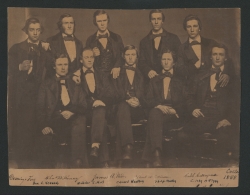

Georgetown College Class of 1858

This is the first known photograph of a Georgetown College graduating class. Among those pictured: Beverly C. Kennedy, Louisiana; Nicholas S. Hill, Maryland; Edward Wooten, Maryland; Philip A. Madan, Cuba; Cornelius John O'Flynn, Michigan; Domingo Toro, Chile; Charles B. Kenny, Pennsylvania; James A. Wise, Washington, D.C.; Samuel A. Robinson, Georgetown; and Caleb C. Magruder, Maryland. Of the ten students shown, at least three, Kennedy, Hill, and Wooten, served in the Civil War.

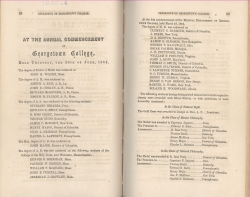

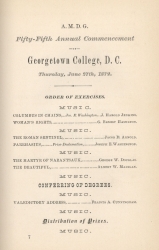

Commencement program, 1859

Signs of threatening national strife appear to be reflected in the decidedly militaristic attitude of some of the student speeches delivered at the commencement ceremony, with titles such as: The French Revolution of ’92; The Battle of Fort Moultrie; and The Battle of Hastings.

Description of Philodemic Society debate on the question of Should the South Secede, December 18, 1859, as recounted by J. Fairfax McLaughlin on pages 97- 98 of his book, College Days at Georgetown and Other Papers, 1899

As with the commencement speeches, debates of the Philodemic Society were colored by national events. The debate on December 18, 1859, was so heated that, according to McLaughlin: a scene followed not unlike some of those then frequently occurring in Congress – a free fight. As a result, Georgetown President John Early, S.J., suspended Society meetings for the rest of the academic year to prevent any recurrence.

Proceedings of the Philodemic Society, October 13, 1860

All miscellaneous business being now finished the Society proceeded to debate the question “whether the Union will be dissolved in the case of the election of Lincoln as President of the U.S.” . . . After being warmly debated [the question] was decided in the negative.

Georgetown College Cadet, ca. 1860

Tintype photograph of an unknown pre-Civil War Georgetown College Cadet with button. Gift of the Liljenquist Family, 2010.

House Diary. Entry for January 4, 1861

On Friday, January 4, 1861, classes were cancelled as the College participated in the national day of fasting and humiliation proclaimed by outgoing U.S. President James Buchanan in an attempt to avert the imminent evils from the Republic.

Rector’s Consultations. Entry in Latin for February 18, 1861

The Faculty of the Medical Department, fearing that Lincoln’s inaugural on March 4, 1861, might spark a riot, requested permission to copy the record of decrees awarded to their students since their founding in 1851, so it would not be lost if their building, then at F and 12th Streets in northwest Washington, was damaged.

First and last page of petition from ten members of the senior class, asking for permission to leave campus and return home, April 10, 1861 (Rev. John Early, S.J. Papers, box 1, folder 1)

. . . Our presence here any longer would be attended but with little good to us, for we are giving utterance to a plain and undisguised truth when we say that there is not one amongst us who is now able to devote that time, interest, energy and requisite spirit to the pursuits of the Class, which our parents, our friends, our teachers and yourself, Reverend Sir, have just and reasonable claims in expecting of us; while all we have dear on earth, our country (the South), our parents and our brethren call loudly upon our presence at our respective homes . . .

The petition also asked for all classes to be suspended, a request not granted, although the senior class was allowed to graduate without further studies. Of the ten singers of the petition, at least five fought in the War – four in the Confederate Army, and one, Francis P.B. Sands of Washington, D.C., in the U.S. Navy.

Letter from parent and Nashville resident William P. Bryan to Georgetown President John Early, S.J., April 21, 1861

As this letter (written eight days after the surrender of Fort Sumter) shows, the unease of students on campus was matched from a distance by many of their parents who were concerned about the potentially dangerous location of the College: . . . As war seems inevitable and Washington may be the first place of attack, I am quite uneasy on account of my son Macon. I could not rely more confidently than I do upon your efforts to take care of every boy in the College, but if the forces of the Southern Confederacy should march upon the Capitol, they may cross the Potomac at or about Georgetown, and are as likely to be met by the United States Troops in your vicinity as any where else. In this event, so bloodless a collision as that at Fort Sumter is hardly to be hoped for, and a stray bomb from either party would not discriminate between an unoffending College boy and a member of the opposing corps . . .

Letter from Nashville agent of the Adams Southern Express delivery service to his Washington, D.C., counterpart, requesting an advance so that Macon Bryan could buy tickets and travel home to Tennessee, April 25, 1861

Macon Bryan had enrolled at Georgetown on September 28, 1860. He left shortly after his father’s letter was written to return home to Tennessee. In fact, during the month of April 1861 more than 100 southern students left, out of a total student body of 286.

James Ryder Randall, enrolled at Georgetown from 1848-1856 (James Ryder Randall Collection, box 1, folder 13)

A journalist and poet, Randall is probably best known as author of the words to Maryland, My Maryland, which became known as The Marseillaise of the Confederate cause. In 1861, while chair of English Literature at Poydras College, Pointe-Coupée, Louisiana, Randall read a newspaper report of the Baltimore Riot. This clash between pro-South civilians and Union troops in Randall’s native city on 19 April, 1861, resulted in what is commonly accepted as the first bloodshed of the Civil War. The account Randall read stated, incorrectly it turned out, that Francis X. Ward who had been a classmate and friend of Randall’s at Georgetown was among twelve civilians killed in the clash. The report moved Randall to write the words to what is now the Maryland state song.

[Maryland,] My Maryland! by James Ryder Randall. Autograph copy presented by the author to Georgetown, October 1, 1907 (James Ryder Randall Collection, box 1, folder 4)

The despot's heel is on thy shore,

Maryland!

His torch is at thy temple door,

Maryland!

Avenge the patriotic gore

That flecked the streets of Baltimore,

And be the battle queen of yore,

Maryland! My Maryland!

“A Reminiscence of the War” by an “Old Student,” Georgetown College Journal, December 1878

In this account, George Gibson Huntt (C1849), a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Cavalry, relates how, in May 1861, while tasked with selecting camping sites around the district, he visited his alma mater in order to use the upper floors of its buildings to locate suitable sites on the Virginia side of the river and how, as he and his companions were leaving campus, one student stepped out of the crowd who had gathered to watch and shouted: “Three Cheers for Jeff Davis and the Southern Confederacy!” Such a yell arose in response as is seldom heard within the old College walls. We were much amused by the enthusiasm of the young men and Capt. Prime, turning in his saddle, smiled and exclaimed, “Hurra! Boys, Hurra! I was once a boy myself.”

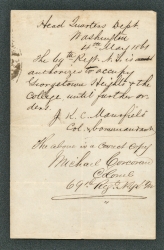

Copy of Notice of Occupation by the Sixty-Ninth New York Regiment, May 4, 1861 (Rev. John Early, S.J. Papers, box 1, folder 1)

The 69th Regt. N.Y. is authorized to occupy Georgetown Heights and the College, until further orders.

The Sixty-Ninth Regiment of the New York State Militia, known as the “Irish Regiment,” numbered fourteen hundred. The around sixty students still on campus had to quickly move themselves and their possessions to Old North from the buildings on the south side of the Quadrangle which were turned over for use of the Regiment.

Memorandum from the Colonel of the Sixty-Ninth Regiment of the New York State Militia, written from Headquarters, Sixty Ninth Regiment of N.Y.S.M., Georgetown College, D.C., [May] 1861 (Rev. John Early, S.J. Papers, box 1, folder 1)

This lists the campus buildings occupied by virtue of an order from Brig. General Mansfield, U.S.A.

“Letter from a Member of the Sixty-Ninth, Washington, May 5th, 1861.” Clipping from an unidentified newspaper, originally pasted in the front of University account book, Ledger G

. . . Yesterday . . . we were sent to where we are now – the Roman Catholic College of Georgetown, a regular palace . . . We do not know how soon we are to be ordered to Virginia, which state I am now looking at from my window, with only about 300 yards of water between us . . .

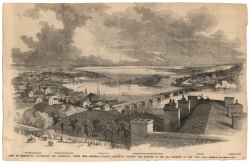

"View of Georgetown, Washington and Alexandria taken from Columbia College, Georgetown Heights, the Quarters of the 69th Regiment of New York." Reproduction of illustration from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, May 25, 1861 (Scan courtesy of the Ge

The writer of the caption incorrectly identifies Georgetown as “Columbia College,” perhaps confusing us with Columbian College, the original name for George Washington University.

As this view illustrates, the campus was an attractive candidate for occupation with its commanding views of Georgetown, Washington, D.C., and the Virginia shore. The two watchers in the lower, right corner are on the roof of Gervase Hall.

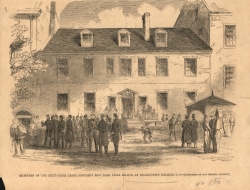

“Quarters of the Sixty-Ninth (Irish) Regiment, New York State Militia, At Georgetown College, D.C.” Harper’s Weekly, June 1, 1861

The illustration shows the Sixty-Ninth in the Quadrangle, in front of Old South. The Regiment was billeted at Georgetown for three weeks, during which time President Lincoln and several members of his cabinet visited to review them.

Transcript of letter from B.E. McMahon to Mr. Sumner, Georgetown College, May 10, 1861. Woodstock Letters, November 1964

Bernard McMahon, a Jesuit Scholastic and teacher in Georgetown’s preparatory division, describes the impact of the Sixty-Ninth, as well as the only recorded visit by Abraham Lincoln to campus: . . . They are quite domesticated now and give extremely little trouble, save a general soiling of the establishment. They enjoy themselves hugely with the small boys’ gymnasium and alley. A sentinel guards the large boys’ gymnasium from everybody except the students. The see-saw for a time was the principal object of attraction. They’d get some green one, coax him on to it, and while in the air give it a twitch and dump him off . . . We have a regimental drill at three and company drill all day long. “Uncle Abe,” accompanied by Mr. Seward, Cameron and others, drove up to the College on Wednesday and reviewed the troops . . .

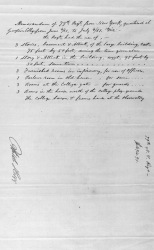

Memorandum and Estimate of Property injured at Georgetown College, D.C., by the 79th Regiment from New York, from June 4, 1861 to July 4, 1861 (Copy from original in War Department Records in the National Archives)

The Seventy-Ninth, known as the “Highland Regiment” because of the many Scots it contained, arrived on campus on June 4, 1861. The House Diarist comments that the Jesuits found them to be the worst sort of scoundrels, constantly fighting amongst themselves, in contrast to the better behaved Sixty-Ninth. There was much relief when, after a month, the Seventy-Ninth followed the Sixty-Ninth to the west.

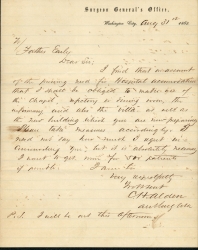

Letter to Georgetown President John Early, S.J., from the Surgeon General’s office, requisitioning campus buildings, August 31, 1862 (Rev. John Early, S.J. Papers, box 1, folder 1)

Buildings on the south side of campus, as well as the College’s villa in Tenleytown, were requisitioned because of a pressing need for Hospital accommodation for 500 patients. The “new building” mentioned appears to be Maguire Hall, construction on which began in 1854. Apparently, Old North was spared because of the intercession of a Union General, General Amiel Weeks Whipple, whose sons William and David were enrolled. Because of this, Georgetown was able to continue in operation, although enrollment dropped as low as seventeen. The campus was not returned to the College’s control until February 1863.

Letter from General A.W. Whipple to Georgetown President John Early, S.J., Headquarters 3rd Division III Corps, Falmouth, Virginia, March 31, 1863 (Rev. John Early, S.J. Papers, box 1, folder 2)

Special Collections holds a number of letters between General Whipple and President Early, including this one (written five weeks before the General’s death) on the subject of obtaining Catholic prayer books for his troops: I find that there are many Catholics in this Div. who are anxious to obtain Catholic prayerbooks. I think the small pocket manual is what they need. Col. Bowman who commands one of my Brigades – a Protestant – and myself will gladly pay for enough to amount to $25. This I think will buy about 100. May I ask you to take the trouble of ordering them to be boxed . . .

General Whipple was killed at Chancellorsville. His funeral was held at Trinity Church in Georgetown on May 10, 1863. President Early preached and U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and his cabinet were present. Fort Whipple in Arlington, Virginia, later renamed Fort Myer, was named for him.

Georgetown College as seen from the Observatory, ca. 1864

In this photograph, the earliest known of campus, the requisitioned buildings – Maguire, Old South, Mulledy, and the Infirmary (Gervase) – are seen on the right side.

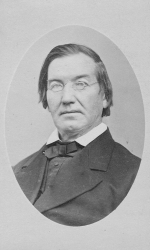

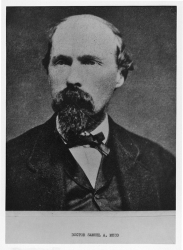

John Early, S.J. Georgetown President, 1858-1866 and 1870-1873

President Early proved to be a firm and prudent leader during the often difficult years he guided the institution. One of the reasons Georgetown survived the Civil War was that he was able to ensure that faculty and administrators maintained a neutral attitude to the conflict, at least publicly. Many of the Jesuits associated with Georgetown favored the South – some even had relatives fighting on the Confederate side – but these sentiments were successfully tempered by an understanding that any open demonstration of support could provoke attacks on Catholic institutions in general and on Georgetown in particular.

Letter from U.S. Senator Milton S. Latham to Georgetown President John Early, S.J., Washington City, D.C., September 16, 1861 (Rev John Early, S.J. Papers, box 1, folder 2)

Senator Lantham writes about James [R. Kittrell], a student from Eutaw, Greene County, Alabama, who was stranded at the College: I have tried every way to get the youngster off, but cannot do it. I send you enclosed a letter of Messrs. Wells Fargo and Co. to whom I had applied to have their agent take charge of him at Cincinnati; you will see that it is impossible to pass him. I shall write to his brother the facts in the case, in the mean time please keep him at his studies. I do not know how his accounts stand with you, but I hope you understand I am in no way responsible for his bills . . . Please inform James of the impossibility of getting him to his mother.

James was still at the College a year later, in September 1862, although his name does not appear in student lists after this date. It appears he was eventually able to make his way home, as he enlisted in Greene County as a private in Company B, Seventh Regiment, Alabama Cavalry, on June 20, 1863.

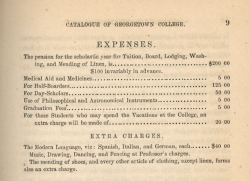

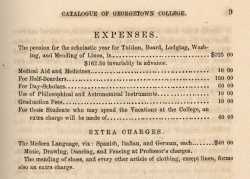

Expenses from Catalog of the Officers and Students of Georgetown College, District of Columbia, for the Academic Year 1862-1863 (left) and from Catalog of the Officers and Students of Georgetown College, District of Columbia, for the Academic Year 1863-18

With drops in enrollment and students stranded on campus, their bills not necessarily being paid, the College’s revenue decreased sharply. In 1863, a combination of reduced income and inflation forced a fee increase. This marked the first rise in the cost of tuition and board in forty years, from $200 per year to $325.

Louis Otto Hein. Memories of Long Ago, 1925 (SPCOLL General - 93A26)

Students who remained on campus had many opportunities to observe the course and impact of the fighting. Hein, nephew of the painter James Alexander Simpson, enrolled in Georgetown in 1861. In his autobiography, he recounts events of June 29, 1861: . . . I was an interested spectator of a huge procession of vehicles crossing the aqueduct-bridge over the Potomac, loaded with sight-seeing passengers comprising tourists, members of Congress and civil government officials, on their way to watch the progress of the anticipated Union victory at Bull Run, from a position of safety on a hillside which overlooked the battlefield. On the afternoon of the same day, I saw the panic stricken visitors returning in flight, followed by the fleeing soldiers of McDowell’s army, many of whom were without caps, coats and weapons which had been thrown away by them in their precipitate retreat . . .

First page of letter from student E.S. Reily to family members, Georgetown College, April 6, 1862

Sometimes, rather than simply observing from the campus grounds, students were more proactive. Edward Reily, a student from Adams County, Pennsylvania, here describes a somewhat spontaneous visit to Virginia: . . . Yesterday the papers informed us that hereafter no “pass” would be required from civilians to cross the Potomac. Whereupon a number of the students of the venerable and world-renowned Georgetown College, headed by a Prefect, set out upon and [sic] expedition to the seat of war to see what they could see . . . we at length arrived upon the “sacred soil” of Virginia (which “sacred soil” by the way we found to differ very little from common mud, and which stuck to my shoes as if I was a successionist). After trudging on a while we came to Fort Corcoran . . . passing on we saw many strange sights and scenes: strings of baggage wagons as long as the good old city of McSherrystown [Pennsylvania], winding their slow course over the heights of Arlington; now a troop of cavalry, again a squad of infantry; here and there an encampment on some hill-side . . .

Reily graduated as Valedictorian of his class in 1864, was admitted to the D.C. Bar, and became a professor in Georgetown’s Law School.

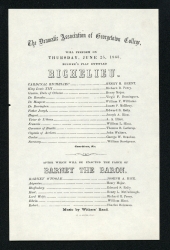

Handbill for Richelieu, performed by the Dramatic Association of Georgetown College, June 25, 1863

Student activities, including plays, continued during the Civil War, albeit in a scaled-back manner. Edward S. Reily, writer of the previous letter, is named in the cast list.

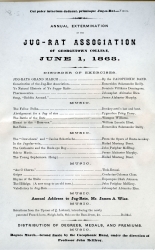

Program from the Annual Extermination of the Jug Rat Association of Georgetown College, June 1, 1863

Until the 20th century, students who violated minor rules on campus were punished by having to memorize and publicly recite lines of Latin poetry. When a culprit had lines to learn, he went to the “jug” or detention room and was considered by his fellow students to be a “jug rat.” Punishment lines were cumulative and it was possible for a student who was given to rule-breaking and not blessed with an aptitude for memorization to be in the “jug” for most, if not all, of a school year, although lines did not carry over from year to year. A Jug Rat Association operated sporadically during the second half of the 19th century. Its main activity appears to have been an annual “extermination,” held in June after the end of classes. A program of music and speeches, the “exterminations” were a parody of commencement ceremonies and generally attracted large external audiences.

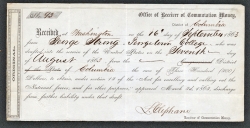

Receipt for George I. Strong, S.J., for payment of commutation money, September 16, 1863

By 1863, there was a shortage of military manpower in the Union. As a result, Congress passed the first conscription act in U.S. history on March 3, 1863. Federal agents set quotas of troops to be furnished, with all male citizens between twenty and thirty-five years of age and all unmarried men between thirty-five and forty-five liable to be called for a three-year term of military service. Those drafted could avoid enlistment by hiring a substitute or paying the government $300 in commutation money. George I. Strong, S.J., was Professor of Mathematics at Georgetown in 1863. By payment of $300, he was able to obtain exemption from military service.

Certificate of Exemption for Drafted Person on Account of Disability, Washington, September 24, 1863

Georgetown faculty also successfully sought exemption from the draft on medical grounds. Assistant Professor Frederick Holland, S.J.’s exemption was granted by reason of Deficient Amplitude and Expansion of Chest.

Account of “Commencement Day” at Georgetown College. Sunday Morning Chronicle, July 6, 1862

Commencement exercises were held throughout the Civil War; John Gilmary Shea in his centennial history of the University comments that this evinced the determination of the Faculty to maintain the old order, even amid the most discouraging circumstances.

Toward the end of the Chronicle article, reference is made to the little sons of the late distinguished Senator Douglas. This was Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas, who ran as the Northern Democratic Party nominee in the 1860 Presidential election. Douglas died on June 3, 1861.

Note pasted inside the front cover of University account book, Ledger M, regarding silver medals for the 1862 commencement

Gold and silver medals were awarded annually at commencement to students with the highest academic achievements. Given its financial constraints, the College was able to fabricate silver medals in 1862 only by melting down the silver spoons of students who had left. At least three of the students named, Edward O’Brien, Emile J. O’Brien and Alfred F. Peschier (all from Louisiana), were serving in the Confederate army by the time of the commencement.

Program from the Annual Commencement of Georgetown College, June 30, 1864

Most of the graduates were from Union states, however, students from Confederate states and abroad are also listed.

As the program indicates, Georgetown was awarding degrees to students from the College of Holy Cross, Worcester, Massachusetts. When Holy Cross opened in 1843, it was unable to secure a charter from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts because of its exclusively Catholic enrollment and, without a charter, it could not award degrees. A charter was finally granted in 1865 but, in the interim, Georgetown conferred degrees on Holy Cross graduates.

Georgetown College Class of 1864

Pictured, left to right: R. Ross Perry, District of Columbia; Charles T. Closs, Nebraska; Thomas Rudd, Kentucky; Cypriano Zegarra, Peru; Edward S. Reily, Pennsylvania; and James P. McElroy, New York.

Pass issued by the Army of Northern Virginia, September 9, 1862, granting Bernard Maguire, S.J., (Georgetown President from 1853 to 1858 and 1866 to 1870) permission to pass outside the lines of this Army upon his pledge not to reveal anything concerning

Minutes of the Medical Department, February 2, 1863

. . . Dr. [Thomas] Antisell proposed the establishing of a new chair in accordance with the suggestion of the Surgeon General U.S.A. to be styled Chair of Military Surgery, Physiology and Hygiene. Approved. The Medical School, then the Medical Department of Georgetown College, prospered during the War. Its enrollment significantly increased and by 1863, as the only medical school in Washington, it was a major training center for surgeons of the Union armies. The Chair of Military Surgery, Physiology and Hygiene was the first of its kind in the nation.

“Reminiscences of the Old Medical School” by Daniel S. Lamb, M.D. 1867. The Hoya, November 13, 1925

In this article, Dr. Lamb remembers the Medical Department as it was at the end of the Civil War: In the year 1864, during the Civil War, while I was on duty in the military hospitals in Alexandria, Va., I began the study of medicine, and in October 1865, came to Washington for duty in the Army Medical Museum and to attend the course in Medicine at Georgetown Medical School. The school was the housed on F street northwest, the building east of the corner of Twelfth street, now 116 F Street . . . the medical building was about thirty feet front and three stories high; the auditorium and faculty room on the second floor, the dissecting room on the third; on the first floor was a meat shop. So far as I know and believe, there was no immediate connection between the dissecting room and meat shop; just a coincidence . . .

Union troops on the Virginia side of the Potomac, some time after the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863

The Georgetown campus can be seen, top left, on the hilltop.

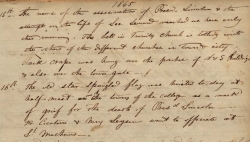

House Diary entries for April 15 and 16, 1865

The news of the assassination of President Lincoln and the attempt on the life of Sec Seward reached us here early this morning. The bell in Trinity Church is tolling with the others of the different churches in the town and city. Black crape was hung over the porches of N[orth] and S[outh] Buildings and also over the town gate. The old star spangled flag was hoisted to half mast on one of the towers of the college as a mark of grief for the death of President Lincoln.

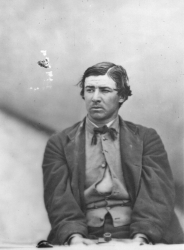

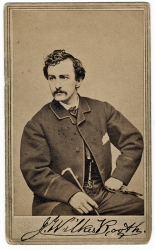

David Herold, enrolled from 1855 to 1858

Of the eight people convicted in the conspiracy to assassinate President Lincoln, three were Georgetown alumni – David Herold, Samuel Arnold, and Dr. Samuel Mudd. Herold was one of four conspirators hanged.

On April 14, 1865, Herold guided Lewis Payne to Secretary of State William Seward's house, where Herold waited outside with Payne’s horse while Payne attempted to stab Seward to death. The same night, Herold helped the injured John Wilkes Booth to escape after Booth shot Lincoln, going with Booth to the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd so that in Booth’s injured leg could be treated. Booth and Herold were caught together at Garrett's farm in northern Virginia in the early morning of April 26.

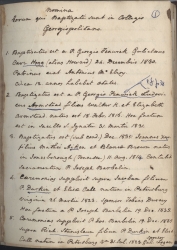

Entry for David Herold in the Georgetown College Entrance Book, 1850-1895

Information (such as age, religion, father’s name, and initial class placement) about enrolling students was recorded in entrance books. Details on David Herold, who enrolled in 1855 aged thirteen, can be seen six entries from the bottom of the page. Interestingly, the word, alas, has been added in a different, presumably later, hand.

It was not unusual for a thirteen year old to be attending Georgetown at this time. The average age of entering students was fourteen, with the full course of studies lasting seven years – three in the preparatory division, followed by four in the collegiate division.

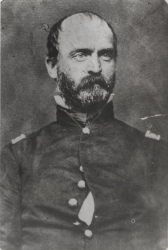

Samuel Bland Arnold (left), enrolled from 1844 to 1845, and Dr. Samuel Alexander Mudd (right), enrolled from 1851 to 1852

Arnold was born in Georgetown, although his family later moved to Baltimore. He enrolled in the College when he was ten years old and later attended St. Timothy's Military Academy in Catonsville, Maryland, where he was a classmate of John Wilkes Booth. After Lincoln’s assassination, Arnold was arrested on suspicion of complicity. He admitted to involvement in plans with Herold and Booth to kidnap Lincoln and exchange him for Confederate prisoners but denied any part in the assassination. Sentenced to life imprisonment, he was pardoned by U.S. President Andrew Johnson in 1869.

Dr. Mudd was born in Charles County, Maryland. After attending Georgetown, he enrolled at the University of Maryland Medical School in Baltimore, graduating in 1856. Hours after President Lincoln’s shooting, John Wilkes Booth and David Herold arrived at Mudd’s Maryland home, seeking treatment for the bone Booth had broken in his left leg. Mudd was subsequently linked to the assassination conspiracy and arrested. Although he denied any involvement, arguing that he did not recognize Booth whom he had previously met, he was sentenced to life imprisonment, avoiding the death penalty by a single vote of the military commission conducting the trial. President Johnson pardoned him, like Arnold, in 1869 and he returned to Maryland, where he lived until his death in 1883.

John B. Guida, S.J. (Photograph from the Woodstock College Archives)

Born in Italy, Fr. Guida taught Philosophy at Georgetown from 1863 to 1868. He had the misfortune to bear a resemblance to John Wilkes Booth and, as a result, to be arrested in the aftermath of President Lincoln’s assassination. According to one account of the incident, he was arrested near Georgetown and taken to a military camp in Virginia where he was held, unable to prove his identity, until the real John Wilkes Booth was located.

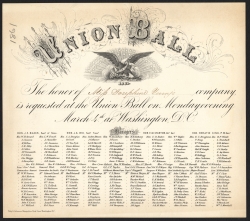

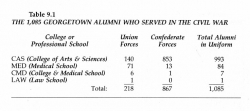

The 1,085 Georgetown Alumni Who Served in the Civil War. Table from R. Emmett Curran’s A History of Georgetown University, Georgetown University Press, 2010

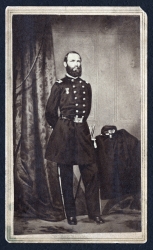

Charles F. Rand, M1873. Captain, U.S.A. Pictured in Blue and Gray: Georgetown University and the Civil War, Georgetown University Alumni Association, 1961

On April 15, 1861, following the Battle of Fort Sumter, eighteen year old Charles Rand was at the Eagle Hotel in Batavia, New York, when a telegram arrived announcing that President Lincoln had called for volunteers to enlist. Rand enlisted on the spot, apparently becoming the first volunteer for the Union. He was assigned to Company K, Twelfth New York Volunteer Infantry. After limited training, the regiment traveled south, with their first engagement occurring on July 18, 1861, at Blackburn’s Ford, Virginia. After two masked batteries of Confederate artillery opened fire, the inexperienced regiment scattered, with the exception of Rand. Alone, he faced the charging Confederates until their Colonel ordered his troops to cease fire, commenting that Rand was too brave to die.

Congressional Medal of Honor Citation for Charles F. Rand. (From the Congressional Medal of Honor Society web site)

In 1897, Rand received the Congressional Medal of Honor (created in 1863) for his actions at Blackburn’s Ford. His was not the first Medal of Honor awarded but his acts were the first for which the Medal was given. Captain Rand left the Army in 1870, attended the Georgetown Medical School, and graduated in 1873. He died on October 13, 1908, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Julius P. Garesche, enrolled from 1833 to 1837. Assistant Adjutant General, U.S.A. (Julius P. Garesche Papers, box 1, folder 8)

Garesche attended West Point after leaving Georgetown and later served in the Mexican War. He was appointed chief of staff to General William Starke Rosecrans, commander of the 14th Army Corps, also designated the Army of the Cumberland, in November 1861. He served in this role until his death on December 31, 1862, at the Battle of Stones River, Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Initially buried on the battlefield, Julius was later reburied at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Letter from Julius P. Garesche to Georgetown President John Early, S.J., July 22, 1861 (Rev. John Early, S.J. Papers, box 1 folder 1)

Written the day after the Confederate victory at the first Battle of Bull Run, the first major land battle of the Civil War, Garesche implores President Early to send priests to minister to captured Union soldiers in Confederate hands: All our sick and wounded, I suppose, are in the hands of the Confederate army. At least one third of them must be Catholics - with no priests to care for them! Now this is a heaven-sent opportunity to show the men of both sides, to the whole country that our good Priests, true ministers of peace, though they have not girded themselves with weapons and made themselves ridiculous in uniforms, are prompt to offer their services . . .

The College was receptive to Garesche’s plea and three Jesuits left campus for Manassas, Virginia, on the same day his letter was written.

Joseph B. O’Hagan, S.J., Georgetown faculty member from 1855-1857. Chaplain to the Army of the Potomac

A former Georgetown faculty member, Father O’Hagan was assigned by the provincial superior to be a military chaplain. He wrote a series of letters which vividly describe his experiences, one of which, written on December 18, 1862, after the Battle of Fredericksburg, includes the following passage: The fight of last Saturday was the most sanguinary I have yet seen during the war. Our division was held in reserve on the north side of the river till Saturday, about 1 o’clock P.M. We were stationed on a high hill which commanded a fine view of the entire battle. The Confederates had one of the most magnificent positions, both natural and artificial. Their front was composed of a crescent of hills, along the sides of which extended their breastworks, for miles back. I am confident that half a million men could not have taken them. I saw one of them assaulted four times, and our men, column after column, cut down as fast as they could advance at a double quick! Next day I examined the field with a powerful glass, and I never could imagine so many dead could be left on one field. They were actually in heaps . . .

Commission appointing Joseph B. O’Hagan as Chaplain, 73rd Regiment, New York Volunteers, 1861 (Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus, box 10, folder 10)

After his discharge from the military, O’Hagan returned to Georgetown. In 1872, he became President of Holy Cross College.

Nathan Goff, Jr., enrolled from 1860 to 1861. Major, U.S.A.

In 1861, aged nineteen, Goff left his studies at Georgetown, returned to his home in Clarkesburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), and subsequently volunteered as a private in the Third Virginia Volunteer Infantry. In 1863, he was mustered in as Major in the Fourth West Virginia Cavalry. Captured by Union forces in 1864, he was for a period held in Libby Prison, Richmond, Virginia, hostage for the exchange of a Confederate officer, Major Thomas D. Armsey, who had been captured while recruiting for the Confederate Army behind enemy lines. In 1881, he briefly served as Secretary of the Navy under the Hayes Administration. From 1913-1919, he served in the U.S. Senate.

Confederate Seal. Unknown Date

The seal prominently features George Washington on horseback, surrounded by a wreath of the main agricultural products of the Confederate States: wheat, corn, tobacco, rice, and sugar cane. The date of February 22, 1862, commemorates the date of the inauguration of Jefferson Davis as President of the Confederacy. February 22 is also George Washington’s birthday.

Lewis A. Armistead, C1830-1831. Brigadier-General, C.S.A.

Armistead resigned his U.S. Army commission in May 1861 and was appointed Colonel of the 57th Virginia Regiment in the Confederate Army. In April 1862, he was appointed Brigadier-General and assigned to command a brigade in what later became Pickett's Division of the Army of Northern Virginia. On the third day of the Battle of Gettysburg, July 3, 1863, he led his brigade in an assault on the center of the Union line as part of Pickett’s Charge. The brigade penetrated the Union lines more deeply than any other Confederate unit, an event now known as the High Water Mark of the Confederacy, but was quickly overwhelmed by a Union counterattack. Armistead was shot three times in the counterattack and died at a Union field hospital two days later.

Baptismal record for Lewis Armistead, March 31, 1831. Entry 2 in Ledger of Baptisms and Confirmations at Georgetown College, 1830-1920

Armistead was baptized on campus by Fr. George Fenwick, S.J., who was on the College faculty.

Henry Heth, enrolled from 1837 to 1838. Major General, C.S.A.

From Richmond, Virginia, Heth attended West Point after leaving Georgetown. He resigned from the U.S. Army in 1861 and was appointed Colonel of the Forty-Fifth Regiment, Virginia Infantry. In February 1863, he was transferred to the Army of Northern Virginia and was later promoted to Major General. At Gettysburg, it was his Division that made first contact with Union troops. He is said to have been the only officer in the Army of Northern Virginia who addressed General Robert E. Lee by his first name.

Matthew Fontaine Maury, G1845. Commander, Confederate States Navy

Known as the "father of oceanography,” Maury was born near Fredericksburg, Virginia. In 1842, he was appointed Superintendent of the Depot of Charts and Instruments of the Navy Department and began publishing research on oceanography and meteorology. In 1855, he published The Physical Geography of the Sea, recognized as the first textbook of modern oceanography. Maury resigned his commission in the U.S. Navy in 1861 and joined the Confederate Navy. He perfected an electric torpedo which significantly disrupted northern shipping. The Secretary of the Navy said of it in 1865 that it cost the Union more vessels than all other causes combined.

After the War, Maury joined the faculty of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) and advocated the creation of an agricultural college to complement it. This led to the establishment of the Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College (Virginia Tech) in Blacksburg, Virginia. Maury died in 1873 and is buried between U.S. Presidents James Monroe and John Tyler in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

Bronze plaque in memory of Matthew Fontaine Maury, placed on pier of telescope in Georgetown University Observatory, June 4, 1962

Some Reminiscences in My Life by J. Carroll Payne, undated

. . . When I was fourteen years old, after the war was over, my father sent me to Georgetown University. He had promised my mother to bring her children up as Catholics, as she was one herself, he being an Episcopalian, so he wrote to the College and asked if they would take me and subsequently my second brother Gaston and finally Ralph, and educate us on the terms he could not pay for us at that time but would do so in the future if he was able to do so, endeavoring to carry out his promise to my mother. I went to Georgetown in December 1869, as the college took us all year to year on those terms. My father subsequently as his business began to return paid the entire debt he owed the college . . .

J. Carroll Payne from Warrenton, Virginia, was a nephew of Confederate Senator Thomas Jenkins Semmes. He graduated from the College in 1876 and, according to his Reminiscences, served on the student committee that selected blue and gray as Georgetown’s colors. As Payne’s writings show, the Civil War left many in the South in a financially perilous position. As a result, the amount of financial aid to Southern students increased. According to R. Emmett Curran’s A History of Georgetown, nearly a seventh of students from below the Potomac were given either free tuition and board or reduced fees.

View of Georgetown and the Aqueduct Bridge, November 11, 1865. Photograph by William Morris Smith

Letter from Senator Stephen R. Mallory, C1869, recollecting a lack of evident “sectional bitterness” among the Georgetown student body after the Civil War. Georgetown College Journal, December 1906

. . . I entered the College in November 1865, when the echoes of the strife that had shaken the foundations of our institutions were still resounding through the land. Strange to say, however, within the College walls there were no evidences of sectional bitterness and the war and merits of the Union and Confederate causes were never subjects of general discussion by the students. This was not due to the absence of partisan feelings among them, but rather to the promptings of good sense that realized the inutility and folly of such controversies . . .

Mallory served in both the Confederate Army and Navy. His father, Stephen Mallory, was Confederate Secretary of the Navy.

Program from Commencement, June 27, 1872

The neutral attitude to the conflict maintained by the College during the War continued during the early post-War years. The 1872 commencement program lists G[eorge] Ernest Hamilton among the student speakers. At the ceremony, he spoke on the subject of women’s rights. That was not, however, the topic he wished to cover. His original talk was on Confederate General Robert E. Lee. This became an issue, however, as U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant (to whom Lee had surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse) was to attend commencement. Patrick F. Healy, S.J., Vice President of Georgetown and Prefect of Studies, told Hamilton that the speech could not be delivered. Hamilton argued that Grant was a great admirer of Lee and the speech would be favorably received but Fr. Healy won the argument and the topic was changed.

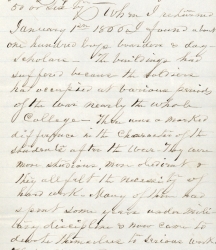

Notes of Bernard Maguire, S.J., Georgetown President from 1853-1858 and 1866-1870, with comments on the demeanor of post-War students [pg. 15]. (Bernard A. Maguire, S.J. Papers, box 1, folder 1)

. . . When I returned January 1st 1866, I found about one hundred boys, boarders and day scholars. The buildings had suffered because the soldiers had occupied at various periods of the war nearly the whole College. There was a marked difference in the character of the students after the war. They were more studious, more obedient & they all felt the necessity of hard work. Many of them spent some years under military discipline & now came to devote themselves to serious work . . .

Sodality of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Georgetown College, 1865-1866

Postbellum students seem to have exhibited a more religious sensibility than their antebellum equivalents and large numbers of them joined the Sodality, which replaced the debating societies as the most popular organization on campus. Students from the South were particularly prominent in its membership.

Georgetown College, ca. 1867

The College, prompted by rising rates of vagrancy and theft caused by the failing post-War economy, sought permission to built a stonewall on its eastern boundary. The wall along Warren Street (now 37th Street) was completed in 1867. Healy Hall would be begun ten years after this picture was taken.

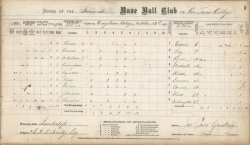

Scores for a baseball game between the Quicksteps and the Stonewalls, October 26, 1869

R. Emmett Curran notes in his A History of Georgetown that: Although the sport [baseball] was played in both Northern and Southern cities well before 1861, the Civil War may have inadvertently made baseball truly the national past-time since it was much played in Northern and Southern military camps alike throughout the conflict.

After the Civil War, baseball clubs were formed across the country. Many colleges established teams, Georgetown among them, and, by 1869, the College boasted two baseball clubs, the Stonewalls and the Quicksteps.

Informal baseball game on Copley Lawn, ca. 1886

It has been suggested that origins of the word, Hoya, which formed part of the College yell or cheer, Hoya! Hoya! Saxa!, can be linked to the Stonewalls baseball club. The theory is this: a student using a mixture of Greek and Latin (which were emphasized by the curriculum) dubbed the Stonewalls, Hoia Saxa. Hoia is the Greek neuter plural for what or what a, while saxa is the Latin neuter plural for large or rough rocks. Taken together, Hoya Saxa literally means what rocks – the suggestion being that the players were as hard as rocks. Others have speculated that Hoya Saxa referred not to the team but to its surroundings. As this early baseball photograph shows, home plate was near the stonewall along 37th Street.

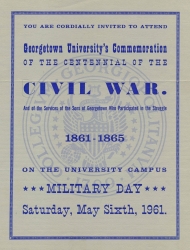

Program for Georgetown University’s Commemoration of the Centennial of the Civil War, May 6, 1961

The ceremonies were held in Gaston Hall because of rain. Georgetown President Edward B. Bunn, S.J., noted: We are here today to honor in particular the Georgetown men who took part in the War of a century ago – those who fell in battle, or died from their wounds and privations in the service of the North, or of the South; as well as those, who, having done their duty as soldiers, returned to take up their lives again, not as Federals or Confederates but as Americans.

Georgetown Sings Songs of the Civil War, 1961. 33 ½ RPM record

Side 1

The Star Spangled Banner

Maryland, My Maryland

Aura Lee

Alma Mater

Side 2

Blue and Gray Medley

The Glee Club performed Civil War-era songs at the Centennial Commemoration and these were later recorded under the direction of Music Professor and Glee Club director Paul Hume. The record sold for $1.50, a price that included shipping.

Letter from Kenneth H. Powers, Regimental Historian of the Sixty-Ninth Regiment of New York, to Georgetown President Edward B. Bunn, S.J., May 11, 1961

The Sixty-Ninth Regiment, as represented by First Lieutenant Kenneth H. Powers, returned to campus for the Centennial commemoration.

Replica of Georgetown University Boat Club banner (One of seven produced as part of the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the reconstitution of the crew team in 2008)

The Boat Club was formed in March 1876. One of its first actions was to appoint a Committee on Colors. Georgetown did not have colors and it was felt that they were needed so that supporters on shore could identify the crew team during races. An article in Georgetown College Journal of June 1876 (the only account of the Committee’s work that has survived), explains how the Committee, looking for colors to express the feeling of unity that exists between the Northern and Southern boys of the College, recommended the adoption of blue and gray. A subsequent Journal describes how young ladies from the neighboring Visitation Academy immediately sewed a half blue, half gray banner, with the inscription Ocior Euro (“Swifter than the Wind” in Latin), and presented it to the College.

Curated by Lynn Conway, University Archivist