Introduction

VISUAL ARTS OF THE AMERICAS had its origins in the preparations for the 2003 John Carroll Awards, given each year by the Georgetown University Alumni Association to recognize outstanding dedication to Georgetown, remarkable public service, and notable life achievement. Since the awards ceremonies were to take place in San Juan, Puerto Rico, the Georgetown University Library produced a short video, Library Lens on Latin America, to describe the Library’s resources in Latin American studies, including works from the Georgetown University Art Collection.

The number of items in the Art Collection by Latin American artists was relatively small, but included some by prominent printmakers of the twentieth century. Additionally, several artists from the United States—the area in which the Fine Print Collection is strongest—had depicted Latin American and Caribbean subjects in their work. After researching and organizing these pieces during the video's production, the Art Collection decided to exhibit several of them, and other related items, to provide an opportunity for viewers to see quality works from the Collection not often shown and studied. Art Collection staff previously had undertaken independent research on the visual culture of Canada; by adding objects from and about Canada to the exhibit, the theme Visual Arts of the Americas was developed.

“The Americas”

In considering the concept, Visual Arts of the Americas, viewers may reasonably wonder what is the definition of “of.” What, other than the happenstance of geography, and the historical accidents that led to the name “America,” provides any unity to these visual works so that they may be considered “of the Americas”? Is it work produced within the Americas with subjects recognizably of the Americas? Or by artists of the Americas regardless of choice of subject? Or work produced by artists originating from or located outside the Americas that depicts subjects recognizably of the Americas? All of these designations are represented in Visual Arts of the Americas.

What, too, are the significance of national political boundaries or cultures defined by nationhood? Since the nineteenth century, many historians of the western hemisphere had attempted to explore the past by considering the interrelationships and interdependence of the peoples of the many nations of the Americas. The first professor of history at the University of California, Bernard Moses (1846-1930), wrote in 1898: “American history, in its proper sense, embraces all attempts to found and develop civilized society on this continent, whether those attempts were made by the English, the French, the Portuguese, or the Spanish....[W]e should adopt a more comprehensive view of American history, and consider our institutions and achievements in relation to the institutions and achievements of other nations that began as we began on the virgin soil of a new world.... ”1

The trend received a significant boost from one of Moses’ successors at the University of California. At a 1932 address in Toronto to the American Historical Society, its president, the eminent historian Herbert Eugene Bolton (1870-1953), decried the “provinciality” of historical research, that had focused on the United States (or other national histories) as the primary theatre of incidence and consequence.2 Bolton said: “Thirteen of the English colonies led the way; Spanish and Portuguese America followed. Throwing off their status as wards, English, Spanish, and Portuguese colonists set themselves up as American nations. Viewed thus broadly the American Revolution takes on larger significance....Ever since independence there has been fundamental Western Hemisphere solidarity....We need a [historian] to sketch the high lights and the significant developments of the Western Hemisphere as a whole....”3 Particularly influential was Bolton’s theory of “borderland zones,” which “are vital not only in the determination of international relations, but also in the development of culture....”4 During his three decades at the university, Bolton taught and trained many graduate and undergraduate students in his theories.

Such notions about the nature of civilization in the Americas continued to find adherents. In a 1981 book that is now regarded by many as prescient and insightful, Washington Post reporter Joel Garreau presented his economic and political thesis of The Nine Nations of North America: “Forget about the borders dividing the United States, Canada, and Mexico, those pale barriers so thoroughly porous to money, immigrants, and ideas....Consider, instead, the way North America really works. It is Nine Nations. Each has its capital and its distinctive web of power and influence. ” 5

Visual Arts of the Americas reflects the fluidity of ideas across political broders throughout the Americas, the interest in and influence upon people of one region by those of another. The stories and ideas depicted begin within the tumult of early European nationhood as its explorers and colonists encountered the culturally rich civilizations of the "New World"; and continue to the present era, with artists reacting to the rapid and often unsettling changes from past to future.

Latin America and the Caribbean

Beginning in 1533 and throughout the 18th century, Spain occupied much of the New World, introducing Old World culture and tradition to the indigenous civilization. Among the most influential of these institutions was religion. As was frequently the case in the exploration incursions at the time, religious missionaries soon followed the initial conquering forces into the New World. In 1571, with the arrival of Jesuit priests from Spain, also brought religious teachings, artifacts, and artwork.

The history of Cuzco, an Incan town in south-central Peru, is an example of the influence of religion on the indigenous people. In addition to (and perhaps to supplement) sermons and other religious teachings, Spanish master painters taught local artists to paint in the European style. This group of artists, known as “Cuzco School,” mixed religious imagery with more traditional Incan and Andean imagery and characteristic painting style and methods to create a truly inventive works. This mixing of cultural aesthetics in the arts echoes some of what also transpired in politics, religion, economy, etc, with the meeting of the "Old" and the "New" World. The Cuzco school is still in very active today.

Among the work of the Cuzco School included in this exhibit are a canvas Lamentation from the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries, that could be rolled into a scroll for easier transport by traveling priests; from the same century, a Virgin of Sorrows; from a century later, an interesting painting of Pope Gregory I (Gregory the Great); and in reproduction, one of the Georgetown University Art Collection's important paintings, a large Our Lady of Montserrat, the famous Spanish scene depicted within Andean-type mountains and with South American people.

Even after these countries became independent of European government, Latin American arts still followed the example of Europe. In a period of upheaval, uncertainty, and change brought by independence, Latin American artists embraced the authority and convention represented by the European traditions of fine arts and continued to follow the art model offered by their former stewards. In fact, several art schools and academies were opened in the nineteenth century that taught formal arts curricula, in the tradition of Old Europe.6

However, several political events in the twentieth century spurred a change in the Latin American arts culture. The Mexican Revolution of 1910 sparked the beginnings of an indigenous modernist movement in Latin America, marking a refreshing departure from the influence of "Old Europe." Moreover, the disparaging events of the first World War fueled a deeper disillusionment with Europe both politically and emotionally. The circumstances of the war and political and military disgrace of the "Old Europe" motivated a desire, in most of Latin America, to move away from the "Old World." Endemic pro-socialist sentiments developed in the region, their exponents sometimes attempting to suggest a romanticized link between the "proletariat"/peasant culture and pre-Spanish Incan, Andean and Aztec societies, such as with the notion of shared lands and wealth in these ancient Latin American civilizations.7

From this cauldron of politics, nationalism, and modern aesthetics arose a "renaissance" of innovative arts, styles and methods was noticeable in the arts of most of the region by the mid-1920s. One of the first schools to emerge at this time was the “Mexican School.” Well-known for its work with murals, the group was initially comprised of nationalistic artists, with little formal training. These artists produced what was generally regarded as public and monumental art or “the people’s art,” aimed at addressing socio-political, secular and cultural issues. The Mexican School was also an attraction to many other Latin American artists, who often traveled to Mexico City and drew inspiration from the aesthetic of the school. This art movement is represented by a number of artists in this exhibit, such as Carlos Merida, and younger artists Francisco Mora, Francisco Zuñiga, and from the United States, Pablo O'Higgins, and Elizabeth Catlett Mora, one of the giants in the history of artists from Washington, who was attracted to the Mexican School for its political and aesthetic ideals.

Other "schools of thought" soon followed. As with their European counterparts, much of the origin of the modern Latin American art movements can be found in literature and literary precedent, during a time of rapid urban growth. The concept of modernismo refers not only to literature, but also defines an aesthetic subscribed to by many Latin American artists from 1900s to the 1930s.8

A significant pioneer of the Mexican School, Carlos Merida relayed a “modern aesthetic based on native art and native subjects” in his works.9 Born in Guatemala in 1891, Merida lived in New York City, Mexico City, and Paris. His art was influenced by abstraction in the ancient art of Mexico, Guatemala, and the modern works of artists such as Miró, Klee, and Kandinsky. The subject matter of Merida’s work was taken from the beliefs, customs, and folklore of his culture; unlike many of his contemporaries and followers, Merida was not an overtly political artist. He focused on the secular formal and technical aspects of art. Three of his color lithographs are included in Visual Arts of the Americas.

The success of the Mexican School received notice throughout the Americas, as well as in Europe. The works produced by the artists were saturated by nationalism and the concept of "return to the source," a return to tradition while also exploring the "avant-garde." With the success and attention given to the Mexican School, many Latin American artists immigrated to the United States to work and exhibit. Their presence in the U.S. affected and inspired many North American artists. Similarly to the way in which Spain had influenced indigenous arts almost 400 hundred years before, Latin America now exercised a similar influence over Western arts.

Ultimately, the period of Mexican and Latin American modernism marked a breakthrough for those non-Western artists previously receiving lesser notice by the "art world" of Europe and the United States, establishing the importance of those artists on the political, social, and global periphery in the modern art world. Visual Arts of the Americas showcases some candid works from these talented and expressive artists.

Canada

While campaigning in the federal elections of 1904, Canada’s seventh prime minister, Wilfrid Laurier (1841–1919; served 1896–1911), told a Toronto audience that “the twentieth century shall be the century of Canada and of Canadian development. For the next seventy-five years, nay for the next hundred years, Canada shall be the star towards which all men who love progress and freedom shall come.” 10

Whether the Honorable Mr. Laurier's prediction fell true is a topic for discussion beyond the scope of this essay. Nonetheless, Canada and its civilization serve as an intriguing case study of the legacies of Renaissance exploration and of the development of political, legal, cultural, and social traditions of that era as they blossomed into those of a great, trans-continental young nation. As with another such case study, its neighbor the United States, Canada is an immigrant nation of worldwide attraction; such development has felt the imprint of an often disputatious but necessarily inseparable relationship between the English colonial era and the great cultural traditions of France and French Canada that were, in fact, the origin of European civilization in upper North America; and Canadian culture has felt the inescapable influence of the neighboring nation that eventually would supplant its English colonial "home country" as the most powerful nation on earth. Visual Arts of the Americas offers of sampling of works from, of, and about Canada, reflecting the fascinating flux of ideas and aspirations that have developed in the five hundred years of Canadian civilization.

Much like their Mexican counterparts, Canadians expatriate artists looked (in their case not north but south) to the U.S. for direction in modern art in the beginning of the twentieth century. New York City became a meeting point; the new center for art production, especially after the World Wars left a disillusioned image of "Old Europe." As a former colony, Canada moved to distance itself from the cultural patronage of Europe and in doing so became involved in the socio-political artistic movements that were happening in New York City at the time. From the often divisive regionalism in Canada, ironically, many Canadian artists found a unifying factor in modern art movements in New York City, a very "un-Canadian" place. Much like the artists of the Mexican School, New York City artists addressed social change and political issues in their work. However, where Mexican arts explored public forms of expression, the American (and therefore Canadian) approach was much more intellectual and abstracted. Among those artists who sought acceptance in New York were Caroline and Frank Armington in the early twentieth century, and Jean-Paul Riopelle during the Abstract Expressionist movement a few decades later.

Visual Arts of the Americas includes rare book illustrations from France during its colonial period in Canada; work reflecting important developments in printmaking during the nineteenth century; and modern masters of graphic arts in Canada.

For further reflection...

Visual Arts of the Americas offers an opportunity for viewers to consider the importance of cultural, historical, and aesthetic ideas that have been a part "of the Americas."

- David C. Alan, Art Technician

Olubukola A. Gbedagesin, Intern

1 Bernard Moses, “The neglected half of American history,” University Chronicle, I (Berkeley, 1898); reprinted in Lewis Hanke, ed., Do the Americas have a common history? A critique of the Bolton theory (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1964), pp. 55, 58.

2 reprinted as “The Epic of Greater America,” American Historical Review, XXXVIII (1933), pp. 448–474; included in Hanke, p. 67–100.

3 idem, pp. 78, 98, 100.

4 idem, p. 99.

5 Joel Garreau, The nine nations of North America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), p. 4.

6 Oriana Baddeley and Valerie Fraser, Drawing the line: art and cultural identity in contemporary Latin America (Verso Publishers, London: 1989).

7 www.backpackersinc.com/NEWS%20AND%20ARTICLES/n+a2002/abril/socialismin%20latin%20america.htm

8 Jacqueline Barnitz, Twentieth-century art of Latin America (University of Texas Press, Austin: 2001).

9 Jacinto Quirarte, “Mexican and Mexican-American Artists in the United States 1920-70,” in The Latin American spirit: art and artists in the United States 1920-1970 (New York : Bronx Museum of the Arts in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1988).

10 Desmond Morton, A short history of Canada (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd.), p. 158.

Special acknowledgment is given to Curatorial Intern Olubukola Gbadegesin, for invaluable assistance in the preparation of artwork for exhibit, and research on the artists and historical themes.

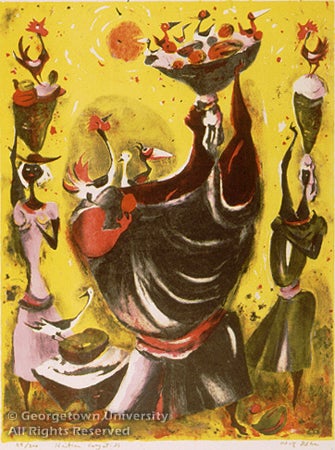

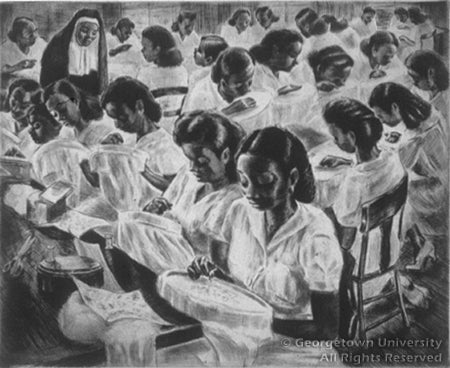

Haitian Women

Irving Amen, b. 1918; New York, New York

1965

color intaglio

16 1/4 x 11 3/4 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

Cosmographiae introductio cum quibusdam geometriae ac astronomiae principiis ad eam rem necessariis

1554

5 5/8 x 3 3/4 "

Venetiis: Impressum per Francisci Bindonis, 1554; verso leaf 28

Solola - Guatemala

Alfred Bendiner, b. 1899; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania , d. 1964; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

1960

ink and watercolor

13 3/4 x 16 3/4 "

Georgetown University Art Collection

Four Photographs from the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, Saint Louis

Ernest Wilson Boyer, b. 1885; Tamaqua, Pennsylvania, d. 1949; New York, New York

1904

prints range from approx. 2 1/2 x 3 1/2 " to 3 3/4 x 4 3/4 "

Georgetown University Manuscript Collection

Helen King Boyer Collection

Tower of Jewels

Ernest Wilson Boyer, b. 1885; Tamaqua, Pennsylvania, d. 1949; New York, New York

1914

pencil on paper

16 x 11 3/8 "

Georgetown University Art Collection

Helen King Boyer Collection

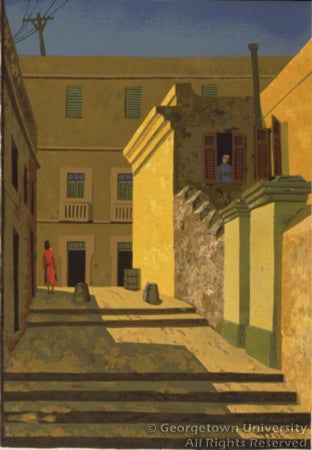

Escalerilla

Luis Germán Cajiga, b. 1934; Quebradillas, Puerto Rico

1965

color lithograph

17 3/8 x 12 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

Pedro Menendez de Aviles

José Camarón y Boronat, b. 1730; Segorbe, Spain, d. 1803; Valencia, Spain

Published by Fran(cis)co de Paula Marti, 1791

engraving; ed. unknown

11 3/4 x 7 1/4 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

Al Aire Libre

Pilar Castañeda, b. 1941; Ciudad de México, D.F.

1969

color etching; ed. 4/25

11 1/2 x 8 3/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

Cajón de Bronce las Condes

Reproduction: Ramón Catalán, (dates unknown) (Chile)

1930s

oil on canvas

39 x 50"

Georgetown University Art Collection

Mexican Kitchen

Louis Henry Jean Charlot, b. 1898; Paris, France, d. 1979; Honolulu, Hawai'i

1947

lithograph; ed. 250

13 1/8 x 9 7/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

James Patric Joseph Murphy Collection

Commemorative Certificate

engraving and photolithograph

6 5/8 x 11 "

at lower right: LIT Y TIP DEL COMERCIO · CARACAS; 1931

Georgetown University Manuscript Collection

W. Coleman Nevils, S.J.

Reproduction: N. (Madam Ferdinand) Vervenka, (dates unknown) (Czechoslovakia)

1932

oil on canvas

35 1/2 x 29 1/2

Georgetown University Art Collection

Presidential Gallery

The Lamentation

Cuzco Era

seventeenth - eighteenth century; Peru

oil on canvas

15 3/4 x 25"

Georgetown University Art Collection

Our Lady of Montserrat

Reproduction: Cuzco Era

eighteenth century; Peru

oil on canvas

67 x 42 1/2 "

Georgetown University Art Collection

Pope Gregory I (Gregory the Great)

Cuzco Era

eighteenth or early nineteenth century; Peru

oil on linen, attached to board

39 x 27 1/2 "

Georgetown University Art Collection

The Virgin of Sorrows

Cuzco Era

seventeenth century; Peru

oil on canvas

16 x 10 3/4 "

Georgetown University Art Collection

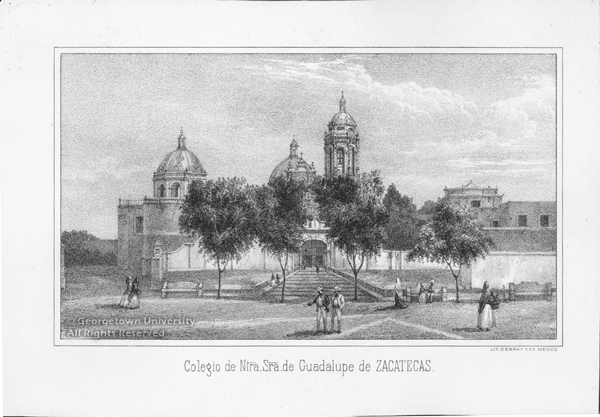

Collegio de N(os)tra. S(eño)ra. de Guadalupe de Zacatecas

DeBray and Co., nineteenth century; Mexico

1858

lithograph; ed. unknown

4 x 7"

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

The Library of John Gilmary Shea

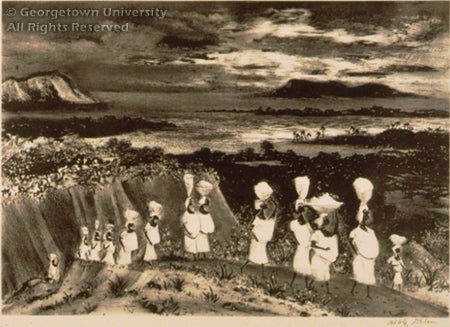

Caribbean Processional

Adolph Arthur Dehn, b. 1895; Waterville, Minnesota, d. 1968; New York, New York

1954

lithograph; ed. 250

13 7/8 x 9 3/4 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

James Patric Joseph Murphy Collection

Haitian Caryatids

Adolph Arthur Dehn, b. 1895; Waterville, Minnesota, d. 1968; New York, New York

1952

lithograph; ed. 84/200

16 x 12 1/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

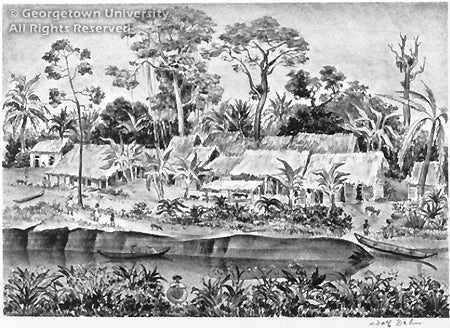

Venezuelan Village

Adolph Arthur Dehn, b. 1895; Waterville, Minnesota, d. 1968; New York, New York

1946

lithograph; ed. unknown

9 1/8 x 13 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

James Patric Joseph Murphy Collection

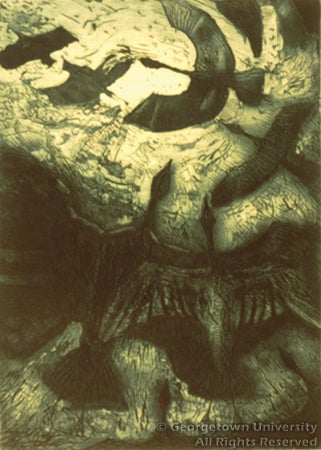

Mexico

Moshe Gat, b. 1935; Haifa, Israel

1959

etching and aquatint; ed. E./A.

13 3/4 x 9 3/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

Street Carnival

Andrea Gómez, b. 1926; Ciudad de México, D.F.

n.d.

wood engraving; ed. 3/56

10 3/4 x 14 1/4 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

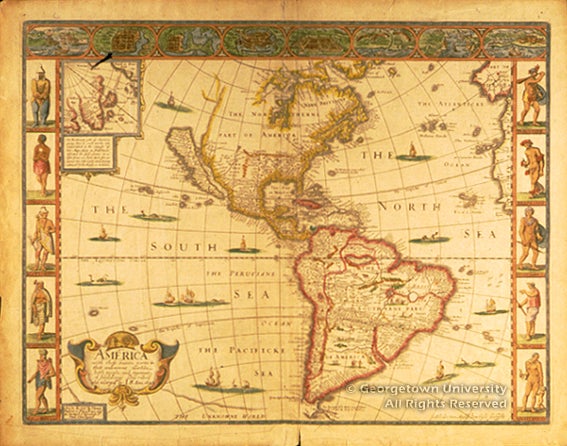

The Description of America

Abraham Goos, active early to middle seventeenth century; Amsterdam, the Netherlands, John Speed, b. 1552; Farrington, Cheshire, England, d. 1629; London, England

1676

engraving; color added

15 3/8 x 20 1/4 "

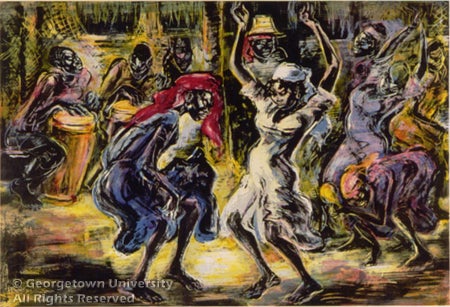

Haitian Dancers

Marion Greenwood, b. 1909; Brooklyn, New York, d. 1970; Woodstock, New York

c. 1953

color lithograph; ed. unknown

12 x 18 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

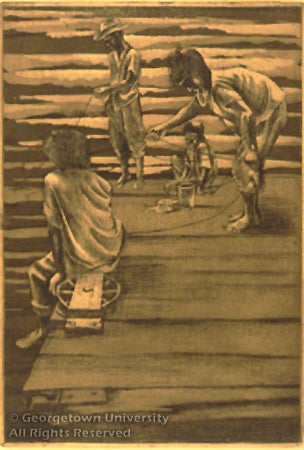

Lace Makers, Puerto Rico

Irwin Hoffman, b. 1901; Boston, Massachusetts, d. 1989; New York, New York

1944

etching; edition unknown

9 3/4 x 11 7/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

Puerto Rican Folk Song

Irwin Hoffman, b. 1901; Boston, Massachusetts, d. 1989; New York, New York

n.d.

etching; ed. unknown

10 3/4 x 13 7/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

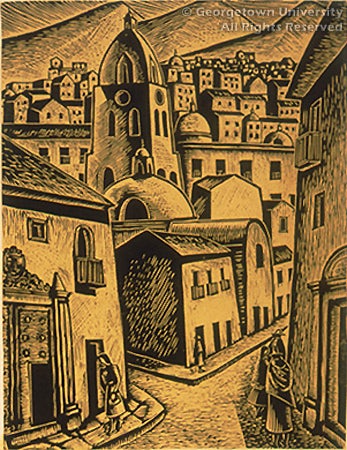

"Calle Sagarnaga" - La Paz

Genaro Ibanez, b. La Paz, Bolivia; twentieth century

c. 1930s

woodcut; ed. unknown

10 7/8 x 8 1/4 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

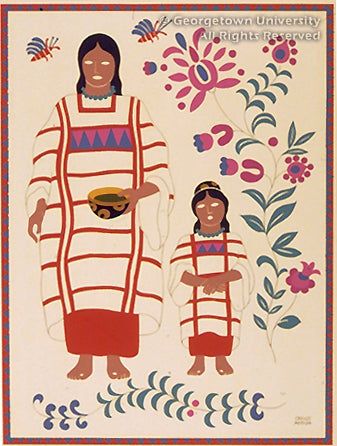

15 Friques- Estado de Oxaca

Carlos Merida, b. 1891; Xelahu, Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, d. 1984; Ciudad de México, D.F.

n.d.

color lithograph; ed. unknown

12 1/4 x 9 1/4 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

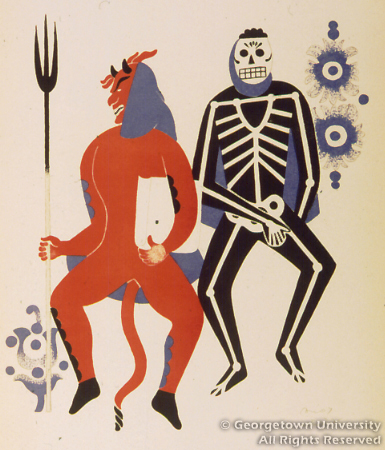

The Devil and Death

Carlos Merida, b. 1891; Xelahu, Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, d. 1984; Ciudad de México, D.F.

1940

color lithograph; ed. 437/500

17 1/2 x 12 1/2 "

from Carnavales de Mexico: Diez Litografias Originales, en color (Mexico, 1940)

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

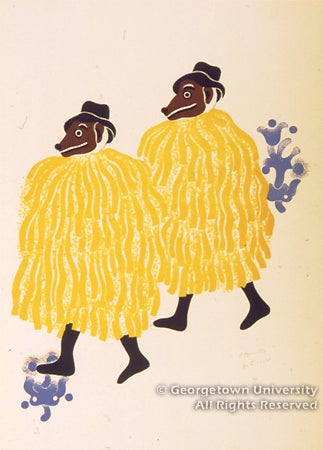

"Dog People"

Carlos Merida, b. 1891; Xelahu, Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, d. 1984; Ciudad de México, D.F.

1940

colorlithograph; ed. 437/500

17 1/2 x 12 1/2 "

from Carnavales de Mexico: Diez Litografias Originales, en color (Mexico, 1940)

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

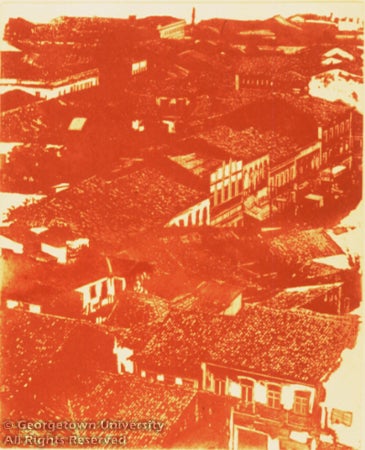

Casario de San Luis - Maranhaõ

Thereza Miranda, b. 1928; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1979

photo etching; ed. artist's proof 5/10

14 1/8 x 11 1/2 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

Sacada - Catete - Rio de Janeiro

Thereza Miranda, b. 1928; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1981

photo etching; ed. artist's proof 6/10

23 1/4 x 11 5/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

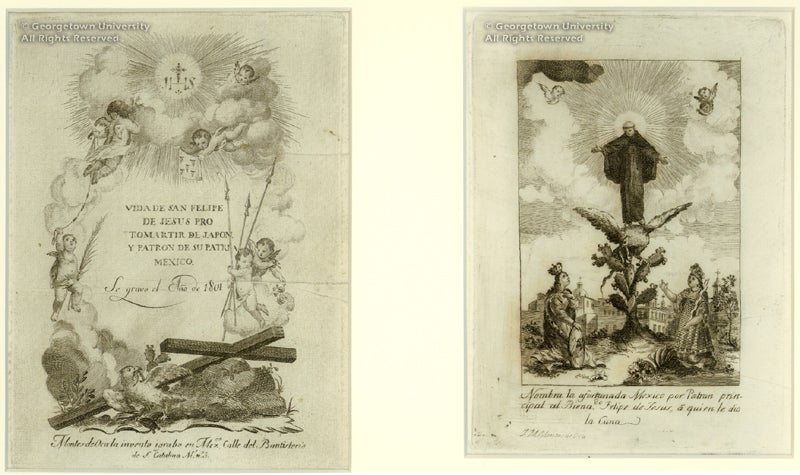

Vida de San Felipe de Jesus, Protomartir de Japon y Patron de su Patria Mexico

1801

engraving

Title Page (left): 6 7/8 x 5" ; Felipe Named as Patron Saint (right): 6 5/8 x 4 3/4 "

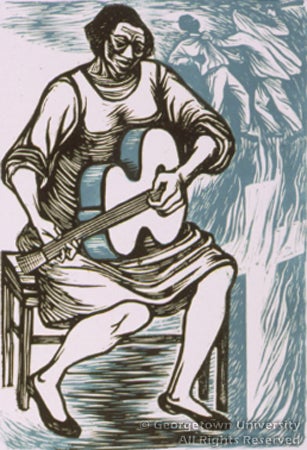

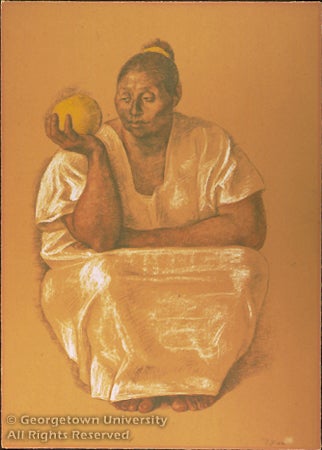

Blues

Elizabeth Catlett Mora, b. 1915; Washington, D.C.

1947

color linocut; ed. 5/35

7 3/8 x 5"

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

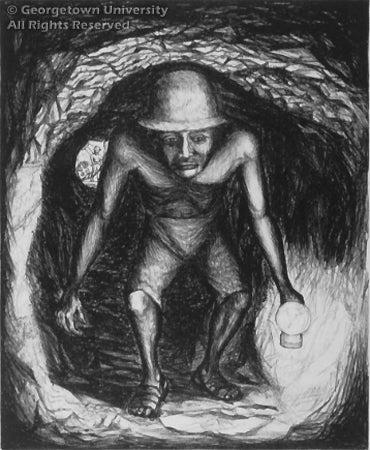

Silver Mine Worker

Francisco Mora

1940s

lithograph

15 x 17 3/4 "

from Mexican People: 12 Original Signed Lithographs by Artists of the Taller de Grafica Popular, Mexico City (New York: Associated American Artists, 1940s)

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

The Market

Pablo O'Higgins (Paul Esteban Higgins), b. 1904; Salt Lake City, Utah, d. 1983; Ciudad de México, D.F.

1940s

color lithograph

15 x 17 3/4 "

from Mexican People: 12 Original Signed Lithographs by Artists of the Taller de Grafica Popular, Mexico City (New York: Associated American Artists, 1940s)

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

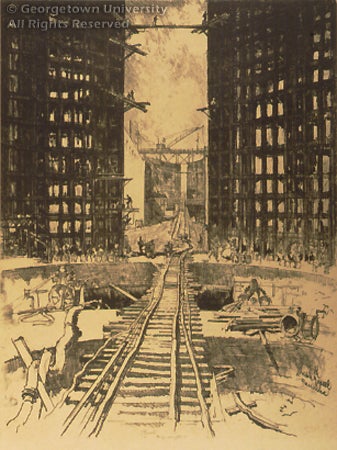

Between the Gates of Pedro Miguel

Joseph Pennell, b. 1860; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, d. 1926; Brooklyn Heights, New York

1912

lithograph; ed. 50

22 1/8 x 16 7/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

The Guard Gate, Gatun Lock

Reproduction: Joseph Pennell, b. 1860; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, d. 1926; Brooklyn Heights, New York

1912

etching/drypoint; ed. 60

12 3/8 x 9 3/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

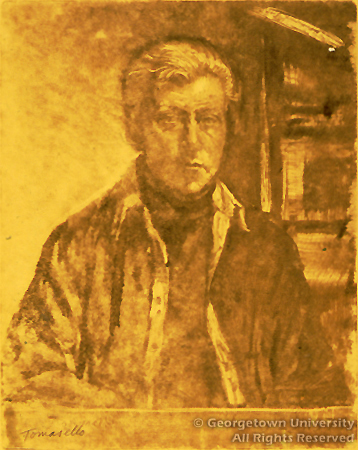

Self-portrait

Luis Tomasello, b. 1915; La Plata, Argentina

1977

monoprint

9 7/8 x 7 7/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

The James W. Elder Collection of Artists' Self-Portraits

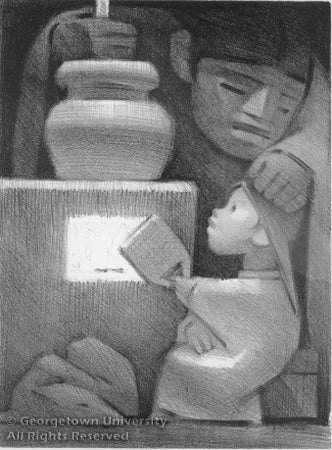

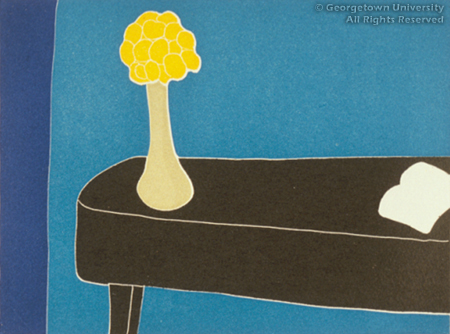

The Piano

Fernando Torm, b. 1944; Santiago, Chile

1979

color etching; ed. 5/150

4 1/2 x 6 "

from Blue Interiors

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

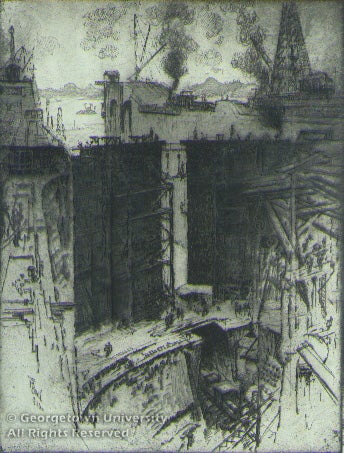

Panama Pacific Exposition Construction

Reproduction: Cadwallader Washburn, b. 1866; Minneapolis, Minnesota , d. 1965; Brunswick, Maine

c. 1915

lithograph; ed. unknown

14 x 9 5/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

Map of the world

Martin Waldseemüller

13 5/8 x 24 7/8 "

Insuper quatuor Americi Vespucii Navigationes

original, Saint-Dié: 1507; in facsimile, New York: The United States Catholic Historical Society, 1907

The Burro Station (Taxco, Mexico)

Reynold Henry Weidenaar, b. 1915; Grand Rapids, Michigan, d. 1985

etching, drypoint; ed. unknown

16 3/4 x 12 3/4 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

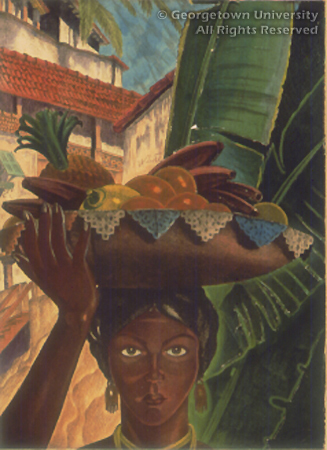

The Fruit Vendor, Mexico

Alfredo Ximenez, (dates unknown) (United States)

n.d.

etching with hand coloring; ed. unknown

10 7/8 x 7 7/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

El Pastor

Mariana Yampolsky, b. 1925; Chicago, Illinois, d. 2002; Ciudad de México, D.F.

linocut; ed. unknown

5 7/8 x 7 1/8 "

Georgetown University Fine Print Collection

University Librarian Artemis G. Kirk; Associate University Librarian for Special Collections Marty Barringer; Curator of Prints Emeritus The Reverend Joseph A. Haller, S.J.; Assistant Curator LuLen Walker; Joseph N. Tylenda, S.J., Director of the Woodstock Theological Library at Georgetown; Assistant Manuscripts Librarian Scott S. Taylor; Archivist Lynn Conway; Isabelle Ringuet, Reference Archivist, National Archives of Canada; Manuscripts Librarian Nicholas B. Scheetz C'74; Director of Development Marji Bayers; Development Assistant Stephanie S. Hughes; Special Events Manager Caroline W. Griswold; Graphic Artist David Hagen, Multimedia Specialist Nicholas J. Brazzi, and Multimedia Specialist Jovanna M. Frazier.

Roderick Quiroz G'91 graciously provided translations from the Spanish language.

Matting by Frames By Rebecca, Inc.; Silver Spring, Maryland.