See also the companion exhibition, Margaret Bonds: Composer and Activist. The Margaret Bonds Papers (GTM 130530) are available to researchers in the Booth Family Center for Special Collections.

Introduction

Toward the end of her life, Margaret Bonds (1913-1972) reflected on the day she discovered the poetry of Langston Hughes (1902-1967). It was in 1929, her first year as a music student at Northwestern University:

I was in this prejudiced university, this terribly prejudiced place…. I was looking in the basement of the Evanston Public Library where they had the poetry. I came in contact with this wonderful poem, "The Negro Speaks of Rivers," and I'm sure it helped my feelings of security. Because in that poem he tells how great the black man is. And if I had any misgivings, which I would have to have – here you are in a setup where the restaurants won't serve you and you’re going to college, you’re sacrificing, trying to get through school – and I know that poem helped save me.

Hughes wrote "The Negro Speaks of Rivers" in 1920 while traveling on a train from Cleveland to Mexico. It was published one year later in the literary journal Crisis, and again in 1926 as part of his first poetry collection The Weary Blues. This was the book Bonds discovered. Its musical title spoke to her right away, and over the next four decades she and Hughes forged an artistic bond based on mutual respect, genuine affection and a shared enthusiasm for new creative challenges. This exhibition tracks the course of their musical friendship and the enduring legacy of their artistic collaborations.

Ten years would pass before Bonds and Hughes came face-to-face. "I actually met him," explained Bonds, "after I came out of the university." The encounter took place at the home of a mutual friend, an artist named Tony Hill. Shortly thereafter, Hughes attended one of the Sunday afternoon musicales hosted by Bonds's mother, Estella. “My family rolled out the red carpet,” claimed Bonds. And from that day forward, "we were like brother and sister, like blood relatives."

Items in the Exhibition:

1

Bonds began to set Hughes’s poems to music in 1936. In addition to “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” she composed “Joy,” “Love’s Runnin’ Riot,” “Park Bench,” “Poème d’Automne” and “Winter Moon.” Although Hughes moved to New York later that year, he kept in touch with Bonds and encouraged her activities as a composer and performer. This is clearly revealed in the telegram he sent to her on April 23, 1939. Knowing that she was nervous about an upcoming recital, he wrote: “I can hear you playing way over here and it sounds good.”

- Margaret Bonds Publicity Photo (1956), taken by Carl Van Vechten.

- Telegram from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds, dated April 23, 1939.

- Langston Hughes Publicity Photo (1959).

2

In 1938, Bonds founded the Allied Arts Academy in Chicago. She also collaborated with Hughes on the musical Don’t You Want to be Free?. Due to economic difficulties, the Allied Arts Academy closed in 1939. In an effort to lift Bonds’s spirits, Hughes encouraged her to move to New York, which she did in August 1939. In New York, Bonds found work as an editor at the Clarence Williams publishing company. She also began playing piano at the Apollo Theater. These new ventures renewed her interest in writing popular songs – an activity Hughes encouraged, as revealed in his correspondence.

Hughes took Bonds under his wing when she moved to New York and introduced her to his wide circle of friends and colleagues. One of these friends, a parole officer named Lawrence Richardson, had been a student with Hughes at Lincoln University. Richardson and Bonds tied the knot in 1940, but domestic life did not slow her down. Shortly after the marriage, she collaborated with Hughes on another musical, Tropics After Dark.

- Margaret Bonds, Typescript of Lyrics to “Bound” and “If You’re Not There” (ca. 1940). Bonds composed these songs as a wedding gift to her husband Lawrence Richardson.

- Letter from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds dated August 6, 1942.

3

When Bonds published “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in 1942, she dedicated it to Marian Anderson. Bonds had hoped that Anderson would premiere the song, but she did not like its “jazzy augmented chords.” So the honor went instead to Etta Moten, the singer for whom Gershwin originally composed the role of “Bess” in Porgy and Bess.

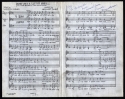

Both Bonds and Hughes worked hard promoting “Rivers,” and in an effort to have it performed as frequently as possible, Bonds created various choral settings of the song. On May 25, 1941 a male chorus performed such a setting at Town Hall in New York.

- Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes, SATB setting of “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” (1962).

- Letter from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds, dated October 10, 1942.

4

Hughes was constantly sending Bonds lyrics he hoped she might set to music. Some were serious in nature, others, like “When a Bluebird Lost Its Feather,” more light-hearted.

In 1940, when the writer Arna Bontemps was appointed cultural director of the state-sponsored American Negro Exposition in Chicago, he contacted Hughes and asked him to collaborate on a new musical revue titled Tropics After Dark. Excited about the project, Hughes asked Bonds to write some of the music, and for several months he and Bontemps mailed her lyric sheets with suggestions concerning the mood and style of the music they envisioned. But the project never came to fruition. Corrupt politics and a mismanagement of funds by the city left both Hughes and Bonds without a contract or payment. After consulting lawyers, Hughes gave up all plans of suing. “I think a gangster would have more success collecting our money than a lawyer,” he claimed, “and would probably ask no higher percentage.”

- Lyrics for two songs from Tropics after Dark (1940): “Lonely Little Maiden by the Sea” and “Pretty Flower of the Tropics.”

- Letter from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds with lyrics by Hughes for a new song titled “When a Bluebird Lost Its Feather” (ca. 1942).

5

Bonds and Hughes continued their collaborations during World War II, and their efforts were praised by the U.S. State Department. As the only African American on the Writers’ War Committee, Hughes wrote numerous songs to support the troops. Through letters, he kept Bonds up-to-date on his work and occasionally sent her copies of the songs he was writing with others. In 1941, Hughes produced a radio broadcast for CBS titled Jubilee: A Cavalcade of the Negro Theatre. This work, originally written several years earlier for the American Negro Exposition in Chicago, featured a wide array of music. The broadcast was so popular that Hughes was asked by the War Department to revive it in 1943 “for the fighting men overseas.”

- Langston Hughes, Typescript of Lyrics for “That Eagle of the U.S.A.” – a song composed by Hughes and composer Emerson Harper in 1943.

- Letter from Colonel Livingston Watrous of the U.S. War Department to Margaret Bonds, dated March 23, 1943.

6

Hughes sent Bonds and her husband autographed copies of each book he published. For Bonds, these gifts were especially meaningful, and the poems inside often inspired new compositions, as can be seen in the notes she added to several of the poems in Field of Wonder.

- Langston Hughes, Field of Wonder (1947), signed by the author to Margaret Bonds and Lawrence Richardson.

- Interior pages of Field of Wonder with comments by Margaret Bonds concerning a song cycle she hoped to compose based on Hughes’s poems.

- Margaret Bonds, “Heaven,” Autograph manuscript of a song based on Hughes’s poem.

7

In 1954, Bonds and Hughes began working on what would prove to be their most successful collaboration, a Christmas cantata titled The Ballad of the Brown King. An early version of the work was premiered by the George McClain Chorale (with Bonds at the piano) on December 12, 1954 at the East Side House in New York, a non-profit social services organization where Bonds taught music. After the premiere, Bonds and Hughes set to work revising the piece and promoting it to various performance venues. The enlarged, orchestrated version was dedicated to Martin Luther King, Jr. and first performed on December 11, 1960 at the Clark Street YWCA. This version, conducted by Bonds, was also televised by CBS as part of a program titled Christmas U.S.A. One song from The Ballad of the Brown King, “Mary Had a Little Baby,” proved so popular that it was published for solo voice in 1962.

- Letter from Margaret Bonds advertising a repeat performance of The Ballad of the Brown King and sent to various church pastors in New York, dated December 17, 1954.

- Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes, Revised libretto for The Ballad of the Brown King with comments and corrections added by Bonds, dated Aug 26, 1955.

- Letter from Warner Lawson (Dean, Howard University) to Margaret Bonds, dated October 3, 1955.

- Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes, Autograph score of “That was a Christmas Long Ago” from The Ballad of the Brown King (1954).

8

- Promotional Flyer for The Ballad of the Brown King at the Clark Street YWCA(1960).

- Tickets for The Ballad of the Brown King at the Clark Street YWCA(1960).

- Letter from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds, dated November 11, 1960.

- Programs for The Ballad of the Brown King performances in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago.

- Letter from Anne Lincoln (White House Social Secretary) to Margaret Bonds, dated September 11, 1962.

- Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes, “Mary Had a Little Baby” from The Ballad of the Brown King (Fox Music Publishing, 1962).

9

Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes, Autograph manuscript of full orchestration for “Could He Have Been an Ethiope?” from The Ballad of the Brown King (1960).

10

Throughout the 1950s, Bonds and Hughes increased their efforts to draw attention to African-American writers and musicians. Bonds remained active as a performer, and her modern settings of traditional spirituals became especially popular among young, African-American singers.

- Program for Music and Poetry of the Negro, a benefit event for Everybody’s Art Center in Newark, N.J. (December 12, 1952).

- Promotional Flyer for “A Program of Music, Poetry and Song” featuring Margaret Bonds, Langston Hughes and Gregory Simms.

- Program for Laurence Watson’s voice recital at Town Hall in New York (March 25, 1956).

11

As the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum, Margaret Bonds became a tireless promoter of African-American artists. In addition to sponsoring concerts and curating exhibitions featuring the works of black composers and poets, she founded The Margaret Bonds Chamber Music Society, which was dedicated to establishing a canon of art music by African-American composers. Bonds believed it was her duty as a composer and educator to serve as a bridge between the artists of the past and those of the future.

- Program for “Music of the Negro Composer” presented by the Margaret Bonds Chamber Music Society (October 28, 1956).

- Margaret Bonds, Description of songs she composed using texts by Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen. This description appeared in various choral concerts conducted by George McClain in the mid-1950s.

- Draft of a letter in a music notebook, from Margaret Bonds to the leadership at Mt. Calvary Baptist Church, wherein she describes her philosophy of teaching with regards to music and African-American culture (ca. 1966).

12

- Program and ticket for “A Tribute to Langston Hughes” (April 27, 1958), organized by Margaret Bonds. Postcard and thank you letter from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds, dated April 21 & 28, 1958.

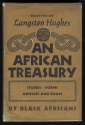

- Langston Hughes, An African Treasury (1960), signed by the author to Margaret Bonds and Lawrence Richardson.

- Postcard from Langston Hughes to Lawrence Richardson, dated April 10, 1958. “Simple” refers to Jesse B. Semple, a popular “Everyman” character that appeared in Hughes’s fiction.

13

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, Bonds continued to set Hughes’s texts to music. In addition to composing two song cycles, Songs of the Seasons and Three Dream Portraits, she composed the incidental music for Shakespeare in Harlem (1960), a theatrical adaptation of the poetry collection he published in 1942.

- Press release featuring positive reviews for a 1955 performance in Texas of Shakespeare in Harlem.

- Program for Shakespeare in Harlem at the 41st Street Theater, New York (February 1960).

- Postcards from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds discussing Shakespeare in Harlem, dated February 10 & 12, 1960.

14

Bonds and Hughes put a great deal of effort into promoting Shakespeare in Harlem. Although the production received glowing praise from critics, attendance dropped off soon after the premiere, which Bonds found extremely frustrating. Nonetheless, she and Hughes continued on, brainstorming future projects and writing new songs.

- Promotional flyer advertising Shakespeare in Harlem (1960).

- Letter from Margaret Bonds to her Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority sisters, dated February 15, 1960, encouraging them to attend Shakespeare in Harlem.

- Letter from Margaret Bonds to Langston Hughes, dated March 29, 1960. The letter is written on the back of a Shakespeare in Harlem promotion flyer.

15

After Shakespeare in Harlem closed, Bonds and Hughes collaborated on several songs, including “Note on Commercial Theatre,” “When the Dove Enters In” and “Sing Aho.”

- Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes, “Note on Commercial Theatre,” complete manuscript draft, dating from January 1961. This is the only known copy of this song. Prior to this exhibition, scholars believed this work was either lost or never completed.

16

In her correspondence with Hughes, Bonds often opened up to him about her struggles with depression and her frustration with the music industry. She also shared news about other African-American artists, such as her close friend, the opera singer Charlotte Holloman. In his letters and postcards, Hughes attempted to lift Bonds’s spirits, and he continued to encourage her efforts as a composer and cultural activist.

- Letter from Margaret Bonds to Langston Hughes dated February 16, 1960.

- Valentine card from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds (ca. 1960s).

- Invitation for a Program of Songs by Negro Composers, featuring the song cycle Three Dream Portraits by Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes, at the Sculpture Court of the Brooklyn Museum on February 21, 1960.

- Letter from Margaret Bonds to Langston Hughes dated September 28, 1960.

17

In 1962, Bonds was asked to speak at a conference titled The Executive Woman at Fairleigh Dickinson University. In her letters to Hughes, she shared news of such honors in addition to updates about the publication of their collaborative works.

- Program for The Executive Woman conference held at Fairleigh Dickinson University on March 24, 1962.

- Letter from Margaret Bonds to Langston Hughes, dated March 27, 1962. At the end of the letter, Bonds concludes with a musical motto and the words: “Nina’s gonna have a little baby…But I hope she records Mary’s baby first!” This is a reference to Nina Simone, who was in talks at the time with Fox Publishers about recording “Mary Had a Little Baby” from Ballad of the Brown King.

- Letter from Bob Bollard at Belafonte Enterprises to Margaret Bonds, dated October 31, 1962.

- Postcard from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds, dated May 25, 1962. The “Baby” referred to here is “Mary Had a Little Baby” from The Ballad of the Brown King.

- Langston Hughes, Lyrics to “When the Dove Enters In.”

- Certificate of copyright for “When the Dove Enters In,” dated September 3, 1963.

18

In discussions of the working relationship between Bonds and Hughes, great attention is generally given to the poet’s influence on the composer. Although their friendship began with Bonds playing the role of an avid fan and admirer, the influence and inspiration flowed in both directions over their 40 years of collaboration. Both cherished that “Something in Common” they found in music, and in works like “Ask Your Mama” and the Song-Play Jerico-Jim Crow, Hughes revealed his indebtedness to Bonds’s friendship and guidance.

- Langston Hughes, Something in Common (1963), signed by the author to Margaret Bonds and Lawrence Richardson.

- Invitation from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds for the first live reading by Hughes of Ask Your Mama: 12 Moods for Jazz (February 6, 1961). Hughes began writing the cycle of poems in 1960, when he witnessed a group of white youths rioting because they could not get tickets to the Newport Jazz Festival.

- Flyer for a performance of Langston Hughes’s Jerico-Jim Crow, with a personal note from Hughes to Margaret Bonds (early 1964). Hughes wrote the lyrics and music for this work, which offers a history of the African-American experience. The title of the show comes from its theme: the endless fight to knock down the walls of Jim Crow, who appears in the play again and again, first as a slave trader, then as a policeman and as a white Southerner chanting “Better Leave Segregation Alone.”

- Langston Hughes, “Freedom Land” from Jerico – Jim Crow (Ralph Satz Publications, 1964).

19

After the success of the Christmas cantata The Ballad of the Brown King, Bonds was inspired to compose an Easter cantata, Simon Bore the Cross, again in collaboration with Hughes. The friends worked on the composition for several years, and as their correspondence reveals, their progress was often delayed due to other projects and commitments. Although a complete draft of the cantata was finished in late 1964, it was never premiered. And prior to this exhibition, scholars believed that the first four movements were lost. Georgetown University owns the only complete score of Simon Bore the Cross.

- Postcard from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds, dated February 24, 1963.

- Letter from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds, dated March 25, 1963.

20

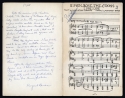

Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes, autograph manuscript of the SATB choral arrangement of “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” prepared by Bonds especially for the Lincoln University Glee Club and dated September 13, 1963.

21

Piano prelude to Simon Bore the Cross. Autograph manuscript of the only known complete draft of Simon Bore the Cross,accompanied by a note by Margaret Bonds, dated January 31, 1964, describing the composition’s genesis.

22

Bonds and Hughes never stopped collaborating on compositions, and they worked equally hard on programming events designed to promote African-American music and poetry. Although their collaborations ended with Hughes’s death in 1967, Bonds never gave up on the projects they had started. But the loss of her friend and collaborator was hard on Bonds, and in an effort to overcome increasing bouts of depression, she sought a change of scene in Los Angeles, where she tried her hand at writing for film. Bonds outlived Hughes by five years, and during those years she kept the memory of her friend alive. In Los Angeles, she began organizing her papers, many of which she hoped to donate to the Langston Hughes Memorial Library at Lincoln University.

- Letter from Langston Hughes to Margaret Bonds, dated January 27, 1964. Here Hughes offers advice about revising the layout for an upcoming concert promoting African-American music and poetry.

- Letter from Margaret Bonds to Langston Hughes dated August 8, 1965. Bonds updates her friend on her most recent projects and asks if he “wants to write a show.”

23

- Telegram from the Family of Langston Hughes to Lawrence Richardson and Margaret Bonds, dated May 23, 1967.

- Program for the Memorial Service of Langston Hughes.

Exhibition curated by Anna Celenza, Thomas E. Caesteker Professor of Music