Of the war itself I have little to add. It is over and, like one's schooldays,

neatly defined by its dates. I served in ten ships, the largest

a 20,000-ton armed merchant cruiser in the South Atlantic...

Operations at different times took me as far south as the Antarctic

and as far north as Russia.

--Michael Richey, from the preface of Sailing Alone

Michael Richey (1917-2009), first director of the Royal Institute of Navigation (UK) in 1947 and founding editor of its prestigious Journal of Navigation in 1948, served in the Royal Navy throughout the whole of the Second World War, most of it at sea in the North Atlantic. For one extensive interlude he was in the South Atlantic. From there, as we read in the epigraph, he went really South—nearly as far south as polar explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton and his team—for a secret expedition on HMS Carnarvon Castle, the ship on which he served as Assistant Navigator (RNVR) between 1942-43 under Captain Edward Wollaston Kitson. This was Richey’s fifth ship, following a stint in the Free French Navy on the corvette, F. S. Roselys. Based in Freetown, Sierra Leone, they were offshore for significant stretches, with average trips at sea lasting a month or more.

By the end of the war, Richey had completed his specialist course at the shore-based Navigation School, HMS Dryad, and was appointed Navigator of ships involved in the D-Day landings at Normandy and the U-boat surrenders at Loch Eriboll. But what of his passage? How did he get there? What do we actually know of his wartime travels and what records of this did he leave, given censorship during wartime, the secrecy of positions, and the erratic nature of postal deliveries at sea?

Thanks first to the conservationist efforts of his mother Adelaide, and subsequently Georgetown University Library’s manuscripts librarian Nicholas Scheetz, there is now a considerable Richey archive lodged in the Booth Family Center for Special Collections, as part of its collections on British Catholic authors. After attending the Catholic boarding school Downside in Somerset, Richey had seriously considered a monastic vocation before going to artist Eric Gill’s printing press and lettering workshop at Pigotts in Buckinghamshire, where he apprenticed as a stone carver and letter cutter from 1936 to 1939. This highly formative period led to lifelong friendships with a literary and artistic circle that included Tom Burns, Harman Grisewood, René Hague, and David Jones, all of whom are also represented in the manuscript collections at Georgetown.

During the war, Richey wrote some first-rate letters from various ships and naval bases (as did his brother Paul, author of the classic book Fighter Pilot, A Personal Record of the Campaign in France, 1939-1940, first published anonymously, due to regulations at the time, in September 1941 by B. T. Batsford, and subsequently by Scribners three months later, in an edition which featured the author's name and a cover photograph by Cecil Beaton). Michael Richey also wrote superb first-hand accounts of two events: the sinking of his first ship HMS Goodwill and the expedition of HMS Carnarvon Castle. The first, “Sunk by a Mine,” having been refused by the British naval censors “on the grounds that it might ‘lower morale,’” was published overseas in The New York Times Magazine on May 11, 1941; it won him the first John Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize for Literature in 1942. The second, “A Taste of the Antarctic,” was written as a broadcast and read by (Sir) Ludovic Kennedy for the BBC. Kennedy became a well-known broadcaster after the war, and this was his first broadcast.

Post-war, Michael Richey became a legend for his singlehanded transatlantic sailing adventures in his famous little boat, Jester, which he bought in 1964 from Herbert “Blondie” Hasler, wartime hero and inventor of the first practical self-steering gear for yachts. He had signature postcards printed for his solo voyages: on the front, a black-and-white photograph of himself sailing the boat; on the back, the incomplete address in black type, “Yacht Jester at ______.”.

This centenary exhibition is a snapshot of one of the most distinguished British navigators of the twentieth century, and one of its most reluctant autobiographers. The epigraph has been taken from an unfinished work, Sailing Alone. The title was suggested to him by his great friend, the novelist Graham Greene, whose centenary Richey celebrated at Georgetown in 2004.

NOTE: Exhibition object titles refer to case placement in the physical exhibition.

W1/1/1

Crucifix. 1917 wood engraving printed in gold on black paper by Eric Gill (1882-1940), after a window at York Minster.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

W1/1/2

A two-page letter dated 11 July 1917, written from the trenches in World War I by Col. George Henry Mills Richey and addressed to "My own adorable wife." Adelaide Titus had come to England from Australia, travelling with a wealthy aunt when she met George. They married in London in 1915. In the letter, George reacts to news of the birth of their second son: "What luck having another boy!" Born on 6 July 1917, and according to his birth certificate, they would fully name him Michael Dugdale William Mills Richey. Their first son Paul Henry Mills Richey was born on 7 May 1916.

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W1/2/1

Photograph of a young and beautiful Adelaide Titus Richey, mother of Paul and Michael Richey, inscribed, "Ever your friend, Addie."

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

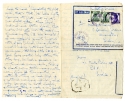

W1/2/2

Envelope for letter sent by George Richey to his wife Adelaide Titus Richey. The address of 9 Chiswick Place, Eastbourne, is where Michael Richey was born on 6 July. Two official stamps indicate the letter was sent from a "Field Post Office 15 July 1917" and "Passed Field Censor."

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W1/3/1

Letter from Michael Richey to "Dear Daddy" dated 20 September from Cheddar in Somerset, England following "an awfully rough trip from France" on a "fearfully big two propelered [sic] boat." "I am longing to (go to) Albania," he writes. Col. Richey was the Assistant Inspector General of the Albanian Gendarmarie (1925-29).

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W1/3/2

Letter dating from Switzerland, 1928 from young Michael Richey to his parents. The Richey brothers were away from home for the first time. He describes life at their new boarding school. "… three or four boys have Girls including us, but that does not mean we will lose a speck of love for you two. On Saturday, lessons finish at 11..."

In the annotations to his letters at Georgetown, Richey writes, "When my father left Albania my parents went to live in Monaco and my brother Paul and I were sent to school at Institut Fisher in Territet Lac Leman in Switzerland." A fellow pupil was Peggy Bolton, daughter of playwright and musical comedy writer Guy Bolton, goddaughter of P. G. Wodehouse, who remained a lifelong friend.

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W1/3/3a

A loose page from a family photo album during the years that the Richey family lived in Monaco. The images show Paul and Michael Richey visiting H.M.S. Warspite in Villefranche. Photo on right: famous tennis champion W.T. Tilden with the two brothers.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

W1/3/3b

Letter from Michael Richey to his parents during the war recalling his visit to the same ship as a child. "A short while ago I had dinner on board a certain ship we went over as kids at Villefranche – Do you remember. There was a photo of Paul and I (Sam & me) on the forecastle with a matelot, that someone has somewhere." The letter is annotated briefly in pencil for a broadcast in 1943 which has been made anonymous in light of wartime censorship. It is headed, "Letter from the South Seas: A Sailor Writes Home."

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W2/1/1

Pre-war photograph (photocopy) of Paul Richey (left) and Michael Richey (right), Downside, the Benedictine boarding school in Somerset, England.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

W2/1/2

Letter from Michael Richey to his parents dated 13 October 1938. "I have got a terrific idea of going to sea at the moment," he writes. The letter is written while he is at Pigotts, working for Gill. It is the first reference to what would ultimately be his vocation: a mariner and navigator.

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W2/2/1

Letter from Paul Richey on the letterhead of the Royal Air Force in Sussex to his family, dated 9 September 1939, at the outbreak of World War II.

Paul Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W2/2/2

Portrait of Michael Richey as an ordinary seaman in the 1940s, before the sinking of his first ship, H.M.S. Goodwill and his commissioning as an officer.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

W2/3/1

Postcard to Michael Richey from Tom Burns dated 16 March 1940, from the Museo Del Prado of the San Miguel Arcángel. Burns wrote: "Dearest Mike, this seems to be a v. Good picture v. your own. I do hope you're alright. It's incredible here." The postcard was re-addressed three times before it reached Richey.

After the war, Burns served as editor of The Tablet, a Catholic weekly. It was Burns who later introduced Richey to Graham Greene.

Jimmy Burns, former journalist for the Financial Times, wrote this riveting biography of his father’s wartime service in Spain. Tom Burns's papers are also held by Georgetown. Richey attended the launch of Papa Spy in September 2009, just months before his sudden death on 22 December, aged 92.

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W2/3/2

The last page of an early letter from Michael Richey to his family written in 1940 from his first ship, the minesweeper H.M.S. Goodwill. As a post-script he writes: "A note on death: I feel that, apart from the common mission of all chaps of being ultimately united to God which is not affected by being killed, I probably have some sort of job to accomplish in this odd world ... so that if I am killed prematurely, it will mean I have no 'big' thing to do in that way--in wh. case it won't matter." He adds: "for your consolation. Actually I think I have a thing." He went on to survive three shipwrecks, including the sinking of Goodwill, and two capsizes in his boat Jester (1986; 1988).

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W3/1/1

Letter (pages 7-8) from Paul Richey to Michael Richey written on Mike's 23rd birthday, 6 July 1940. Recovering at the home of his in-laws in Devon from injuries sustained in the Battle of France (for his extraordinary service he received the DFC on his return to the UK), Paul writes, "The secret, if any, of successful air-fighting is the use of such contradictory qualities as dash, judgment, daring, precaution, ferocity, + coolness, not of course all at once (!), but at the correct times, in the correct sequence ... Some day I'll write a book about it if I survive! If I don't, of course, it won't matter because my theories must be wrong!"

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

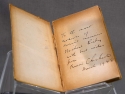

W3/1/2

The book Fighter Pilot was first published anonymously in 1941. Subsequent editions have included the name of the author, Paul Richey. Shown: this revised 1955 edition published by Hutchinson & Co. LTD is inscribed and signed by Paul Richey, "To Lord Douglas with some wonderful memories of my service under him in Fighter Command in 1941 & 1942. New Year's Day, 1956."

The most recent edition of Fighter Pilot, edited by Diana Richey, widow of Paul Richey (1916-1989), was published by The History Press in 2016, during his centenary.

Loan from the Nicholas B. Scheetz Charitable Trust

W3/2/1

Letter from Michael Richey aboard H.M.S. Goodwill to his parents dated 24 August 1940. There is a missing photograph referred to in the letter, of a sweeper blowing up a mine. Several letters in his collection remark on censorship during wartime: "Don't send it to a paper or anything as it won't get passed because of showing the ship--though God knows why you shouldn't show the ship."

He is just getting to know life at sea. "It's a rum thing sea life really. Sometimes you think it's the ports you want to visit, & sometimes it's the life & work in ships that you like & sometimes that it's the easiest way to live without being tied down."

Several of his letters have classic sign-offs. "I'd like some oranges. Love from Mike."

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W3/2/2

Letter to Michael Richey from his mother Adelaide, 27 June 1940: "Dad by the way is in khaki again and has an office of his own, and commands a company of two platoons." His father had a long and distinguished military career.

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W3/3/1

Letter from Michael Richey to his parents from H.M.S. Goodwill (c. December 1940; written on the back of a sheet of paper printed "Naval Message"). Richey refers to Captain [Louis] "Ricci" (who later anglicized his name to ‘Lewis Ritchie’ in a 10 April 1946 letter also shown in this exhibition). “Ricci/Ritchie” was a retired naval paymaster and was instrumental in getting Michael Richey into the Royal Naval Patrol Reserve. It was Tom Burns who introduced them at the Ministry of Information.

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W3/3/2

Letter from Michael Richey to Harman Grisewood dated 19 December 1940, referring to his account of the wreck of H. M. S. Goodwill. "I couldn't set it in a true focus without reflecting on the general nature of the whole war."

Richey has elsewhere recorded that so far as he could remember, he wrote the story in a single sitting in Farleigh Wallop, as a guest at the home of Lord Lymington (the 9th Earl of Portsmouth), whilst on survivor’s leave.

The story won the first Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize for Literature in 1942.

Harman Grisewood papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W4/1/1

Michael Richey, wood engraving, c.1938-39. Christmas card printed by Hague & Gill. In Richey’s writing, quotes appear from Moby Dick on the cover, and from John Donne on the inside of the card.

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

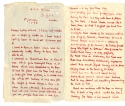

W4/2/1

Original autograph manuscript of Michael Richey's story ‘Sunk by a Mine’ with corrections, 1940.

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W4/2/2

Letter from Michael Richey to his parents written from the H.M.S. Glen Avon, dated 23 April 1941. His mother has addressed a letter to him, in the process inadvertently revealing his position. He reminds her that their locations are top secret! "I had a bit of explaining to do." He writes of the blitz, and of learning navigation, taking lessons on board his current ship from a master mariner.

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W4/3/1

Newspaper clipping of “Sunk by a Mine” by Michael Richey, printed in The New York Times Magazine (11 May 1941).

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W5/1/1

Telegram sent to Sub-Lieutenant Michael Richey RNVR H.M.S. Carnarvon Castle, from his father, dated 4 July 1942: "BEST LOVE BIRTHDAY GREETINGS FROM ALL CONGRATULATIONS ON WINNING LLEWLLYN RHYS PRIZE ALL FRIENDS DELIGHTED CHEQUE THIRTY POUNDS WOULD APPRECIATE WIRE = DAD +."

In a preface written expressly for the limited edition printed by Nicholas B. Scheetz on the occasion of Richey’s 90th birthday, Richey writes:

"The subsequent award of the first John Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize came straight out of the blue. The news came by cable from my parents to my ship at the time which was then in the South Atlantic Ocean. I had not heard of the Award let alone being in the running for it. So far as I could reconstruct the sequence of events my parents, in the author’s absence, had submitted my brother Paul’s by then classic book on the air battle of France, Fighter Pilot, for this new award and took the opportunity of submitting my own more modest account of Goodwill’s fate at the same time.

The Llewellyn Rhys Prize was initiated in 1942 by Jane Oliver to commemorate her husband, John Llewellyn Rhys, a young author who was killed in the war."

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W5/1/2

Letter to Michael Richey from the literary agents A.M. Heath & Company dated 27 July 1942, congratulating him on the prize, and asking him to confirm his mother's authority to act on his behalf.

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W5/2/1

Letter from Paul Richey to his parents dated on Richey’s 25th birthday, 6 July 1942. "I’m awfully glad Mike’s got the prize," he writes. "I must say I thought mine might win because of my subject. But I’m much more pleased he won it than if I had myself, quite apart from the merits of his work. I sent him a cable on Saturday."

There is a reference to "Page" towards the end of the letter. This is Page Huidekoper, now Page Wilson, author of Carnage and Courage: A Memoir of FDR, the Kennedys, and World War II (2015). The book includes an account of her time with the Richey family at 68 Cadogan Square while she was in London, working for Ambassador Joseph Kennedy. She remained lifelong friends with the Richeys. A longtime resident of Georgetown, she hosted Michael Richey in 2009, on the occasion of the David Jones event and exhibition.

Paul Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W5/2/2

Log book/diary written by Paul Richey, travelling by sea between England and India via Cape Town in 1942. Both brothers were then on Union-Castle ships and nominally in the same part of the ocean, but in letters to his parents at the time Paul says that he and Mike will unfortunately not meet, that Mike’s ship has apparently gone to Belfast.

Paul Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W5/3/1

Aerogram from Paul Richey to his mother. Note stamp from unit censor in India.

Paul Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

W5/3/2

Portrait of the Richey men: Michael Richey, second to left, with brothers Paul (left), George (right), and father George (middle). Paul and Michael had four half-siblings from their father’s first marriage: George, Freda and the twins Jack and Jill. Their sister Freda was a founding member of the Carmelite Monastery at Dolgellau, Wales.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E1/1/1

Letter written by Michael Richey to his parents dated 22 April 1942. He has just arrived by plane, courtesy of his brother Paul, to join his new ship, H.M.S. Carnarvon Castle. At Catterick, the first person he ran into was his great friend René Hague. He is optimistic about the ship and its captain At 23,000 tons, H. M. S. Carnarvon Castle was absolutely luxurious (a converted Union-Castle liner) in contrast to the corvette F. S. Roselys he had just served in as British Naval Liaison Officer in the Free French Navy.

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E1/1/2

Photocopy of three rare images from a secret expedition to the Antarctic taken by H. M. S. Carnarvon Castle in February-March 1943. On the back of one of the small photographs, he has written that they are near the coast of "Grahams Land."

Michael Richey Collection, Brighton, England

E1/2/1

Typescript from BBC broadcast of "A Taste of the Antarctic." In his brief preface for the limited edition printed by Nicholas B. Scheetz on the occasion of Richey’s 80th birthday, Richey writes:

"In 1943, 'HMS Carnarvon Castle,' a 20,000-ton armed merchant cruiser of which I was at the time assistant navigator, was ordered from her normal patrol area in the South Atlantic (10 degrees N. to 10 degrees S.) to the Falkland Islands. The purpose of the mission was to re-affirm the British claim to the Falkland Islands Dependencies and to make sure that none of them was being used to refuel German warships. This piece was written as a broadcast and in the event read for the BBC by (later Sir) Ludovic Kennedy who after the war became well known as a broadcaster. This was his first.

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E1/2/2

Letter to Michael Richey from Sir Ludovic Kennedy dated 16 November 1998 thanking Richey for "that charming little book" (noted above - a small-press publication of Richey’s story, "A Taste of the Antarctic"). Recalling his BBC broadcast decades earlier of Richey’s same story, Kennedy writes, "You are quite right in thinking my first broadcast was that thing you wrote." Kennedy also congratulates Richey on his solo voyage at age 80 from Newport, Rhode Island to Plymouth, "which fully deserves being recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records."

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E1/3/1

Letter from Michael Richey to Paul Richey, written in December 1943, describing his trip to the Antarctic. Landing on Deception Island, Richey writes, "We planted a Union Jack there, tore down an Argentine flag & buried a document saying the place was bloody well ours. I suppose the Argentines have now sent another expedition."

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E1/3/2

Photograph: Hoisting the Union Jack on Deception Island.

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E2/1/1

David Jones engraving titled "He Frees the Waters in Helyon." Inscribed "for Mick -1944 Aug. from Dai." One of Jones’s favorite engravings, this had pride of place in Richey’s home. It also travelled for exhibitions, including a Jones exhibition at the National Museum of Wales.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E2/2/1

Transcription from a letter from David Jones to "Arthur." In the postscript, Jones writes, "Sometime I'll tell you about Michael Richey..." Jones goes on to tell Arthur all about his friend Mike, providing a perfect mini-biography. "These chaps who love being in a tiny craft and all alone for weeks in crossing oceans must have some quality in them that is special." Having first met him at Pigotts, when Richey arrived to apprentice Eric Gill, Jones notes what a talented stone carver and letter cutter he became, but writes, "one never imagined he would become a first rate navigator in the Royal Navy with all the ability in mathematics that implies."

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E2/2/2

Letter (in French) dated 2 May 1945 from Jacques Maritain, the French Ambassador to the Vatican. He remembered having met Richey previously, and writes that he would welcome seeing him again.

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E2/3/1 and E2/3/2

Letter dated 4 January 1945 from Michael Richey to his parents. He was serving on H.M.S. Pelican. On leave in Rome he went to Midnight Mass which was – quite extraordinarily – celebrated by the Pope on Christmas Eve. This had not occurred since the 11th or 12th century, Richey writes. Additionally, Richey says that he had "an audience with the Pope on Boxing Day & quite a long chat," and that he "(a)sked him for a blessing for [his sister] Freda & her convent."

Letter from Michael Richey to his parents dated 25 June 1945. He was serving on H.M.S. Philante, headquarters ship for accepting U/Boat surrenders.

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E2/3/3

Letter to Michael Richey from Lewis Ritchie (formerly Louis Ricci) dated 10 April 1946. He suggests that a possible post-war position for Richey would be "a job on the Times." He agrees that "the war was too long. But we are still alive and there is a wind on the heath, even though some of us have to put on a muffler to enjoy it." (Sir) Lewis Ritchie became King George VI’s Press Secretary, and accompanied the Royal Family on the tour of South Africa in 1947.

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E3/1/1

Engraving by Michael Richey of a ship c.1938-39, inscribed to Mabel, dated 1947.

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E3/2/1

Book by Francis Chichester on astro-navigation inscribed in 1948 "To the most modern of ancient mariners Michael Richey."

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E3/2/2

First edition (1948) of Graham Greene’s The Heart of the Matter, inscribed: "For Michael Richey affectionately, from Graham Greene in memory of your hold-up at Victoria." This is quite a story, involving a blunderbuss (or a pistol – the story varies), a green cape, a stranger at Victoria Station, and a fortuitous chance encounter with Graham Greene on board the Brighton Belle.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E3/3/1

Sailing instructions, 1965 Fastnet Race, Royal Ocean Club.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E3/3/2

NAVIGATION NOTEBOOK. Richey’s logbook includes several journeys, from his ocean-racing days on Figaro and other yachts in the 1950s, and his early days of single-handed sailing on Jester from the mid-late 1960s.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E3/3/3

Photograph of Michael Richey taking a sextant reading on an ocean-racing voyage, c. 1957.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E4/1/1

Editorial corrections to The Geometrical Seaman, by E.G.R. Taylor and M.W. Richey (Hollis & Carter, 1962). Features the Arctic tern logo Richey designed for the (Royal) Institute of Navigation.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E4/1/2

The Geometrical Seaman. Quote from Bernard Le Boyer de Fontelle, 1699: "The Art of Navigation hath a necessary connection with Astronomy."

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E4/2/1

Profile of Michael Richey, "Catholic View of Observer Race," by Joanna Kilmartin. In the concluding paragraph, Richey translates Baudelaire: “The only real travelers are those who depart for the sake of departing." But as Richey says, Baudelaire "got it the wrong way around. It is the landfall which makes it all worthwhile."

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E4/2/2

Postcard Michael Richey had printed featuring a black & white photograph of him on board Jester; on the back in black ink it reads: "Yacht Jester at ____." Richey would then fill in the port, and write and address cards to his friends. In this card sent to Harman Grisewood, Richey writes from Portugal that he heard a mass sung by nuns "in some song that sounds as though it's been there forever."

Harman Grisewood papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E4/3/1

Typed Introduction written by Prince Philip on Buckingham Palace letterhead for the 21st anniversary issue of The Journal of the Institute of Navigation.

Michael Richey papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E4/3/2

Special anniversary issue of The Journal of the Institute of Navigation (later renamed the Journal of Navigation, Michael Richey was its founding editor in 1948, a position that he held into his retirement until 1985). The cover features a photograph of Jester, and the special issue also features Richey’s article of his first single-handed transatlantic race in Jester from Plymouth-Newport in 1968.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E5/1/1

Photograph of Michael Richey receiving the Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of Navigation in 1979. He was the Institute’s first Director (originally Executive Secretary) from its formation in 1947 until his retirement in 1982.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E5/2/1

Copy of a letter from Graham Greene to Michael Richey dated 20 December 1979. He writes, "I like the address on your notepaper, 'Yacht Jester at blank.'"

The originals of Greene’s correspondence to Richey were auctioned and sold to the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin. Proceeds from the sale were invariably used to re-fit Jester.

The originals of Richey’s correspondence to Greene are held at the Burns Library, Boston College. This collection is not complete, since the early decades of letters Richey would have written are missing – their friendship goes back to a first meeting in 1940; they reportedly only met up again in 1954 after the war and remained lifelong friends.

Michael Richey papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E5/2/2

Letter from M.W. Richey to Harman Grisewood dated 15 May 1985 on his Royal Institute of Navigation/Brighton/Jester stationery. The letter refers to their friends René Hague and David Jones, and to a particular painting by Jones of a ship – knowing how accurate Jones was about all things nautical. See also Richey’s article, "David Jones and the Art of Seafaring."

Harman Grisewood papers 2, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library

E5/3/1

Engraving of "Jonah & the Whale" by Ken Thompson, inscribed to Michael Richey in July 1995. Thompson lives near Cork on Ballycotton Bay, near Shanagarry, where the Hagues had moved from Pigotts; he was at school at Downside too with Richey’s nephews (Paul’s sons), Peter and Simon. Richey considered him one of the finest stone carvers and letter cutters of his generation. Indeed, Thompson carved a headstone for the two brothers. It reads: "Paul Richey (1916-1989): 'Fighter Pilot'" and underneath, "Michael Richey (1917-2009): 'Mariner.'" It has been placed next to their parents’ headstone at the Catholic cemetery, St Mary, Kensal Green, in London.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E5/3/2

Photograph of Captain David Boon of the Dutch ship Geest Bay which rescued Michael Richey – and Jester, in a storm off the Scilly Isles in 1986. This was Richey’s second shipwreck, the third resulting in the rescue of Richey but the loss of Jester in July 1988. Richey has written accounts of both stories in Yachting Monthly. In 1992 at Brighton Marina, a new Jester was launched, a Trust having been formed to build a replica. It was in this boat that Richey sailed across the Atlantic, single-handed, aged 80.

Michael Richey collection, Brighton, England

E5/3/3

Crucifix made by Captain David Boon from the mast of Jester, presented to Michael Richey several years after the rescue. In accordance with a bequest by Richey, the cross was presented after Richey's death (22 December 2009) by Kai Easton to his friend Nicholas B. Scheetz (1952-2016), a former manuscripts librarian at Georgetown University. It was Scheetz who was responsible for securing the Richey archives for Georgetown Library’s Special Collections.

Loan from the Estate of Nicholas B. Scheetz

Curated by Kai Easton, Senior Lecturer in English at SOAS, University of London.

This exhibition is dedicated to Nicholas B. Scheetz, whose foresight and genuine friendship made this event possible.

Diana Pearson and Nick's Georgetown University Library colleagues have generously carried the mantle, offering expert help and support. Thanks to: John Buchtel, Stephanie Hughes, Ted Jackson, Lisette Matano, and Scott Taylor.

And our deepest gratitude to Michael Richey's family and friends, especially: Sabina Bailey, Jimmy Burns, Joe Davis, Pauline Fausset, Charlotte Johnson, Rosalind Ledingham, Sonia (Melchett) Sinclair, Kerena Mond, Sarah Price, Diana Richey, Emma Richey, Peter Richey, Simon Richey, Ken Thompson, Rachel Thompson, and Page Wilson.