September 18, 2020

In 1912, at the outset of his career, American diplomat Cornelius Van Engert booked a ticket on the famous British ocean liner Lusitania. Engert sailed on the vessel from New York City to England. Three years later, the ship became the source of international controversy when a German submarine torpedoed it. The ship sank and 1,198 people of the 1,959 aboard drowned. The Cornelius Van Engert Papers, which are preserved in the Booth Family Center for Special Collections, contain a document granting Engert a trip on the Lusitania in 1912.

In 1904, the Cunard Line in Britain started construction on the Lusitania. The company hoped to make sizeable profits by providing reliable service on the sea voyage across the Atlantic Ocean between England and the United States. Cunard completed construction in 1907. The Lusitania was the largest ship in the world, measuring 787 feet in length and 31,550 tons in weight. It was also to become known for its speed: in October 1907, the ship crossed the Atlantic in record time.

Born of Dutch parents, Cornelius Van Engert received a B.A. from the University of California Berkeley in 1908 and an M.A. in 1909. He also attended Harvard University for one year as a non-degree student. On March 12, 1912, Engert joined the U.S. Foreign Service as a student interpreter to the Ottoman Empire (Turkey) in Constantinople.

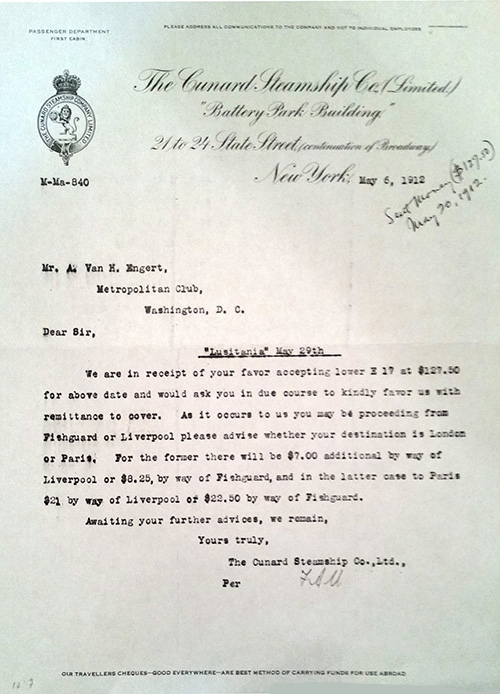

Box 12 folder 3 of the Cornelius Van Engert Papers contains a document concerning Engert’s voyage on the Lusitania. Dated May 6, 1912, the document was sent to Engert by an official from the Cunard Steamship Company. The Cunard Company sent the item from New York City on company stationery. The representative addressed Engert as “Mr. A. Van H. Engert” at the Metropolitan Club in Washington, D.C. When Engert first entered the U.S. Foreign Service, he used the name “Adolph Van H. Engert.” He eventually started using Cornelius, one of his middle names, as his first name.

In the letter, the correspondent acknowledged that lower E 17 on the ship had been reserved for a trip on May 29 for Engert for the price of $127.50. The official requested that Engert “kindly favor us with remittance to cover.” Further, the company staff member asked whether Engert would travel to London or Paris. There would be additional small fees depending on which city was his destination. In the top right-hand corner of the document, a handwritten note indicated that payment of the bill for $127.50 was sent on May 20, 1912.

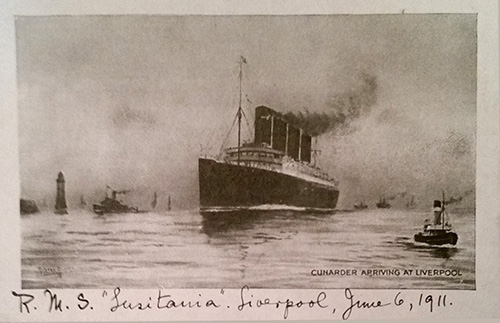

Box 12 folder 3 in the Engert Papers also contains a postcard depicting the Lusitania in Liverpool, England, dated June 6, 1911.

On May 7, 1915, a German submarine torpedoed and sank the Lusitania off the south coast of Ireland. Among those killed were 128 Americans. The ship was on its way from New York City to Liverpool, England. Many Americans reacted with outrage, and some clamored for U.S. entry into World War I. Although the ship was not armed, the Lusitania was carrying a load of 173 tons of shells and rifle ammunition when it was sunk. When the United States eventually entered the war on April 6, 1917, it listed unrestricted submarine warfare as one of its grievances against Germany.

Engert’s trip on the Lusitania must have been uneventful, as his granddaughter Jane Morrison Engert did not mention this trip in her biography of Engert entitled, Tales From the Embassy: The Extraordinary World of C. Van H. Engert (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2006).

Cornelius Van Engert became a respected authority on the Middle East. During his early years in Turkey, he transitioned to the rank of Consul. Over the course of his career, he held diplomatic posts in Cuba, El Salvador, Chile, Venezuela, China, Ethiopia, Iran, Lebanon, and Afghanistan. Engert’s last posting was as U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan from 1942 to 1945.

This document from the Cunard Company seems to indicate how Engert made his way across the Atlantic Ocean in 1912, as part of his journey to Turkey. The document acquired more historical significance and became more intriguing three years later in light of the sinking of the Lusitania.

--Scott S. Taylor, Manuscripts Archivist