Introduction

In recognition of an important recent acquisition, the Fairchild Gallery presents Audubon's Birds of America: Selections from the "Amsterdam Edition", with vivid illustrations by naturalist and artist John James Audubon (1785 -1851).

In early 2005, the Georgetown University Library received a generous gift of selections from the so-called "Amsterdam Edition", a handsome set of a "double elephant folio" (39 7/16 x 26 5/16 inches) of high-quality photolithograph reproductions faithful to Audubon's original illustration sizes. The Amsterdam Edition was produced between 1971 and 1972 by the Johnson Reprint Company, of New York (U.S.A.) and Amsterdam (The Netherlands). Prof. Gary Filerman, Director of the Health Systems Administration Program at Georgetown University's School of Nursing and Health Studies, and Melvin Goldfein were the donors of the Amsterdam Edition, adding a landmark work to the Library's strong collection of art on paper from the United States.

The Amsterdam Edition was part of a tradition of reproducing Audubon's work that began with Audubon himself, when, in 1840, he and his sons had published in Philadelphia an edition on 10 x 6 1/4 inch sheets: Lithographers used a camera lucida, a device with lenses that could project a reduced-sized image onto a surface for copying. From chromolithographic techniques of the nineteenth century, to the photomechanical processes in the next century (of which the Amsterdam Edition was, at its time, one of the most sophisticated), to the digital and electronic printing of recent decades, publishers have served an enthusiasm for Audubon's work that has waned little since his lifetime. 1

In addition to these selections from the Audubon portfolio, the exhibition features an important 1840 edition from Philadelphia of The Birds of America, along with the first volume (1831) of Audubon's Ornithological Biography; and later Audubon editions that have been collected by the Georgetown University Library. To illustrate the works that preceded and inspired Audubon (because, in some instances, he thought that his own work was better), the exhibition includes volumes of the Histoire naturelle des oiseaux (1707-1788), compiled by Georges Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon 2; and Alexander Wilson's 1808-1814 American Ornithology. (Audubon and Wilson met on one fateful day; "Posterity, encouraged by the partisan accounts of contemporaries, has chosen to treat them as rivals," wrote one biographer. 3)

Several works will be shown that reflect the interest of Audubon's era, before and after his own life, in recording, cataloguing, and depicting specimens from nature, including a color wood engraving of a magnolia branch from the rare Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (1743) by Mark Catesby. About Thomas Nuttall, the wide-exploring botanist and ornithologist of whose specimens Audubon copied several, and whose 1834 Manual of the Ornithology of the United States and of Canada is included in this exhibition, Audubon remarked that he was "a gem...after our own heart." 4 Natural scientist James DeKay, who was the editor of the first paper that Audubon presented, compiled the mammoth and well-illustrated Zoological Report of New York State (from 1842), of which a volume on ornithology is included here.

Later nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists Frederick Polydore Nodder, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, and Robert Ridgway, all inspired by Audubon's example, are represented in the exhibition.

John James (né Jean-Jacques Fougère) Audubon was born in Haiti and was reared in France. He emigrated to Pennsylvania at age eighteen. Intrigued by the natural wonders of North America, and inspired to surpass in technical proficiency the work of earlier ornithological illustrators, the self-taught Audubon spent many years of travel and study, as far west as Yellowstone and from Labrador to the Gulf Coast of Texas. Unable to find an engraver and publisher in the U.S. for his drawings and paintings of birds, he succeeded in having a four-volume set published in London between 1827 and 1838, to great acclaim. Subscribers eventually included George IV, and Canada's Parliament.

Audubon's life and career had been plagued by a number of misfortunes, such as failed businesses, losses of his artwork, and, most terribly, losses of children. A rare 1869 edition of Audubon's first biography, edited by his widow Lucy, is included here.

In the years after Audubon entered into his publication agreements in London, and before the publication of the final folio of Birds of America in 1838, he returned to the United States on several occasions to continue his studies of birds and to produce new paintings for the engraving series. His 1831-32 trip to Florida resulted in thirty-one studies, two of which are included in this exhibition: the spectacular Brazilian Caracara Eagle (plate 91), and White-headed eagle (plate 126) 5. Audubon made a visit to Washington prior to the Florida trip - during which he received advice from President Andrew Jackson - and also visited the nation's capital on his tours to find subscribers. (A portrait of the artist by John Syme now is in the White House's collection.)

The late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw a proliferation in the pursuit of knowledge, with landmark achievements in science being among the most important. In the United States, concurrent with the exploration of the North American continent and the growth of cities and towns from coast to coast, there was the gradual establishment of modest schools, colleges, museums, and other centers of learning that eventually would constitute the infrastructure for this increase and preservation of learning.

In the visual arts, many artists devoted their efforts to painstaking study of the natural world. Celebrity landscape painters such as New York's Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt traveled throughout the hemisphere to make accurate studies of topographical features, vegetation, animal specimens, the effects of light, and other phenomena; and to make paintings that were admired for what was presumed to be their fidelity to realism. Artists such as Audubon should be considered in the context of this trend. As Audubon's 1917 biographer Francis Hobart Herrick declared, The Birds of America was "one of the most remarkable and interesting undertakings in the history of literature and science in the nineteenth century. Unique as it was in every detail of its workmanship, it will remain for centuries a shining example of the triumph of human endeavour and of the spirit and will of man." 6 A recent biographer quotes an anonymous reviewer of The Birds of America in the Edinburgh Literary Journal: "Mr. Audubon has done much to silence a set of critics who affect to despise America...Laugh at the young republic, indeed! Where is the state of the old world that can show any results of private and unaided enterprise to stand in competition with what has been effected by three men beyond the Atlantic - Wilson, Charles Bonaparte, and Audubon? The giant is awake." 7

Photography, which became an economically practical tool after Audubon had completed the significant work that defined his career, did not replace the traditional means of reproducing two-dimensional images, but for many artists augmented it. Audubon's work is remarkable in part for the vivid, animated character of many of his subjects, in a time when direct observation of live or dead specimens was the only reliable means for capturing a naturalistic image. "Audubon was not the first to try to portray animals in motion, but his dramatic and vast illustrations of the birds of America were important as attempts to show living creatures." 8

Even as Audubon's achievements in art and science were recognized critically and commercially, his livelihood faced threats from the very interest in and advancement of science that sustained it: As he noted in 1835, "We receive no new subscribers in Europe. The taste is passing for birds like a flitting shadow. Insects, reptiles and fishes are now the rage, and these fly, swim or crawl on pages innumerable in every bookseller's window." 9

The viewer will note that while prints from the original edition of The Birds of America commonly are called "engravings", in fact they were made by a combination of etching methods, including the aquatint etching that facilitated the illusion of gradations of color. 10

The student of Audubon's work must be attentive to the use of nomenclature and spelling in the descriptions of his paintings. In a number of cases, the common names that Audubon used for particular species are not those used today, and some reference works will employ the current names or spellings, which can create some confusion when attempting to match a work with a descriptive entry. (Discrepancies may be due either to changes in convention or, in a number of cases, to identification errors made by Audubon. 11) For this exhibition, we are using the names that Audubon used as they appear on the reproductions of the original etchings.

Indicative of the enduring interest and fascination in Audubon's contribution to the nation's cultural and intellectual history, Audubon's Birds of America: Selections from the "Amsterdam Edition" is on view at Georgetown University concurrent with Audubon's Dream Realized: Selections from The Birds of America at the National Gallery of Art.

1 Robert Brown, "Identifying Audubon bird prints: originals, states, editions, restrikes, and facsimiles and reproductions," in Imprint (Autumn 1996). The viewer will note with interest that six original plates owned by the American Museum of Natural History were restored in 1985 and used to print an edition of 125, in commemoration of the two-hundredth anniversary of Audubon's birth (Duff Hart-Davis, Audubon's Elephant: America's Greatest Naturalist and the Making of The Birds of America (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2004): 273).

2 Some biographers have speculated that Buffon's work likely would have been known in the household of Audubon's French upbringing; see Shirley Streshinsky, Audubon: Life and Art in the American Wilderness (New York: Villard Books, 1993): 15; and John Chancellor, Audubon: A Biography (New York: Viking Press, 1978): 32.

3 Chancellor, 58.

4 Streshinksy, 277; see also Chancellor, 201–03.

5 See Kathryn Hall Proby, Audubon in Florida (Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1974).

6 Quoted in Duff Hart-Davis, Audubon's Elephant: America's Greatest Naturalist and the Making of The Birds of America (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2004): 271.

7 Hart-Davis, 184. Charles Bonaparte was a fellow ornithologist with whom Audubon had had relations of mixed amicability, and is known for such works as A Geographical and Comparative List of the Birds of Europe and North America, and Birds of Mexico.

8 David Knight, The Age of Science: The Scientific World-view in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Basil Blackwell, 1986): 113.

9 Letter to Edward Harris, quoted in Hart-Davis, 226.

10 Brown, 13.

11 Brown, 12.

Above: Brasilian Caracara Eagle, Polyborus vulgaris; Plate CLXI from The Birds of America.

- David C. Alan, Art Technician

Wild Turkey

1/1

Mealagris gallopavo. Linn.

Even the prose of academic biographies sometimes cannot mask the visceral enthusiasm that Audubon's work elicits: "Yet the splendour of his paintings, as produced by Lizars and the Havells, remains stunning: the big birds in particular - the Wild Turkey, the Whooping Crane, the Golden Eagle - take one's breath away. "*

* Duff Hart-Davis, Audubon's Elephant: America's Greatest Naturalist and the Making of The Birds of America (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2004): 271.

White-headed Eagle

CXXVI / 126

Falco leucocephalus, Linn.

"St. Johns River, East Florida, 7th February 1832. - I observed four nests of the White-headed Eagle this day, while the United States' schooner Spark lay at anchor not far from the shore. They were at no great distance from each other, and all placed on tall live pine-trees....As we went nearer, the old ones flew off silently, while the young did not seem to pay the least attention to us, this being a part of the woods where probably no white man had ever before put his foot, and the Eaglets having as yet no experience of the barbarity of the race...."*

* Excerpt from Ornithological Biography, reprinted in Kathryn Hall Proby, Audubon in Florida (Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1974), 135.

Brazilian Caracara Eagle

CLXI / 161

Poluyborus vulgaris, Vieill.

"I was not aware of the existence of the Caracara or Brazilian Eagle in the United States, until my visit to the Floridas in the winter of 1831....Convinced that it was unknown to me, and bent on obtaining it, I followed it nearly a mile, when I saw it sail towards the earth, making for a place where a group of vultures were engaged in devouring a dead horse....The most remarkable difference with respect to habits, between these birds and the American Vultures, is the power which they possess of carrying their prey in their talons...."*

This image, one of the most magnificent in the Georgetown University Library's collection from the Amsterdam Edition, was reprinted in Georgetown, the University's official alumni magazine, in recognition of the generous donation of these prints to the University.

* Excerpt from Ornithological Biography, reprinted in Kathryn Hall Proby, Audubon in Florida (Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1974), 91, 94.

Ornithological Biography, or an account of the habits of the birds of the United States of America...

John James Audubon

Philadelphia: Judah Dobson, Agent...and H. H. Porter..., 1831

Audubon published his Ornithological Biography, or an account of the habits of the birds of the United States of America, in Edinburgh in five volumes between 1831 and 1839. Intended to amplify and accompany his Birds of America, the Ornithological Biography provided detailed observations of the physical properties and characteristics of each species, his reactions to them, and in some cases the best method of capturing or hunting them.

Frustrated by what he saw as his limitations with his adopted language, English, Audubon for a number of years had been seeking in futility for a collaborator for Ornithological Biography. "In his search for a ghost-writer, by another of the amazing strokes of luck which seemed to befall him at critical moments, Audubon almost at once hit upon an ideal collaborator," William MacGillivray, a professor at the University of Edinburgh who was an acquaintance of one of Audubon's scientist friends in that city. "Yet if the arrangement of the text is amateurish, the writing itself, as polished by MacGillivray, was crisp, accurate and easy to read, and it was he who contributed a great many of the scientific and anatomical details. In the words of Elliot Coues, Audubon's 'page is redolent of nature's fragrance; but MacGillivray's are the bone and sinew, the hidden anatomical parts beneath the lovely face.' "*

* Duff Hart-Davis, Audubon's Elephant: America's Greatest Naturalist and the Making of The Birds of America (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2004): 177, 182.

Of those specimens depicted on the two pages open here, the plumage of the beautiful Ivory-billed Woodpecker Audubon compared to the "style and colouring" of the great Baroque painter Anthony Van Dyck. Described in volume 7 of the series, the largest American woodpecker - now extinct - inhabited "the lower parts of the Carolinas, Georgia, Allabama [sic], Louisiana, and Mississippi." Foreshadowing its later demise, Audubon recorded that:

"Travellers of all nations are fond of possessing the upper part of the head and the bill of the male... I have seen entire belts of Indian chiefs closely ornamented with the tufts and bills of this species, and have observed that a great value is frequently put upon them."

An article in the April 2005 issue of the journal Science claimed that the ivory-billed woodpecker had been seen or heard in Arkansas, but this has not been confirmed, to the satisfaction of other ornithologists, by any concrete evidence.

The Amsterdam Edition plate of the magnificent Caracara Eagle, described in volume 4, also is displayed in case S5.

The Life of John James Audubon, the Naturalist.

John James Audubon

Ed. by his widow. With an introduction by Jas. Grant Wilson (New York: G. P. Putnam & Son, 1869)

Audubon and His Journals, Maira Audubon, ed;

with zoological and other notes by Elliott Coues

(orig Charles Scribner's Sons, 1897; this edition New York: Dover Publications, 1960; two vols.)

Maria Audubon, who compiled this indispensable work, was the artist's granddaughter. The last of the "Episodes" in volume two is "My Style of Drawing Birds", in which Audubon wrote, "The better I understood my subjects, the better I became able to represent them in what I hoped were natural positions. The bird once fixed with wires on squares, I studied as a figure before me, its nature, previously known to me as far as habits went, and its general form having been frequently observed." (p. 526)

John James Audubon; William Vogt, intro. and descriptive text. The Birds of America (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1937)

Georgetown University Library

John James Audubon; William Vogt, foreword and descriptive captions. The Birds of America (New York: Macmillan, 1953)

Georgetown University Library

Carlotta J. Owens, John James Audubon: The Birds of America (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1984)

Georgetown University Library

Annette Blaugrund and Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., eds., The Watercolors for The Birds of America (New York: Villard Books/New-York Historical Society, 1993)

John James Audubon: The Birds of America; June 16 and 17, 1983 (New York: Sotheby's, 1983)

American Ornithology: or, The natural history of the birds of the United States:

Alexander Wilson (1766-1813)

illustrated with plates, engraved and colored from original drawings taken from nature.

(Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1808-14)

Georgetown University Library; Special Collections Division

The relationship between Audubon and the Scottish-born writer and illustrator Alexander Wilson has been a source of both historical interest and partisan contention since the years when the two ornithologist's lives and work overlapped, beginning with a fateful meeting on March 18, 1810, in Louisville, where Audubon was engaged as a merchant. They met again in Philadelphia in the summer of 1812.

Of that first meeting: Wilson, who was on a tour to find subscribers for what was to become the nine volumes of his American Ornithology, had learned of Audubon's reputation as an illustrator of birds, and called upon Audubon at his Louisville store. According to accounts, Wilson asked to see Audubon's drawings, and, apparently impressed, inquired if Audubon had plans to publish them. Audubon had not heard of Wilson and his groundbreaking work prior to this meeting, and most chroniclers attribute Audubon's subsequent career motivations to a desire to surpass in quality both the illustrations and the scientific accuracy of Wilson's work. One biographer assessed that "Audubon was a more proficient artist, but Wilson was by far the better writer...." (Streshinsky 631), and Audubon retained a strong interest in Wilson's work during the subsequent years that Wilson's volumes were published posthumously. (For example, Audubon's years as a merchant in Cincinnati were valuable in part for the opportunity to study Wilson's books and specimens in the museum at Cincinnati College.) Also asserted by Audubon biographer Shirley Streshinsky: "Wilson, who became Audubon's nemesis only posthumously, never knew the role he was to play in the younger man's life."(77) "Wilson had become Audubon's lodestar; their two brief meetings had set him on course." (103) Audubon would not consider a recently acquired specimen "to be a new species 'until I see Willson's [sic] 9th Volume.' At that point, Audubon measured everything he did against Wilson." (115)

One dedicated advocate of Wilson's place in history, Clark Hunter, the editor of The Life and Letters of Alexander Wilson, wrote: "When the first volume of [American] Ornithology came out in 1808, it was not the work of an untrained amateur but of a man who had equipped himself for the first scientific description and listing of American birds." (Hunter 4 2) In describing the fateful meeting between Audubon and Wilson, Hunter assessed Audubon as a man "who was to surpass [Wilson] as a bird artist but not as an ornithologist or pioneer." (93)

Whatever "rivalry" there may or may not have been was exacerbated by Audubon's imprudently critical comments about the late Wilson's work during his first appearance before the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, many of whose influential members had been friends and admirers of Audubon's predecessor, and who were in a position to influence Audubon's opportunities for publishing his work (Streshinsky 148-51) "...[T]here was never much personal animosity between [Audubon and Wilson], for after a short illness Wilson died prematurely in 1813, aged only fifty. It was his friend, editor and biographer George Ord who later revived and exploited the feud in his attempts to promote Wilson's work and attack Audubon's." (Hart-Davis, 33 3) As biographer John Chancellor dramatically stated it, "Posterity, encouraged by the partisan accounts of contemporaries, has chosen to treat them as rivals. They take their place in history as antithetical personalities - like Gladstone and Disraeli, Jefferson and Hamilton - each unable to appreciate or to understand the other."4

Audubon had sought a publisher in Britain partly to escape those controversies vis-à-vis Wilson that had hindered his efforts in the United States; but even across the Atlantic, Audubon occasionally was assailed by critics, on grounds of both scientific accuracy and scholarly integrity, one of the most ferocious and persistent of whom being prominent naturalist Charles Waterton (1782-1865): "Without leaving behind him in America any public reputation as a naturalist, Mr Audubon comes to England, and he is immediately pointed out to us as an ornithological luminary of the first magnitude. Strange it is that he, who had been under such a dense cloud of obscurity in his own western latitude, should have broken out so suddenly into such dazzling radiance, the moment he approached our eastern island." (Hart-Davis, 200)

Of the "rivalry" that was sustained by the Audubon and Wilson "factions" for decades after the artists' deaths, Wilson biographer Hunter wondered "[i]f only Audubon had acknowledged what the passage of 150 years would indicate to be Wilson's due - that at the very least he made Audubon's task easier and that the meeting in Louisville was probably the inspiration which led from American Ornithology to The Birds of America." (Hunter, 97)

In assessing Audubon's legacy vis-à-vis Wilson by another standard, one biographer noted that in 2000, a complete set of the original folio of The Birds of America sold at auction for an estimate-doubling $8,802,5000, whereas "a good set of Alexander Wilson's American Ornithology fetches between $12,000 and $14,000." (Hart-Davis, 272)

1 Citations to Shirley Streshinsky are in Audubon: Life and Art in the American Wilderness (New York: Villard Books, 1993)

2 Citations to Clark Hunter are in The Life and Letters of Alexander Wilson, Clark Hunter, ed. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1983)

3 Citations to Duff Hart-Davis are in Audubon's Elephant: America's Greatest Naturalist and the Making of The Birds of America (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2004)

4 John Chancellor, Audubon: A Biography (New York: Viking Press, 1978): 58.

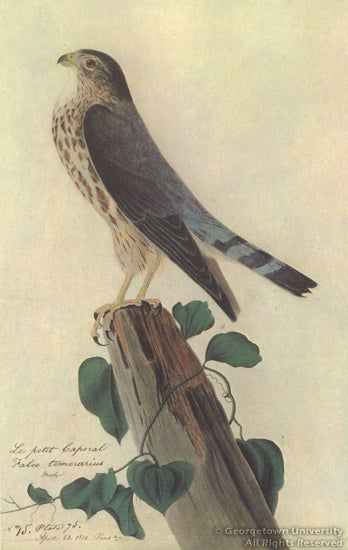

Here we have shown, as a useful comparison, Alexander Wilson's depiction of the Ferruginous Thrush, next to John James Audubon's more dramatic composition.

Magnolia blossom

Mark Catesby (1683-1749)

hand colored engraving, Georgetown University Library, Gift of George Wshington Parke Custis, 1833

The English naturalist Mark Catesby published his groundbreaking Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands in London between 1734 and 1741, following two expeditions to the southern colonies facilitated by the benevolence of native American guides. Catesby systematically collected plant and animal specimens, took detailed notes, and made copious drawings of local flora and fauna. Recognized as the first great publication on American natural history, Catesby's work depicted birds and mammals in their natural surroundings, establishing the precedent for successors such as Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon. Catesby's system of naming species, which recognized inherent relationships between animals and birds, was influential to Linnaeus's system of binomial nomenclature and its application to indigenous American species. On July 4, 1833, George Washington Parke Custis, the step-grandson of George Washington, donated to Georgetown College his family's copy of Catesby's tome. While in America doing research for the History, Catesby had stayed for a time with Custis's great-grandfather, John Custis of Williamsburg, whose name was inscribed on the volume's title page. The book also was owned by George Washington at Mount Vernon before coming ultimately to Georgetown, where it now is housed in the Library's Special Collections Division. This plate illustrating the magnolia flower and foliage was folded in half and inserted unbound into the Natural History. In order to reproduce his original illustrations, Catesby learned to etch his own plates, and supervised the laborious hand-coloring process as well.

Histoire naturelle des oiseaux

Georges Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788), illustrations by Francois Nicolas Martinet (ca. 1731-ca. 1790)

(Paris: De l'Imprimerie Royale, 1770-1786), Georgetown University Library; Special Collections Division

"The great Buffon, who made the study of natural history respectable in aristocratic circles, must certainly have shed some of the rays of his influence upon the unsuspecting head of the young Audubon. His Histoire naturelle des oiseaux...was the most splendid and sumptuous monument of its day to ornithological art, only to be superseded by Audubon's The Birds of America. Buffon's chief illustrator, F. N. Martinet, France's foremost bird painter, foreshadowed Audubon in his dramatic presentation of large species such as hawks, parrots and macaws."1

Also, according to Audubon biographer John Chancellor, it was Audubon's ornithological predecessor Alexander Wilson who was "scandalized by Buffon's theory that American birds were descended from European ancestors who, in crossing to the Western hemisphere by a northern route, had degenerated in the process....Wilson, of the genus irritabile at the best of times, exploded at this affront to his patriotism."2

1 John Chancellor, Audubon: A Biography (New York: Viking Press, 1978): 32.

2 idem, 59-60.

A Manual of the Ornithology of the United States and Canada

Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859)

(Boston: Hillard, Gray and Company, 1834), Georgetown University Library; Special Collections Division

A professor and curator at Harvard University, Nuttall was a valuable and admired acquaintance of Audubon's. From an expedition to the Rocky Mountains and Pacific coast sponsored by the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, Nuttall had numerous specimens not seen or studied by Audubon, about ninety duplicates of which he sold to Audubon and which augmented The Birds of America substantially. (Audubon had been refused permission to study the Academy's specimens due to lingering ill-will over the "rivalry" with Alexander Wilson; see cases W6, S2.) "[Nuttall] sympathized with Audubon in his difficulties with 'the soi-disant friends of science, who objected to my seeing, much less portraying and describing those valuable relics of birds, many of which had not been introduced into our Fauna.' "*

* John Chancellor, Audubon: A Biography (New York: Viking Press, 1978): 202.

Zoology of New-York, or the New-York Fauna...Part II. BIRDS

James E(llsworth) De Kay (1792-1851)

from Natural History of New York (Albany: Carroll and Cook, Printers to the Assembly, 1844), Illustrations by John William Hill (1812-1879), Georgetown University Library

As noted in the exhibition introduction, Portuguese-born James E. De Kay was the editor of the first paper that Audubon presented; this volume of his Zoology of New-York on birds contains bibliographic citations to six of Audubon's works, including The Birds of America and Ornithological Biography. English immigrant illustrator John William Hill , who prepared chromolithographs for the volume, had established his reputation first as a topographical artist, and was an associate of the National Academy of Design.

Bird-life: A Guide to the Study of Our Common Birds

Frank M(ichler) Chapman (1864-1945), Illustrated by Ernest Seton Thompson (1860-1946)

New York, D. Appleton and Company, 1898, Georgetown University Library, Special Collections Division

Born in Englewood, New Jersey, Frank Chapman was a self-taught ornithologist who, in his pursuit of this avocation, eventually became the first curator of the separate Department of Birds at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. He was an original board member of the Audubon Society, and was an advocate on behalf of conservation laws to protect birds. He wrote seventeen books and was the founding editor for the Audubon Society's official publication.*

Illustrator Ernest Seton Thompson (or, in some sources, Ernest Thompson Seton) was a British author and illustrator of nature guides and outdoor life, who worked in Canada and the United States, and who was a founder of the movement that led to the Boy Scouts.

* Anne Becher, American Environmental Leaders, from Colonial Times to the Present, vol. 1: A-K (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2000): 170-72.

White Fronted Owl

"Owl"

Frederick Polydore Nodder (n.d.; active ca. 1770-1800)

engraving with hand coloring

16 x 11 cm.

Plate 171, from vol. ? of George Shaw and F. P. Nodder, The Naturalists' Miscellany; or coloured figures of natural objects drawn and described immediately from nature

Frederick Polydore Nodder was a British watercolorist known primarily for his botanical drawings. He exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1786, and was described in 1788 as "botanical painter to her Majesty".* He converted into paintings drawings from James Cook's voyage to Australia, some originals of which now are in the collection of the British Natural History Museum.**

* The Dictionary of National Biography. The Concise Dictionary, Part 1... (London: Oxford University Press, 1953): 86-87.

**Australian National Botanic Gardens: Biography

Cyanocitta Ultramarina, Var. Arizonae AD.

R(obert) Ridgway (1820-1929)

chromolithograph, printed by T. Sinclair & Son, Philadelphia, 23.3 x 29.5 cm., Georgetown University Library Fine Print Collection

This chromolithograph of the Western scrub-jay, native to Arizona, was drawn by Robert Ridgway, the first curator of ornithology at the U.S. National Museum (now Smithsonian Institution) from 1880 until his death in 1929. Ridgway collected bird specimens while serving as a naturalist on Clarence King's geological survey of the 40th Parallel, a major map-making program in 1867 that stretched from the mountain ranges in Wyoming to the California coastline. Ridgway's expertise attracted the attention of Spencer F. Baird, first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, who assigned Ridgway to his post at the Institution and co-authored several books and journal publications with him, including the multi-volume History of North American Birds - Land Birds (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1874), the most likely source of this loose plate.

Chickadee (Parus Atricapillus)

"Chickadee, Nuthatch"

Louis Agassiz Fuertes (1874-1927)

chromolithograph, 30.3 x 24 cm.

Georgetown University Library Fine Print Collection

White-Breasted Nuthatch (Sitta Carolinensis)

Reproduction. A related illustration was published in Farmers' Bulletin no. 513: Fifty Common Birds of Farm and Orchard (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. Of Agriculture, 1913).

Louis Agassiz Fuertes became fascinated with birds at a young age, and was profoundly inspired by Audubon's illustrations for Birds of America, which he first saw on a visit to the local public library with his father. Agassiz was among the scientists and artists on the 1899 expedition along the Alaskan coast, led by Edward H. Harriman. As with Audubon, he sketched from dead birds, and went on to become the foremost ornithological artist of his time. A variation of this illustration of the chickadee was published in the Farmers' Bulletin 513: Fifty Common Birds of Farm and Orchard (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1913), p. 9.

- Text by Art Collection Curator LuLen Walker, and Art Technician David C. Alan.

The following persons are acknowledged for their contributions to and assistance with Audubon's Birds of America: Selections from the "Amsterdam Edition": Prof. Gary Filerman, Director of the Health Systems Administration Program at Georgetown University's School of Nursing and Health Studies, and Melvin Goldfein were the donors of the "Amsterdam Edition". Assistance was provided by Marty Barringer, Associate University Librarian Emeritus for Special Collections; Karen H. O'Connell, Reference Librarian; and David Hagen, Graphic Artist with the Library's Gelardin New Media Center.