The Booth Family Center for Special Collections, located in Georgetown University’s Lauinger Library, commemorated the 160th anniversary of District Emancipation with an exhibition of documents that explore the significance of the act that ended slavery at Georgetown College and its surrounding areas. Enacted on April 16, 1862, the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act freed 3,000 individuals bound to labor in the nation’s capital. The act was a major victory for abolitionists, who had campaigned to end slavery and helped advance the cause of civil equality in the only jurisdiction directly governed by Congress.

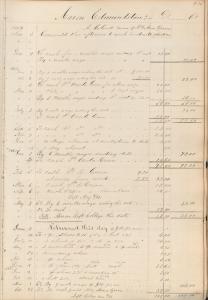

Aaron Edmonson Account, 1859-1862. Georgetown College Accounts Journal G, 1838-1873. (I.A.2.e.)

Aaron Edmonson was the only person working at Georgetown who was freed by the District Compensated Emancipation Act of April 1862. For nearly three years, Georgetown paid his owner Ann Green $12 per month for his “work in the dormitories.” After his emancipation, Ann Green received nearly $40 in back wages from the College and $109.50 as compensation for the loss of her human property. "Civil War Washington," a digital humanities project based at the University of Nebraska, provides a transcript of the petition filed by Ann Green on June 28, 1862, where she requested compensation of $500 for the loss of Aaron Edmonson.

Elizabeth Keckly, Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House

New York: G.W. Carleton & Publishers, 1868.

A formerly enslaved woman and highly-skilled dressmaker, Elizabeth Keckly reveals in this memoir how she earned the trust of First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln. Keckly explains how she used her relationship with the Lincolns to helped build support for the Contraband Relief Association, which she and other Black women established in 1862 to provide food and relief to people escaping slavery. Although Keckly intended to portray Mary Lincoln sympathetically, the revelation of private details of their relationship stirred controversy and fractured their friendship.

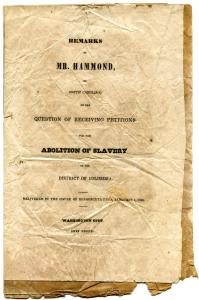

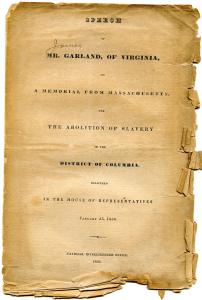

Congressional Speeches Opposing Abolition in the District of Columbia, 1836

“Speech of Mr. [James] Garland of Virginia on a Memorial from Massachusetts, for the Abolition of Slavery in the District of Columbia. Delivered in the House of Representatives, January 26, 1836” National Intelligence Office.

“Remarks of Mr. [James Henry] Hammond, of South Carolina, on the Question of Receiving Petitions for the Abolition of Slavery in the District of Columbia. Delivered in the House of Representatives, February 1, 1836.” Washington City: Duff Green.

The American Anti-Slavery Society organized petition drives demanding that Congress abolish slavery and the slave trade in the District of Columbia. Anticipating thousands of petitions during the 24th Congress (1835-1837), Southern representatives, including James Henry Hammond and James Garland, argued that abolition in any jurisdiction violated the constitutional right to private property and successfully advocated that the House of Representatives establish a gag rule to block the reading of these abolitionist petitions.

“The Lobby of the House of Representatives at Washington during the Passage of the Civil Rights Bill”

Wood engraving

Harper’s Weekly, April 28, 1866.

After emancipation, Black Washingtonians demanded the rights of citizenship and a part in civil life in the national capital. They attended Congressional sessions where Republicans argued for their rights. This illustration of the lobby of the House of Representatives portrayed in the foreground a Black man lobbying for the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Passed after Congress overrode President Andrew Johnson’s veto on April 9, 1866, the Act guaranteed the protection of the law to all U.S. citizens and represented a hallmark achievement of the Republican Congress.