than conquerors as such. In particular, through the endorsement of their rule by some of the ancient Irish leaders themselves through an agreement with the pope in the twelfth century that this was in Ireland’s interests that the Normans should play such a role in their land.

Keating also tries to establish a common lineage between the contemporary Stuart Kings of Britain and the same ancient tribes from whom many of the Irish were descended.

The extended preface criticizes a number of earlier (English) historians for their inaccurate and demeaning portrayal of Ireland in their own histories. This, too reflected the political climate of the time as James had become the first Stuart monarch to accede to the British throne in 1603 with his son, Charles I succeeding him in 1625. For those Catholics in Ireland with some ancestry linked to earlier Norman settlers (via England hence known as the ‘Old English), of which Keating was one, due o his own Norman ancestry the new monarchy represented a time of both opportunity and trepidation for Ireland.

The work therefore gives a social and political vision of ancient Ireland that might inspire and inform a new social and political order in the (then) present day. For example, Keating makes much of the fact that the High Kings of Ireland were appointed through consensus of the people rather through birthright and hereditary mechanisms.

The work also represents a distinctive contribution to the continued Catholic responses to the Protestant Reformation and it weaves together the history of Irish society and the Irish church and portrays the latter as integral to the flourishing for the former. Again, this speaks to the times of its author (who returned to Ireland to minister as a priest) as much as to the history of ancient Ireland although, once again, much older sources do indeed demonstrate the intricate interweaving of Irish social and ecclesial life and practices in general.

As Irish people and so many others all over the world celebrate St Patrick’s Day today, it is fitting to commemorate this history of Ireland which divided that history into three epochs – pre-Christian, the era of early Christian Ireland after the arrival of St Patrick and finally the period of the Normans’ arrival in Ireland. It should be noted however, that much older sources demonstrate that there were Christians in Ireland before St Patrick, although Patrick did indeed consolidate the faith in Ireland and converted countless numbers, including many influential societal leaders.

One could argue that the actual history of ancient Ireland is even more fascinating than Keating’s skillful blending of contemporary concerns with ancient sources and legends suggests. Ever since the country’s embracing of Christianity in the 5th Century, Ireland, of course, soon came to be known a land of ‘saints and scholars’. Christianity in medieval Ireland did indeed blend with the unique cultural and social traditions of that land and developed into a very distinctive and progressively inculturated form of the Christian faith, indeed into something quite distinctive from the character of ‘Roman Christianity’ of the era.

The rich customs and traditions of ancient Irish society that Keating mentions were indeed blended with the new faith brought to the land. Anyone who visits some of Ireland’s most ancient, historic and stunningly beautiful natural sites can immerse themselves into this ancient cultural world still, including the worlds of those such as Saints Patrick, Brigid, Kevin and Columbanus (the latter of which helped convert so many lands throughout Europe and remains honored buried in Bobbio, Italy to this day). They may learn how Christianity flourished through the many schools of the land and how Ireland sent its missionaries far and wide across Europe, leaving a deep and lasting impression upon European culture, the impact of which can be seen to this day.

Most surprising of all, perhaps, they might learn that much of what is most distinctive about ‘Celtic’ Christianity in its Irish context actually owes much to the characteristics and ways of the people who predate the time of the Celts in that land. They would hear about and discuss the clashes between the ‘Celtic’ Christians and their ‘Roman’ counterparts and how practices differed significantly in Ireland from elsewhere, whether this be that Irish monks wore their hair long as opposed to the Roman tonsure, to the innovation which Irish monks introduced in order to offer a process of healing and reconciliation for those troubled by their transgressions – the practice which became private confession. They would learn how women enjoyed greater freedom and opportunity in many parts of ancient Ireland and could be political (even military) as well as religious leaders, as well as having a right to education and even to practice law.

They would also be immersed in the story of how, in Western Europe’s dark ages, after the final demise of the Roman Empire, Ireland’s remote location kept deep learning and scholarship alive, including as a last outpost where some of the classics of ancient Greek and Latin literature were well known and read and so how Irish scholars, ‘saved civilization’, as one study has put it (by Thomas Cahill, a fascinating read that perhaps shares much in common with Keating’s own idealized narrative in parts!). As already mentioned, ancient Irish is believed to be Europe’s first vernacular language to have its own literary form. So, as well as an historical and religious focus, anyone delving deep into the history of this most westerly lands of Europe would be immersed in exploring social, cultural and indeed political issues of those times.

They would see and hear how religion is always found in inculturated forms – that is to say – that a particular faith by necessity becomes refracted through and in turn changed and developed by the cultural milieu in which it is lived out and how there is a profound two-way relationship of influence between religion and the cultures in which it is practiced. Such a journey throughout history has deep implications for religion in differing communities in our world, as well as for the relations between differing branches of the same faith, including Christianity, today.

So on St Patrick’s Day it is fitting to raise a toast to this noble scholar who helped chronicle not simply the story and profound impact of Patrick and Christianity upon Ireland, but helped demonstrate why the Irish are given to celebrate the land of their birth and its many ancient heroes, heroines and customs. Keating's History of Ireland helps us understand why this day, March 17th, is so special to so many, many millions around the globe.

Entry written by Gerard Mannion on 1/17/2017