September 26, 2023

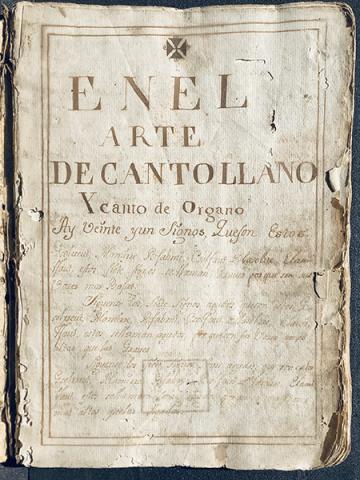

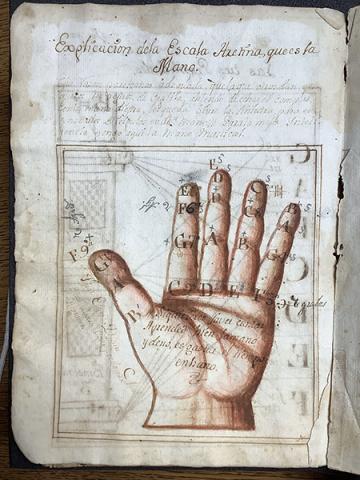

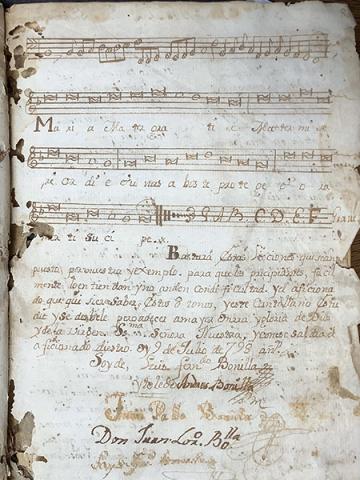

The small book displayed here is part of the Leon Robbin Collection of Music Manuscripts and Letters of Composers. Written in Spanish, probably in the 1750s, it appears to be an instructional manual written to teach basic musical theory, probably in an amateur or family setting, but it shows some peculiar features that make its exact purpose unclear. Among its diagrams is a “Guidonian” or “Aretinian” hand, a mnemonic device first developed by an Italian monk to teach his religious brethren choral singing some 700 years earlier. While prominent in the Middle Ages, musical theory and instruction had advanced significantly in the intervening 700 years, making its presence in this manual from the middle 1700s a little puzzling.

Guido of Arezzo was a Benedictine monk born shortly before the year 1000 C.E. and educated at the abbey of Pomposa, Italy. He quickly became known for his skill in training his fellow monks to perform the many chants and hymns they were required to memorize. Performance of the Daily Office and the Mass in the abbeys and cathedrals of the Church was the primary duty of priests and monks in the Middle Ages. But much of the Office and the Mass was sung, and the chants and hymns for both changed from day to day, meaning that monks and priests were required to learn thousands of chants in order to perform the liturgy of the Hours and the Mass. If you add the chants of the Office to those of the Mass, the historian Kenneth Levy has calculated that a monk would have memorized at least 75 hours of choral music, more than the music of Beethoven and Wagner combined.

Even though the Guidonian hand is not explained in any of Guido’s surviving works, he is so frequently credited with its development by later medieval music theorists that scholars believe he likely gave it the form and function we see here. It depicts three consecutive and overlapping hexachords (i.e., six-tone scales), starting with the thumb, continuing across the base of the fingers, up the pinkie, across the fingertips, down the index finger, over the middle to the ring finger, then back to the middle finger and up to its tip. While something simpler had been devised previously for a four-tone scale, it was not as elaborate or as detailed as Guido’s design. Although we don’t know exactly how the hand was used in practice, two methods seem possible: pointing out the various notes of a chant in the dim interiors of cathedrals and monasteries by pointing to various parts of the hand, and doing the same in monasteries in which vows of silence were the norm.

You might also be familiar with Guido’s other, more lasting innovation: musical staff notation, the most common way of visually describing music today. Other forms of musical notation preceded the version developed by Guido, but they could only indicate a note’s relative pitch to another. Guido’s landmark innovation was to create a visual scale where a specific position on the musical staff always indicated the same pitch, and where the intervals in pitch between notes are therefore specified precisely. In the medieval context, both the hand and the staff created more reliable and less time-consuming techniques than rote memorization to teach novice monks all those chants.

As for who wrote this particular manual of music, and why it includes these centuries-old instructional diagrams, we do not know. It has the names of multiple members of a Bonilla family inscribed inside its front cover and in the text itself, but we have not yet discovered their identities. The Guidonian hand and related diagrams might indicate that, more than a simple manual of musical instruction, this book may have also been trying to document the history of musical instruction itself.

We invite any curious student, staff, or faculty member with Spanish language skills–especially those with a musical background–to come examine the book and try to decipher its purpose and origins!

--Kevin Delinger, Robbin Music Collection Processor