"Washington Seminary, later renamed Gonzaga Hall, c. 1877"

Photographer unknown

Georgetown University Archives, School of Law Photographs

October 15, 2024

Students of Gonzaga College High School, the oldest all-boys high school in Washington, D.C., used the Georgetown University Archives to find out whether their institution had benefitted from slavery. Their findings that the Jesuits of Gonzaga were no different in their practices than those of Georgetown College have transformed the teachings of Gonzaga College High School.

Guest blogger Ed Donnellan, the social studies teacher who guided these students, explores the impact of this type of student engagement. Please consult with the online exhibition Slavery and Its Memory at Gonzaga College High School based on the findings of the student researchers

On April 30, 1822, a 14-year-old enslaved boy pulled weeds in the garden of the Washington Seminary, later renamed Gonzaga College High School. The image of this boy in the garden has remained with me since I first encountered it with my students in a 19th Century accounting ledger.1

Over the last year, as some American parents and politicians have argued that children might be traumatized by the facts about American history, I have often thought about that teenager and the journey my own students have been on.

This journey began in the fall of 2016 when Professor Adam Rothman, an historian at Georgetown University, came to speak to my students about the 1838 sale of 272 enslaved persons by the Jesuits. As the horror of Jesuit slaveholding became real to my students, one young man stood up and asked, “Did Gonzaga College High School have any connection to slavery?”

Rothman said he didn’t know. He challenged the students to search for the answer and suggested they visit the Jesuit archives located at Georgetown. The following summer a small group of Gonzaga students began searching for information. It was a search that would last three years and continues today.

The students came up with three essential questions they hoped their research could answer:

- Did the Washington Seminary, the predecessor of Gonzaga, directly or indirectly benefit from enslaved persons?

- Was Washington Seminary involved in any way with slave-run plantations?

- Did enslaved persons work at Washington Seminary?

Before the end of the first week, the student researchers would answer yes to each of these questions.

Like good investigators, they followed the money. The financial trail was most clear. On the same page that tracked incoming funds and expenses, an accounting ledger showed income from three of the plantations owned by the Jesuits — Bohemia, Newtown and St. Inigoes, totaling $3,200. That deposit is followed by an entry that shows $1,066.81 as an expense for "debt on purchase of ground on which Wash Sem is built."2 The connection was clear. Funds from Jesuit-run slave plantations generated income that financed the construction of the Washington Seminary.

Over time the students continued to discover links between Washington Seminary and the Jesuit slave-run plantations. The financial trail included payments to persons traveling to White Marsh, another Jesuit plantation, from the Washington Seminary. It included the delivery of food from St. Inigoes. In September, 1822, the founding president of the school, Anthony Kohlmann, S.J., was reimbursed “to defray his expenses to St. Thomas,” the last of the five plantations identified in the records by the students.3

As the boys shifted their focus towards that final question, they wondered, “Did enslaved persons work at the Washington Seminary?” This question would lead them to the darkest corners of American history.

The first clue was found in a line in the Washington Seminary accounting ledger from April 30, 1822: “To Gabriel for weeding in the garden during time of recreation…6 1/4 cents.”4

The students recognized that payments were routinely made to persons using their full names. Why didn’t Gabriel have a last name?

Two other small payments were made to Gabriel — one on October 14, 1824 and another on January 26, 1825. These payments were a form of tipping, a feeble attempt to soften the harshness of bondage.5

Just a few months after this final notation in the Washington Seminary ledger, Gabriel is discovered at Georgetown College where he has been leased to the school by Margaret Fenwick in return for a tuition discount.

The entry reads: “Mrs. Margaret Fenwick by Hillary’s wages from May 1, 1825 (Hillary arrived at the College about the end of April 1825) to the 13 of October 1827 (when Gabe a black boy from the Seminary of Washington took Hillary’s place) at $1.00 off a month.”6

In March 1828, Gabriel Dorsey entered into a self-purchase agreement with Margaret Fenwick, who claimed ownership of him. From I.A.A.1.d. Ledger, 1817-1832, Georgetown College Financial Records, p.1.

A year later, in March 1828, Gabriel, at the age of 20, was given a chance for self-emancipation. The terms were daunting:

Negro Gabe in the beginning of 1828 he obtained leave to buy himself free on the following terms; he has to pay $8.00 every month for his hire, and has besides to lay every month something aside until he collects of the sum of $400. which he has to pay for his freedom.

In April, 1828, Gabriel contributed $8 to this fund.7

At the time of this arrangement, Gabriel was owned by Margaret Fenwick, a prominent Catholic and mother of three Jesuits. She died On May 17, 1829. This change in ownership would be devastating for Gabriel.8

On June 20, 1829, a bill of sale records the purchase of Gabriel by representatives of Franklin & Armfield, the largest domestic slave trading firm at the time, operating out of an office on Duke Street in Alexandria. Two days earlier, an accounting ledger from Georgetown records a payment “to cash from Mr. Purvis for Gabe—$450.” Gabriel’s hope for freedom vanished.9

On November 26, 1829, after weeks spent at Franklin & Armfield’s slave pen, Gabriel was led in chains aboard the brig United States, headed to New Orleans. Gabriel’s full name appears on the manifest, Gabriel Dorsey, and his height was included, 5 feet, 3 inches.10

The final historical record for Gabriel is from December 5, 1829, when he arrives in New Orleans along with 33 other enslaved persons. The document reads, “Gabriel, a negro of light complexion age twenty one years, valued at seven hundred dollars.”11

Joshua Rothman, author of The Ledger and the Chain: How Domestic Slave Traders Shaped America, says this final record of Gabriel poses a challenge to contemporary Americans.

“Slaveholders and slave traders would have us reduce enslaved people like Gabriel to numbers on a page,” Rothman said. “It is our job to see past their focus on the money involved and remember the people behind the prices.”

Jennie K. Williams, of the University of California at Santa Cruz, said that “Gabriel and thousands of other enslaved Americans were forced to pay the toll of American geographic and economic expansion. It was a toll perpetually extracted, from moments of rupture from homes and loved ones, to confinement in cargo holds tumbling down the Atlantic, and throughout the entirety of lives spent in places that were never home.”

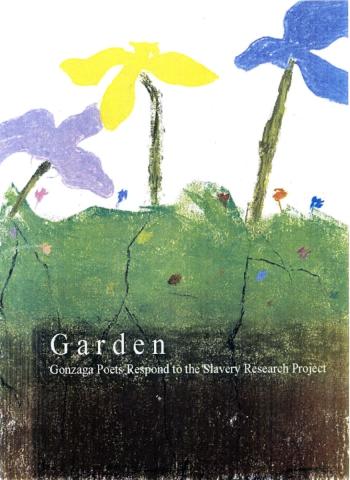

Joseph Fondriest (GCHS ‘19) and Marcus Stackhouse (GCHS ‘19) edited a volume of student poetry reflecting on Gonzaga's connections to slavery, Garden: Gonzaga Poets Respond to the Slavery Project (March 2018). An image depicting the garden that Gabriel Dorsey weeded was created by Joseph Wete (GCHS ‘19).

Booklet courtesy of Ed Donnellan, Gonzaga College High School

How does a school community grapple with such a painful past? I have found that the answer is to listen to our students. They have shown a willingness and an urgency to confront this complex, terrible history.

One student, Caleb Williams ‘21, while on a recruiting trip to Louisiana State University, met with Jessica Tilson, a direct descendant of those sold by the Jesuits in 1838, what is now known as the Georgetown 272. She took him to the Immaculate Heart of Mary Cemetery in Maringouin, Louisiana where several persons sold by the Jesuits are buried. He listened to the stories of the descendants and came back to Gonzaga with a special gift. He handed me a small jar with soil taken from the land. I keep the jar on my desk as a reminder of this history.

While sitting in on student-led discussions, I have listened to my students express anger and outrage that this history was kept from them for so long. They yearn to confront this history. They are drawn to the story of Gabriel, who was their age when he was enslaved at the school they attend. They have written powerful poetry in response to the research. Poetry offers students a unique way to confront this history.

In November 2023, students marked the 200th anniversary of the sale of Gabriel Dorsey by marching from the site of the Franklin & Armfield holding pen, now Freedom House, to the Alexandria harbor, where he boarded a ship to New Orleans. Photograph courtesy of Ed Donnellan.

Last November a group of Gonzaga students traveled to Freedom House, the former site of the Franklin & Armfield slave office. The students wanted to see where Gabriel was held after his sale by the Jesuits. After touring the museum the students prepared to walk silently down Duke Street to the Potomac River waterfront, where Gabriel was put on a ship and sent to New Orleans. Each student held in their hand the name of an enslaved person who accompanied Gabriel as they were put on the brig, The United States. At the waterfront the students read each of the thirty three names, and responded, “We remember” After the litany of the names was read several students recited poetry that was written in response to the research. The gathering concluded with inspiring words from Julie Hawkins Ennis who is a descendant of the 272 persons the Jesuits sold in 1838. Walking the same path as Gabriel was an unforgettable experience.

Students can and must learn this history. They only ask that we tell the truth. Thanks to their classmates they now know the truth about Gonzaga College High School’s history with slavery. We are all better for it.

By Day

I dug through dirt

You smelled the flowers

I wiped soiled tables

You sat and laughed

I was tipped

You were entitled and gifted

I prayed, you prayed

The garden grew

I could not

Joseph Wete ‘19

Notes

- Washington Seminary Account Book and Journal, 1821 - 1827, Gonzaga College High School/Washington Seminary Collection (GCHS/WS Collection), Georgetown University Archives (GUA), April 22, 1822, box 1, folder 2.

- Statement of Finances, March 5, 1821, Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu (ARSI), Maryland-1002-II_0241. By permission of ARSI.

- Washington Seminary Account Book and Journal, 1821 - 1827, GCHS/WS Collection, GUA, October 29, 1822, box 1, folder 2.

- Washington Seminary Account Book and Journal, 1821 - 1827, GCHS/WS Collection, GUA, April 22, 1822, box 1, folder 2.

- Washington Seminary Account Book and Journal, 1821 - 1827, GCHS/WS Collection, GUA, October 14, 1822, and January 26, 1825, box 1, folder 2.

- I.A.2.c, Journal E, 1821 - 1831, Georgetown College Financial Records (GCFR), GUA, p. 258; “The College exchanges Hillary for Gabe, 1827,” Georgetown Slavery Archive (GSA).

- I.AA.1.d, Ledger, 1817 - 1832, GCFR, GUA, p.31; “Gabe obtains ‘leave to buy himself free,’ 1828,” GSA.

- Deaths, 1818-1867, Holy Trinity Church Archives, Digital Georgetown, May 17, 1829.

- I.A.3.f, Cash Book, February 1, 1825 - March 1, 1832, GCFR, GUA, June 18, 1829.

- Slave Inward Manifests, National Archives and Records Administration.

- Notarial Archives of New Orleans.