On March 11, 2020, the University announced that it was moving to a virtual learning environment as of Monday, March 16, due to the coronavirus pandemic. This was followed by a March 18 announcement that Georgetown was postponing commencement activities to a time in which we can safely convene as a community. In the interim, a virtual celebration of the Class of 2020 was held on May 16. From a survey of records in the University Archives, it appears that on no other occasion since Georgetown College’s first commencement ceremony in 1817 has the University postponed or cancelled a commencement. Even in 1861, when campus had been occupied by federal troops during May and June, a commencement ceremony took place on July 2, even if it was held with no audience and lasted less than twenty minutes. However, the fact that commencements were held does not mean that classes have always continued on campus without threat of interruption. This exhibition highlights some other instances in the University’s history when the continuation of classes was threatened by either internal or external circumstances. It also reveals the University’s reaction to those threats.

Note: The title of this exhibition (No more pencils, no more books) is taken from a line in a school children's rhyme which can be traced back at least to the 1890s. It was famously incorporated into the lyrics of School's Out, a 1972 song first recorded as the title track single of Alice Cooper's fifth album and written by the Alice Cooper band.

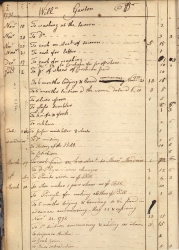

Arrival of Georgetown’s first student in 1791 (William Gaston’s financial accounts, 1791-1792)

While technically a delay to the beginning of instruction on campus, rather than an interruption to ongoing instruction, it is worth noting in the context of this exhibition that our first student, William “Billy” Gaston, arrived in 1791 to begin classes before any dorm or classroom space was ready for him. Billy traveled to Georgetown at the age of 13 from New Bern, North Carolina. His father, a doctor, was killed during the Revolution, so arrangements for his education fell to his mother. He first arrived in spring 1791. Georgetown was not yet open for students, so he went on to Philadelphia. When he returned in November, the only building on campus was still not ready for habitation and he moved into a nearby inn for almost two months. This is reflected in the opening entry of his accounts: November 10, 1791: To washing at tavern 2 [shillings]. Classes began on campus in January 1792.

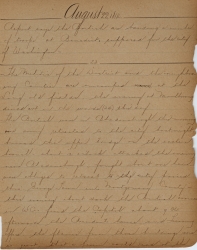

War of 1812 (Diary of John McElroy, S.J., August 22-24, 1814)

When the British broke through the defenses of Washington City on August 24, 1814, Georgetown faculty and the students who had stayed on campus over the summer watched events unfold from the top floor of Old North. As Fr. McElroy wrote in his diary, the glow from the many burning buildings was so great it was possible to read by it that night on campus. Many local residents fled, fearing that the town of Georgetown would be the next target of the British; some stopped at the College to leave valuables for safekeeping. Georgetown University President John Grassi, S.J. decided not to evacuate, although as a precaution he had all articles of silver plate hidden. On August 26, he learned that the British had left, and he resumed preparations for the start of the school year on September 1.

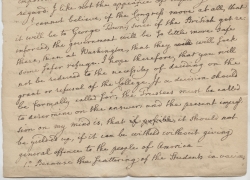

War of 1812 ( Letter from Georgetown’s founder Archbishop John Carroll to Georgetown President John Grassi, S.J., September 30, 1814. Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus)

Classes began on September 1 but it was unclear at that point whether the school year could proceed. The threat to campus was now not from the British; rather it was from the Federal Government. Old North was the largest undamaged structure in the area and the concern was that campus might be co-opted as a temporary seat of government. President Grassi consulted Archbishop Carroll in Baltimore over this possibility. The Archbishop replied in his letter of September 30, 1814: I cannot believe if the Congress move at all that it will be to George Town; since if the British get reinforced, the government will be so little more safe there than at Washington, that they will seek some safer refuge. I hope therefore that you will not be reduced to the necessity of deciding on the grant or refusal of the College. If a decision should be formally called for, the Trustees must be called to determine on the answer and the present impression on my mind is that it should not be yielded up if it can be withheld without giving general offense to the people of America. He further advised on the second page of the letter that if resisting was impossible students should be sent home, as boarding them off-campus would mean a destruction of the excellent discipline now established … and render impractical the same attention to their moral conduct.

In early October, the government of Georgetown (Georgetown had a separate municipal government until 1871) authorized the mayor to offer Georgetown College as an interim capital, having ascertained according to one newspaper account that the trustees would cheerfully give it up. In reality, it appears that Grassi and the trustees could see no alternative and were resigned, not cheerful. Fortunately, John Carroll was proved correct and the offer was not acted on. Given Georgetown’s perilous financial situation at this time, it is unlikely the College would have been able to reopen, had it closed to temporarily accommodate Congress.

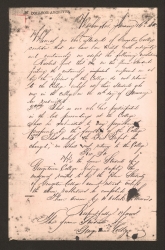

Rebellion of 1850 (Resolutions of the students who left campus, January 16, 1850)

Washington, January 16, '50

Whereas, we the former students of Georgetown College consider that we have been treated with indignity and contumely, we adopt the following resolutions:

Resolved first that we the former students feeling the contumely imposed on us by the officers of the College, do not return to the College unless all those students who were in the College on the 14th day of January be readmitted.

Secondly. That no one who has participated in the late proceedings at the College shall be submitted to any punishment proposed by the faculty of the College.

Thirdly. That unless the First Prefect be changed, we shall not return to the College.

Rev Sir

Whereas the former student s of Georgetown College feeling deeply the measures resorted to by the former students of Georgetown College cannot retract unless the above resolutions by complied with.

Please answer by 11 o'clock tomorrow.

Respectfully yours.

The former students of Georgetown College

In January 1850, while University President James Ryder, S.J., was away, the Philodemic Society sought permission to hold a meeting after studies on a Sunday evening. Permission was refused but the Society went ahead with the meeting regardless. As a result, the First Prefect, Father Burchard Villiger, suspended Philodemic meetings for a month and deprived members of late study privileges. There were mass protests in the dorms and refectory against these punishments, leading to the expulsion of three students on January 15. In response, about sixty other students (out of a student body totaling 180) decamped to the Globe Hotel in Washington and issued an ultimatum that they would not return until they had amnesty and the expelled students were taken back. Georgetown College administrators responded by giving notice to the hotel that the students' bills would not be paid by the College. The students were persuaded to capitulate, demands mainly unmet, and return to campus on January 21.

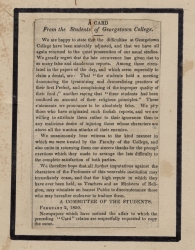

Rebellion of 1850 (Card From the Students of Georgetown College, February 2, 1850)

We are happy to state that the difficulties at Georgetown College have been amicably adjusted, and that we have all again returned to the quiet prosecution of our usual studies . . .

The exact circumstances around the creation of this card are not recorded in the University Archives. The document states on its face that local newspapers - which had reported on the students’ departure and prolonged absence from campus in a light that was not universally flattering to the College - are respectfully requested to print its text. It is possible that its circulation was part of the agreement reached between the students and the College administration to allow the students to return to campus.

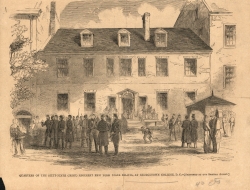

Civil War (Illustration showing the 69th Regiment of the New York State Militia in the Quadrangle, Harper’s Weekly, June 1, 1861)

Georgetown’s campus was occupied three times by Federal troops during the Civil War. However, the College remained open throughout the conflict, despite a severe drop in enrollment. At the beginning of the 1861-1862 academic year, there were only seventeen students enrolled; in contrast, the beginning of the previous academic year found 286 students on campus. The resultant decrease in tuition revenue had a significant impact on College finances. These were so depleted by July 1862 that Georgetown was not able to buy the silver medals traditionally awarded for academic excellence at commencement. Instead, it fabricated them by melting down silver spoons belonging to students who had left.

The first occupation was in May 1861, when the Secretary of War sent the 69th Regiment of the New York State Militia (known as the Irish Regiment) to be billeted on campus. Around 1400 strong, they stayed a month and President Abraham Lincoln visited to review them. Some students had burned an effigy of President-elect Lincoln in February 1861 and the arrival of the 69th was probably a direct result of that. The College was given less than 24 hours notice of the 69th’s arrival and the 60 or so students who still remained (the others having been withdrawn by their anxious parents) had to quickly move out of the buildings on the south side of the Quadrangle (Gervase Hall, Isaac Hawkins Hall, the South Building and Maguire Hall.) These were turned over to the Regiment and College operations contracted into Old North.

The 69th moved west to join forces in Virginia after 3 weeks and on June 4, 1861 were replaced by the 79th New York (known as the Highland regiment) who stayed for a month.

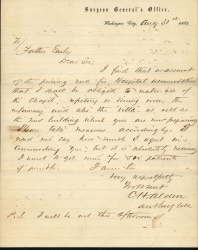

Civil War (Letter to Georgetown President John Early, S.J., from the Surgeon General’s office, requisitioning campus buildings, August 31, 1862. Rev. John Early, S.J. Papers)

The final and only extended occupation of campus began on August 31, 1862, after the 2nd Battle of Bull Run, with the requisition of College buildings because of the pressing need for Hospital accommodation. Old North was not included in the requisition order, apparently due to the intervention of Union General A. W. Whipple, who had 2 sons enrolled in the College. Because of this, Georgetown was able to remain in operation, although campus was not returned to Georgetown's control until February 1863.

Measles outbreak, 1873-1874 (Infirmary Garden with the original lamp placed by the St. Joseph’s Lamp Association seen in front of the statue of St. Joseph, pictured ca. 1905)

In 1872, a garden was created on the south side of campus, bordered by Gervase Hall to the west and Isaac Hawkins Hall and the South Building to the north. This came to be known as the Infirmary Garden because of its proximity to Gervase which housed the campus infirmary at that time. The appearance and size of the garden site changed over time but one constant element was the statue of St. Joseph. At a June 10, 1872 ceremony, the statue was blessed by John McElroy, S.J., in the presence of members of the Jesuit Community, the student body, and invited guests. Fr. McElroy, in his concluding prayer, placed the College and the infirmary in particular under the especial patronage and protection of St. Joseph.

In the fall of 1872, Washington, D.C. saw a serious outbreak of an illness which some records in the University Archives identify as measles (others describe it as a smallpox-like illness). Only one Georgetown student contracted the disease and he survived. The disease returned in the spring but only a few students showed symptoms. During this time, students began the practice of burning a lamp in front of the St. Joseph statue to show gratitude for protection from illness. Eventually, the senior class founded the St. Joseph Lamp Association to pay for lamp oil and ensure that the lamp was kept burning day and night during the prevalence of any epidemic, during the two examinations, and at night during the year.

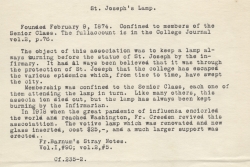

Measles outbreak, 1873-1874 (Fr. Francis Barnum’s "Stray Notes" on St. Joseph’s Lamp, ca. 1919)

The St. Joseph’s Lamp Association appears to have become defunct by the early 1890s but, as these notes written by Francis Barnum, S.J. indicate, it was revived by Georgetown President John Creeden, S.J., in 1918 during the Spanish Flu epidemic. The notes also show that the lamp had been kept burning by the campus Infirmarian, even when the Association was inactive.

Additional notes by Fr. Barnum explain that the original lamp of the Association was not suitable for hanging out of doors. Every rain and windstorm would extinguish it. In March 1919, I [Fr. Barnum] went to Baltimore and purchased a regular ship’s lantern for $12.50 which would burn through any gale or snowstorm. I got the support made at the iron works near the bridge on Pennsylvania Ave. Since then we are always sure the lamp is burning.

Records in the Archives do not indicate at what point the practice of burning the lamp ceased.

Coronavirus pandemic, 2020 ("The St. Joseph Lantern Society placed a lantern by our wonderful St. Joseph statue on Library Walk." Tweet from Georgetown University Police Department, April 15, 2020)

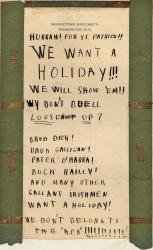

St. Patrick’s Day walk-out, 1908 (Sign protesting the refusal of President David H. Buel, S.J. to declare St. Patrick's Day a holiday, March 17, 1908)

On March 16, 1908, the senior class president requested that the next day, St. Patrick’s Day, be declared a student holiday, with classes suspended. President Buel did not act on the request. After morning Mass on the 17th, 127 students donned green ties and sashes and marched through the front gates, posting this notice as they left.

President Buel, whose name is mentioned in the 5th line of the handbill but is misspelled (it should have only one “l”, though it is unclear whether the misspelling was deliberate) reacted by requiring that all the boarders who participated in the walk-out had to ask him for permission to leave campus for the rest of the year - permission which he denied in every case.

Note that the last line on the handbill references the A.P.A. which was the American Protective Organization, an anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant group founded in 1887.

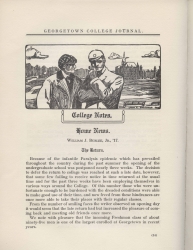

Polio outbreak, 1916 (Georgetown College Journal, October 1916)

The start of the 1916 fall semester was postponed for almost 3 weeks by a polio outbreak. As this article in our student newspaper, the Georgetown College Journal, notes, the decision to delay classes was made so late that some students didn’t know about it and came to campus anyway. This is a good reminder of how, before email or the telephone were ubiquitous, fast communication to groups was challenging.

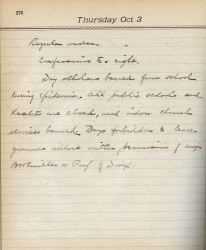

Spanish flu,1918 (Diary entry written by the Prefect of Discipline, October 3, 1918)

All public schools and theaters are closed and indoor church services banned. Boys forbidden to leave grounds without written permission . . .

In 1918, the Prefect of Discipline (Vice President of Student Affairs would be the comparable position today) was Fr. Vincent McDonough for whom McDonough Gym is named. His entries through October 1918 relate to the class schedules, sporting events, and the weather. But in October and early November 1918, the impact of the Spanish Flu on campus dominate the pages of this diary.

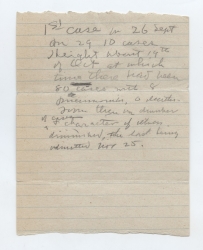

Spanish flu, 1918 (Insert in the House Diary of the Georgetown Jesuit Community, October 1918)

This charts the relatively fast-moving course of the illness on campus:

1st case on 26 Sept

On [Sept.] 29 10 cases

Height about 19th of Oct at which time there had been about 80 cases with 8 [pneumonias?], 0 deaths.

From there on number of cases and character of illness diminished, the last being admitted Nov 25.

Georgetown students were treated at the old Georgetown University Hospital at Prospect, 35th and N Streets, as well as in the on-campus infirmary in the Gervase Building.

Spanish flu, 1918 (Letter from the Executive Committee of the Law School to the University President, outlining how class time lost during the pandemic would be made up, December 16, 1918)

The Law and Medical Schools, both off campus, were closed for a month by the DC health commissioner. Their Christmas vacation was shortened and spring semester lengthened to make up for this. The College was able to continue classes for students living on campus because it was providing military instruction for a War Department program. But there was a guard at the front gate and all visitors had to show a health certificate.

D.C. Riots, 1968 (Notice from the Office of the President: To all the Members of the Georgetown Family, April 5, 1968)

This notice, addressed to faculty, staff, and students, was circulated the day after Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination. Following the assassination, there were 4 days of riots in Washington, D.C. Riots also affected at least 110 U.S. cities; Washington, along with Chicago and Baltimore, were among the locations most impacted. Not all students remained on campus as President Gerard J. Campbell requested. After a memorial service held in the Quadrangle at noon on April 5, a delegation of hundreds of Georgetown students marched to the White House to deliver a petition in support of declaring a national day of mourning for Dr. King.

Students staffed a collection center just off-campus at Holy Trinity School, gathering food, clothing and bedding for those whose homes had been destroyed. Some, including Bill Clinton, signed up with the Red Cross to help deliver food and blankets to other centers. Georgetown's Easter recess should have begun after the end of classes on Wednesday April 10. But all classes were cancelled beginning Monday April 8, allowing students to go home three days early if they wished – many stayed, however, to continue helping local residents.

D.C. Riots, 1968 (Description of the Law Center's volunteer efforts in the Academic Vice President’s newsletter, July 3, 1968)

At the Law Center, just blocks from the spreading disorder, classes were dismissed on April 5. Administrators, faculty and around 200 students went to D.C.'s Court of General Sessions in response to a request from court officials for assistance processing those arrested during the rioting. The Dean of the Law School helped coordinate the many attorneys who volunteered to assist those arrested by staging law students in courtrooms to coordinate where legal assistance was needed. And faculty and students organized an information center to give information in-person or by phone to family members inquiring about relatives who were somewhere in the court system. They also organized refresher courses in criminal court procedures for volunteer attorneys who practiced non-criminal specialties.

D.C. Riots, 1968 ("University Responds to Needs of Strife-Torn City," Georgetown Record, April 1968

On April 5, President Johnson ordered 4,000 regular Army and National Guard troops into Washington, D.C. With the University’s permission, a few hundred of these used McDonough Gym as a dormitory. Main Campus remained at a safe distance from the disturbances; the closest incident was at 33rd and O Streets, NW. However, the smoke-filled sky over the city was very visible from campus, as were the flames from burning buildings.

Student Strike, 1970 (Illustration from the Georgetown Voice, May 1970)

The Student Senate voted for a strike of classes from Wednesday, May 6, to Friday, May 8, 1970; similar strikes took place on campuses across the country. The strike came two days after the deaths at Kent State University and centered around demands for the U.S. Government to cease escalation of the Vietnam War into Cambodia and Laos and to unilaterally withdraw all troops from southeast Asia. The resignation of Fr. Robert K. Judge, S.J. as Dean of Men was also sought.

Student Strike, 1970 (News from Georgetown University: “Georgetown Suspends Classes,” May 7, 1970)

After faculty support of the student strike, the University suspended classes on May 7th for the rest of the semester. Students were able to meet with faculty and take final exams on a voluntary basis. Alternatively, they were able to settle for existing grades or make arrangements to submit papers in place of final exams.

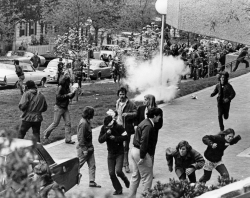

May Day protests, 1971 (May Day protesters on campus, pictured in Ye Domesday Booke, 1971)

During the weekend of May 1-2, 1971, Washington, D.C. was inundated with protestors against the Vietnam War. Most of the protestors camped in West Potomac Park, adjacent to the National Mall. On Sunday, May 2, at 6:30 a.m., D.C. police cancelled the demonstrators’ camping permit and drove them out of the park. Many were told that the University had opened to protestors and, throughout the day, a steady stream of protestors arrived on campus, setting up tents on the athletic fields and – once it began to rain – filling every dorm.

The protestors were peaceful and the University concluded, in consultation with the Metropolitan police, that it would be close to impossible to clear the buildings and opted not to try. The protestors departed between 5:30 and 6 a.m. the next morning (May 3).

May Day protests, 1971 (Photographs of the main gates and the east side of Lauinger Library, May 3, 1971)

After 8 a.m. on May 3, 1971, waves of demonstrators who had been attempting to block traffic were driven through the streets of Georgetown by police using tear gas. As the gas reached campus, a decision was made at 9:15 a.m. to cancel exams – 15 minutes before they were due to start. However, it appears that not all faculty were notified of the decision in time and some exams still took place. An area for washing off pepper and tear gas was set up in the Bles Building and student marshals worked, at great personal risk, to try to keep police and demonstrators apart. Afternoon exams were cancelled at 12:20 p.m.

By 4:15 p.m., the demonstrators, who were estimated by the University to have numbered about 2,500, had left campus. Student estimates placed the number higher. There were no reports of serious personal injury and, surprisingly, property damage was quite limited. American University and George Washington University experienced similar situations to Georgetown and the three universities were in continuous contact, sharing information and advice.

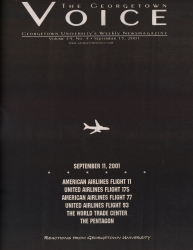

September 11, 2001 (View from the Murray Room on the fifth floor of Lauinger Library on the morning of September 11, 2001. Photograph by David Hagen)

On September 11, Main Campus, which had been locked down by campus police stationed at the entrances, closed at noon. With many understandably reluctant to use public transportation, students who lived off campus, faculty and staff joined the throngs of walkers who crowded the city’s streets and who streamed across the bridges into Virginia.

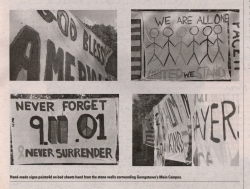

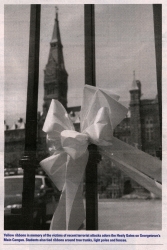

September 11, 2001 (Images from Blue & Gray, volume 11, number 2, September 24-October 8, 2001)

Classes were held on September 12, although academic learning was not the immediate priority on campus over the next few days. One of the key features of the University’s immediate response was to create ways for people on campus to come together, support each other, and try to process the tragedy. In addition to vigils and prayer services, students had the opportunity to meet with faculty members in a series of symposia on the topics of foreign affairs, philosophy and theology.

Friday, September 14, was proclaimed as a National Day of Prayer by President Bush. Georgetown remained open but classes ended at noon and the Healy Hall bell tower tolled from 12 to 12:05 p.m., signaling moments of silence and reflection. Prayer services and other observances took place across campus that afternoon. Students gathered on Copley lawn to create and hang banners in tribute to the victims. These joined the yellow ribbons on the main gates and at the entrances to campus buildings, and the American flags hanging from dorm windows.

Curated by Lynn Conway, University Archivist