MUSIC IS A LIVING ART, a creative thread that binds together a wide variety of people: from composers and performers to audience members, pedagogues and critics. Archival sources, like the works featured in this exhibition, reveal how behind-the-scenes communication and collaboration facilitate the music-making process. Like all the performing arts, music builds community on multiple levels.

Autograph letter

Joseph Joachim (1831-1907)

17 April [1897?]

Joseph Joachim was one of the most influential violinists of the 19th century. A close friend and collaborator of Mendelssohn, Schumann, Dvořák and Brahms, he offered his opinion about works in progress and later premiered many of their violin masterpieces. The most unusual work written for Joachim was the F-A-E Sonata for piano and violin, composed in 1853 by Brahms, Schumann, and one of Schumann’s students, Albert Dietrich. The title is a reference to Joachim’s favorite saying: “Frei aber einsam” (Free but lonely).

Joachim deeply valued the virtues of civility, which is revealed in this letter to “Mrs. Campbell Clarke,” the wife of an English music critic. Joachim regrets that he will not be able to visit with Mrs. Clarke (and “Rubinstein, the Sympathetic”) while she is staying in Paris. Personal connections like this facilitated the musician’s growing fame in England at the turn of the century. In 1904 the English poet Robert Bridges published a sonnet “To Joseph Joachim” in the London Times (17 May) in celebration of the violinist’s Diamond Jubilee.

Autograph letter

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

undated

Many consider Franz Liszt the greatest piano virtuoso of the 19th century. For the first four decades of his life, he travelled across Europe, astounding audiences with his technical versatility and mesmerizing stage presence. But Liszt was more than a performer. His invention of the Tone-Poem (a single-movement work of loose construction inspired by a literary subject) revolutionized symphonic music. And his dedication to promoting the works of friends and colleagues made him a respected conductor. Committed to the belief that music could be used as a force for good, Liszt worked hard to institute reforms in the church, conservatory and concert hall. He was a tireless teacher who dedicated most of his life and finances to supporting his students.

Liszt wrote countless letters every day. Some were updates to friends and family with long descriptions of his travels and adventures. Others, like this one, were dashed off quickly to colleagues. In this case, Liszt writes:

You must have received the proofs several days ago of:

1) The Italian “Soirées”

2) The 9th, 11th and 12th Etudes

3) The Concert Piece for the poor Italians (on this subject, I should like to remind you that “Papa Ricordi” agreed with me that the price for this piece should be 150 francs).

Liszt then asks that each piece be “carefully corrected” and sent to the appropriate publisher.

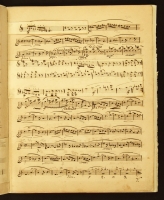

Autograph manuscript of Liszt’s piano transcription of the ballad “Der Asra” by Anton Rubinstein

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Franz Liszt made countless piano transcriptions of music by other composers. Sometimes these transcriptions adhered closely to the original (as in the case of his transcriptions of Beethoven’s symphonies). Other times, as in this piece, the piano version differed markedly from its source. Liszt’s transcriptions were a sign of respect. In each case, he chose works that he found intellectually or sensually appealing. This manuscript, written by a copyist with corrections (in red) by Liszt, reveals the multiple stages of the compositional process.

Manuscript of String Quartet in D, Op. 41

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Like the other music example in this exhibition, this manuscript was prepared by a copyist and then corrected by the composer. The manuscript is not dated, but it was likely completed in 1843 as a final step before publication; the corrections match the final, published version. As one can clearly see by the numerous corrections, some of which are pasted into the score, Schumann was making changes to the quartet right up until the time of publication. These changes were no doubt the result of hearing the work performed by friends and colleagues, the final step in the completion of most compositions.

Autograph postcard

Eduard Hanslick (1825-1904)

2 February 1890

Eduard Hanslick is widely regarded as the founder of modern musical criticism. A prolific writer, he wielded great power during the second half of the 19th century as Vienna’s most formidable music critic. Hanslick studied to be a lawyer, but eventually his interest in music took over. In Vienna he wrote for the Wiener Musik-Zeitung and then the Neue Freie Presse. Hanslick’s book On the Beautiful in Music (1854) transformed the way European society thought about music. He stressed the autonomy of music, and had little patience for Liszt’s Tone-Poems or Wagner’s operas. For Hanslick, the gold standard of music was to be found in the works of Mozart, Beethoven and Brahms (his life-long friend).

In this postcard, Hanslick is sending a friendly reminder to an unnamed acquaintance about borrowing a score (piano reduction) of Hector Berlioz’s comic opera Benedict and Beatrice. Hanslick had mixed feelings about Berlioz’s music. Although he disdained the composer’s use of extra-musical programs, he could not help but admit in his published reviews that Berlioz’s scores revealed “an admirable intellectual coherence.”

Autograph letter

Hans von Bülow (1830-1894)

20 December 1863

Hans von Bülow embodied the ideal of the nineteenth-century musician. Remembered today for his considerable gifts as a conductor, von Bülow was also an acclaimed concert pianist and composer. He began piano studies at age nine with Friedrich Wieck, father and teacher of Clara Wieck-Schumann, and quickly distinguished himself as a concert artist. His association with Franz Liszt (beginning in 1850) was a critical influence in his life and led him to the music of Richard Wagner. During the 1850s and 1860s, von Bülow built his reputation as a concertizing pianist, composer and increasingly as a conductor of challenging contemporary works. The present letter was written shortly before von Bülow was appointed Kapellmeister in Munich. Posted from Berlin in December 1863, von Bülow writes of his arrival in Dresden for a concert and asks his correspondent whether musicians can be arranged to perform Rubinstein’s Piano Quartet. Albeit brief, the letter underlines the itinerant life and multi-faceted skills of a successful musician, and in the case of von Bülow, his emphasis on contemporary repertoire.

Autograph letter

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

3 November 1905

Debussy is often described as the embodiment of musical Impressionism. His distinctive, languid sound was a product of diverse compositional influences, which included native French traditions as well as Mussorgsky and Wagner. The present letter is addressed to an unnamed patron who is seeking a copy of Debussy’s second and only-completed opera Pelléas et Mélisande. Debussy began work on Pelléas in 1893, after abandoning his first opera Rodrigue et Chimène. The completion of Pelléas took nine years, and when it was finally premiered in 1902, reactions were mixed. It was eventually established in French repertory and tallied more than one-hundred performances at the Opéra-Comique in Paris. In this letter, Debussy is responding to a request he received for a copy of the Pelléas score. Debussy’s tone is altogether casual when he notes that he is no longer the owner of the score. Rather Debussy suggests the supplicant should contact the publisher Durand et fils to purchase a copy, underlining the commercial nature of contemporary music publication and even perhaps his own detachment from a work that took so long to complete.

Autograph letter

Ferrucio Busoni (1866-1924)

1 February 1897

Busoni was the consummate musician: a pianist, composer, conductor, pedagogue, essayist and critic. The child of two musicians, Busoni was a prodigy who made his performance debut at age seven. He was deeply influenced by Liszt, Brahms and Anton Rubinstein, all of whom Busoni knew on a personal level. Busoni spent much of his career in transit from one country to the next, often serving in multiple capacities. He made a considerable impact as a concert pianist and conductor, renowned for his ability to perform and interpret contemporary music. Busoni also left a considerable legacy as an essayist. His Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music (1907) is a provocative analysis of the contemporary music environment and prescient advocacy of new approaches to composition. Busoni was also highly successful as a pedagogue, almost single-handedly training a new generation of musicians that shared his progressive ideas, including Kurt Weill, Edgard Varèse, and Luigi Russolo. The present postcard is to his mother Anna, also an accomplished pianist, detailing his frequent engagements in the month of February 1897. Of particular interest is the variety of cities visited in rapid succession (Amsterdam, Utrecht, Arnhem, The Hague, Rotterdam, Vienna, &c.) for concerts. Busoni also notes his correspondence with Hugo Wolf and a mutual colleague Casetti. Ever the good son, Busoni closes the postcard by asking his mother to write “at least a single sentence” to him in Berlin.

Autograph manuscript of Ein Gespräch über Musik

Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894)

Remembered today as a preeminent piano virtuoso and heir to Liszt, Rubinstein was also an accomplished composer, conductor and pedagogue. Rubinstein regularly embarked on international, multi-city tours spanning several years. His performances in Berlin gained the early support of Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer, who helped him establish his reputation in Germany. With the outbreak of the 1848 Revolution, Rubinstein returned to Russia and embarked on a lengthy career as a pedagogue. His dedication to teaching ultimately culminated in his establishment of the St. Petersburg Conservatory, which became the foremost school of music in Russia. Through his teaching, he established a longstanding, intimate relationship with the Czarist Romanoff dynasty. Rubinstein was legendary for his acerbic personality and his clashes with critics and fellow musicians. These qualities are in full view in the featured manuscript, structured as a dialogue between Rubinstein and an unnamed lady. It clearly outlines his thoughts about contemporary music criticism and serves as a rebuttal to those critics who had launched attacks against him in the past. In particular, Rubinstein rejects the claim that he was “not Russian enough” and that his conservatory promoted a specifically “Germanic” approach to the training of musicians.

Curators: Dr Anna Celenza & Dr Anthony DelDonna

Installation: Scott Taylor & John Buchtel, Special Collections

Performance: Vasily Popov, cello and Ralitza Patcheva, piano. Friday Music Series, 18 September 2009

All manuscripts on display are drawn from the Leon Robbin Collection in the Special Collections Research Center.