What is an emblem? While nearly forgotten today, the emblem was the paradigmatic genre from the 16th to the 18th century, and most commonly consisted of three elements: a motto (a title, phrase, proverb, or quote from biblical or ancient sources), a picture (usually highly symbolic), and a description (often in verse). Used both in schools and for private study, emblems were meant to invite the viewer to ponder how an idea or relationship found in the natural, moral, or political spheres, might be found, analogically, within another relationship. For example, a drawing of an ant, depending on the appended motto and verse, might illustrate such varying themes as the virtue of personal industry, the superiority of monarchical government, the strength found in collective action, or the spiritual growth gained through steady labor.

While sometimes didactic and easily decoded, emblems could also be deeply enigmatic, with motto and picture in tension with each other, and no easily discernible moral or explanation. Emblems such as these, were often used as parlor games, and showcased the malleability of the genre, with the ability to generate wildly speculative and creative associations.

The authority of the emblem rested not in a particular argument, but in a Christian-Platonic worldview that assumed that all of reality is symbolic, with all phenomena subsisting in, and finally revealing, the eternal structures of a universe ordered towards God. Unsurprisingly, Jesuits, drawn to both spiritual meditation and pedagogical technique, were deeply involved in the creation and use of emblems and included emblem composition in their curriculum, the Ratio Studiorum. However, the genre was popular with Catholic and Protestant alike, with thousands of emblem books printed at the height of its popularity.

By the end of the 18th century, the influence of the emblem was in steep decline as the worldview in which it was founded was increasingly challenged by an empiricist epistemology deeply suspicious of non-mechanistic explanation and appeals to authority. Emblems were seen as simplistic, in a world that was anything but simple. Recently, however, the emblem has been the subject of renewed interest and retrieval, as scholars have rediscovered their creative possibilities.

Emblemata denuo

Considered one of the first emblem books, if not the first, Alciati’s Emblemata, coined the word emblem in connection with the genre, and formed its chief elements in 1531. Consisting of a combination of a motto, picture, and verse, Alciati’s emblems drew upon natural phenomena, ancient history, and biblical texts to illustrate moral, political, and religious values. For the next two centuries, the Emblemeta would be endlessly reprinted, translated, copied, and commented upon.

Pia desideria emblematis

The Pia Desideria (Pious Desires) by the Flemish Jesuit, Herman Hugo, S.J. (1588-1629), is perhaps the most published and influential emblem book after Alciati’s Emblemata. Drawing from his experience with Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises, Hugo put his emblems to a decidedly more spiritual use, with each emblem serving as an opportunity to contemplate the soul’s differing relations to God. In the emblem shown, the angel hides her face, providing an opportunity for an extended exploration on the subtleties of divine hiddenness.

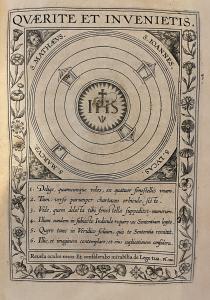

Veridicvs Christianvs & Occasio arrepta, neglecta, huius commoda, illius incommoda

Jan David, S.J. (1546–1613), rector of Jesuit colleges in Ghent and Courtrai, produced a series of incredibly popular emblem books as pedagogical tools for catechumens. Veridicus Christianus (The True Christian) and Occasio Arrepta, Neglecta (Occasion Seized, Shirked), illustrate pathways to virtue, and the necessity to seize opportunities for spiritual growth. The Veridicus Christianus also contains a very interesting device (page shown), a moveable wheel called “the wheel of probity,” meant to facilitate further contemplation of the emblems. The wheel, when turned, provides a number that corresponds to a list of maxims taken from authors of antiquity. The catechumen is then meant to find the emblem that best corresponds to the chosen maxim.

Lux evangelica sub velum sacrorum emblematum

Belgian Jesuit, Henricus Engelgrave, S.J. (1610-1870), produced 52 emblems on the holy days, feast days, and feast days of the year, with accompanying sermons. The page shown, is a meditation on avoiding the opportunity to sin “lest we run into present danger like a gnat circling a lamp.”

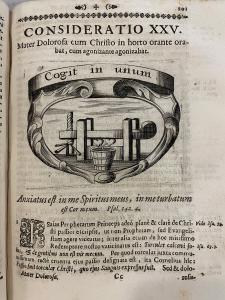

Mater amoris et doloris

Mater Amoris et Doloris, by Antonius Ginther, is a collection of 70 emblems each containing symbols that pertain to the Blessed Virgin Mary. The work attests to the variety of ways emblems served to contemplate religious themes, with Mary being a particularly popular subject of Catholic emblem books.

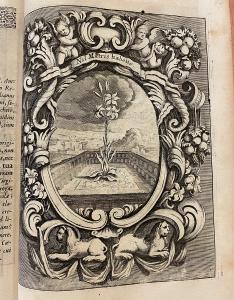

Innocentia vindicata

Celestino Sfondrati (1644-1696), a Benedictine theologian from Milan, published this work on the Immaculate Conception. Each emblem draws the connection between natural phenomena (in the example shown, a pure white lily grows from the dirtiest mud) and the sinlessness of Mary.

Micae panis caelestis

Just as Sfrondati’s work explored the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception through emblems, Wenceslaus Schwerfer, S.J., used the genre to consider different theological aspects of the Eucharist. Shown here, the emblem depicts the Eucharist as providing a safe passage to eternity, avoiding the roads to hell and purgatory.

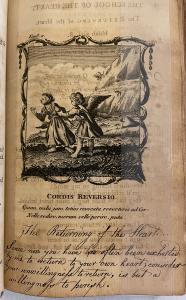

The School of the Heart

In the same vein as Herman Hugo’s Pia Desideria, Harvey’s The School of the Heart was explicitly “Designed to present us with the anatomy of the human heart in a moral or spiritual view, to expose its disorders, their nature, and their cure.” This was a common theme among religious emblems and hearkens back to such popular devotional work as Thomas a Kempis’ The Imitation of Christ.

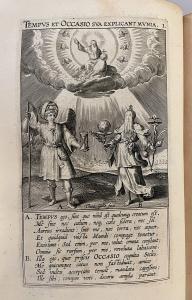

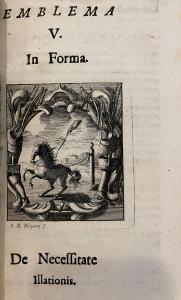

Emblemata philosophico-moralia

Caspar Mandl, S.J. (1655-1728) wrote the Emblemata Philosophico-Moralia, as the title suggests, as a series of emblems on philosophical and moral themes. In the page shown, the emblem depicts the relationship of the eternal forms to temporal reality, demonstrating the power of emblems to aid in conceptual understanding.

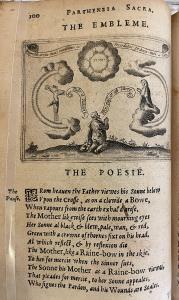

Parthenia Sacra

A series of 48 emblems by Henry Hawkins, S.J. (1571?-1646) an English Jesuit. Hawkins emblem book, a devotional work, is unique in that it includes commentary on different aspects of the symbol, with sections titled: The Character, The Morals, The Essay, The Discourse, The Poesie, The Theories, and The Apostrophe.

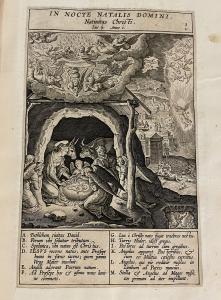

Adnotationes et meditationes in Euangelia

While not strictly an emblem book, Geronimo Nadal’s Adnotationes et Meditationes is often lumped in with the genre, as it depicts gospel scenes presented for the purpose of contemplation. Just like emblems, each scene includes a key, with different aspects given a corresponding letter and description. A meditation on each aspect follows, with an extended elaboration meant to aid the viewer in visualizing each moment.

Curated by Adrian Vaagenes, Woodstock Librarian