In our visual culture, nuns are a potent symbol of religion. From the Madeline children’s books (1939) to The Sound of Music (1956) and American Horror Story: Asylum (2012–2013), nuns have permeated popular culture. In the dawn of the Second Vatican Council (1962), the role of nuns in modern society was debated and differed from diocese to diocese. These debates brought a significant amount of attention to the way we see nuns in the everyday world. Photographs of nuns using the telephone feel almost like a juxtaposition of modern technology and an old world vocation. Several photographs in the Perry Collection focus on nuns prior to and just after the Second Vatican Council.

To think of nuns is to think of cloisters. Nuns were traditionally kept in the cloisters of their monastic institution. The women separated themselves and when they received a rare visitor, they were separated by a grill or barrier. It was only until the twentieth century that nuns started participating in evangelizing in Europe and leaving the convent walls. On the other hand, in America, it was more common that nuns act as nurses (such as the many nuns that helped tend to the wounded in the American Civil War) or teachers in primary and secondary school.

Ilse Bing was one of the many photographers fascinated by the life of early twentieth century nuns. Born to a Jewish family in Germany, Bing started her career studying Art History. She purchased her Leica in 1929 three years after the Leica was first introduced, and moved to Paris. By 1932, she was known as the “Queen of Leica.” It is unclear how and why Bing gained such a close relationship to the nuns of Paris, particularly as her photographs at the time focused on Paris fashions. Bing and her husband were able to flee France in 1941 as their visas were sponsored by the fashion editor of Harper's Bazaar. When her photographs arrived in the U.S. after the war she could only keep a limited number due to the high customs fee.

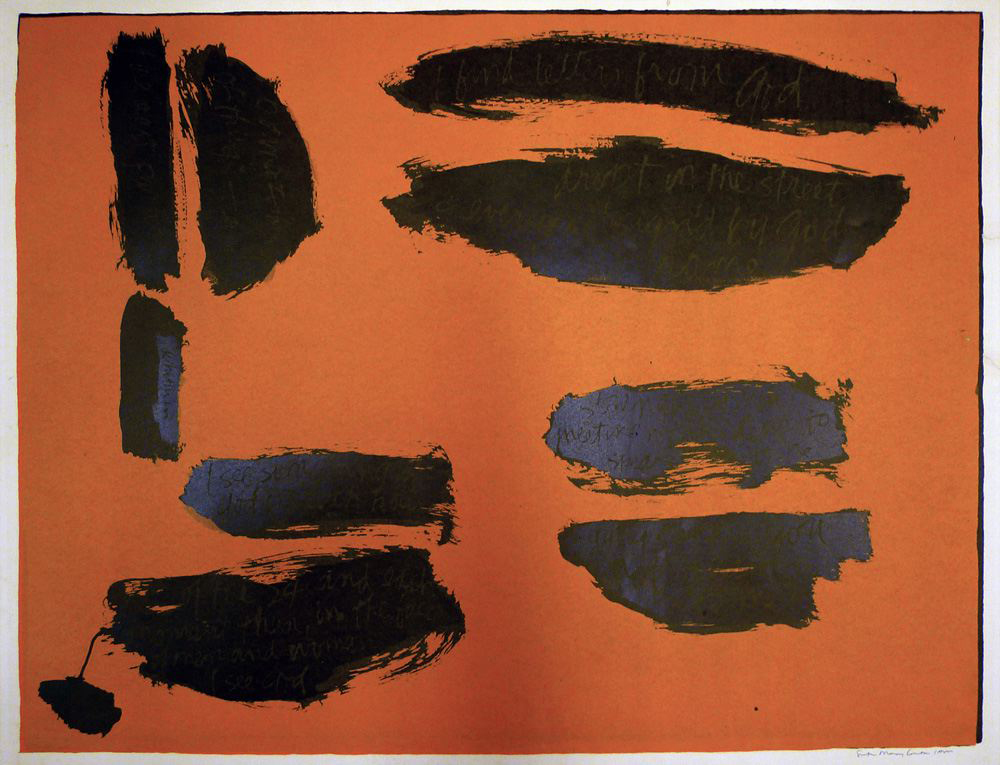

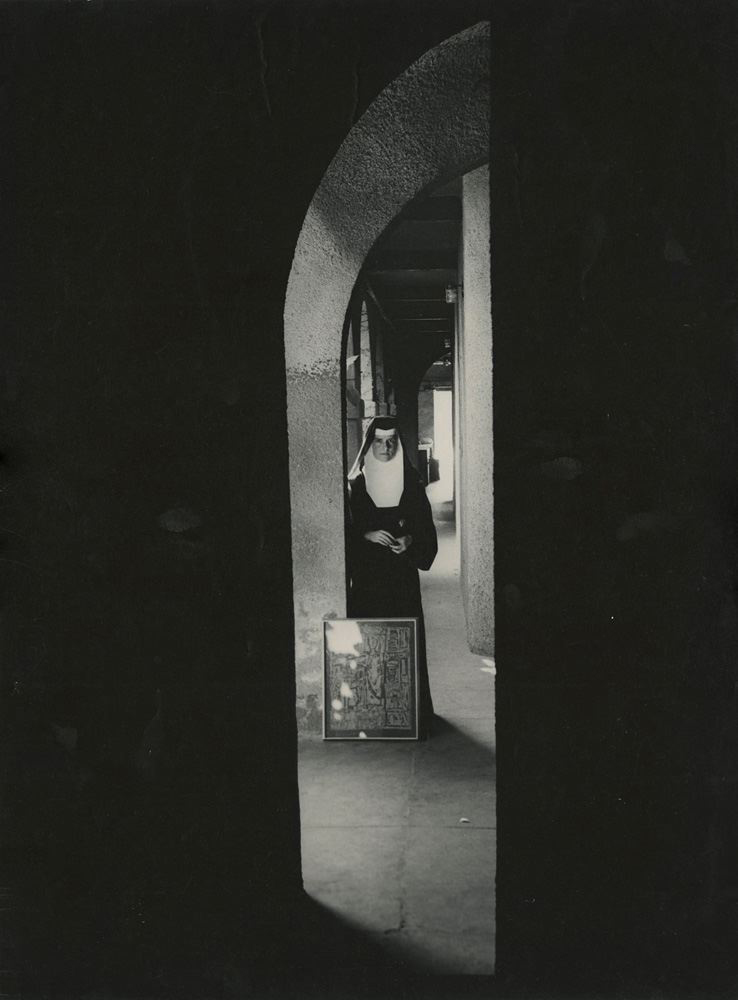

Nuns were not just the subject of art, but nuns were also artists. Largely unknown to the public, nuns also participated in illuminating manuscripts like their male counterparts. These illuminations by nuns for nuns are called Nonnenarbeiten (German: Nun’s Work). In Spain, nuns could waive their dowry if they were accomplished musicians or artists as they were seen as receiving help from God.[i] Sister Corita Kent, represented with one of her works in the Lowe photograph, joined the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles in 1936. She became a well-known artist during the Pop-Art movement in the 1950s and 1960s and taught at the Immaculate Heart College. Corita had an affinity for Chinese and Irish calligraphy and added calligraphy to her work to show the power of the written word to create new images. She was also significantly influenced by the Abstract Expressionist Robert Motherwell.

By the 1950s, the Catholic Church became wary of the image of nuns’ habits. Particularly, Pope Pius XII was concerned that the flowing robes were unhygienic and thought that cleaning the robes would take too long. The head cornette was abandoned in 1964 as part of the sweeping aesthetic changes made by the Second Vatican Council. Part of the call to modernize the nun aesthetic was to appeal to teenage girls who were the target demographic.[ii] The Second Vatican Council also drew attention to the politically active nature of Nuns. Nuns answered Martin Luther King Junior’s rallying call, marching with and protecting protestors in Selma, Alabama. Moreover, many nuns were arrested for protesting against the Vietnam War.

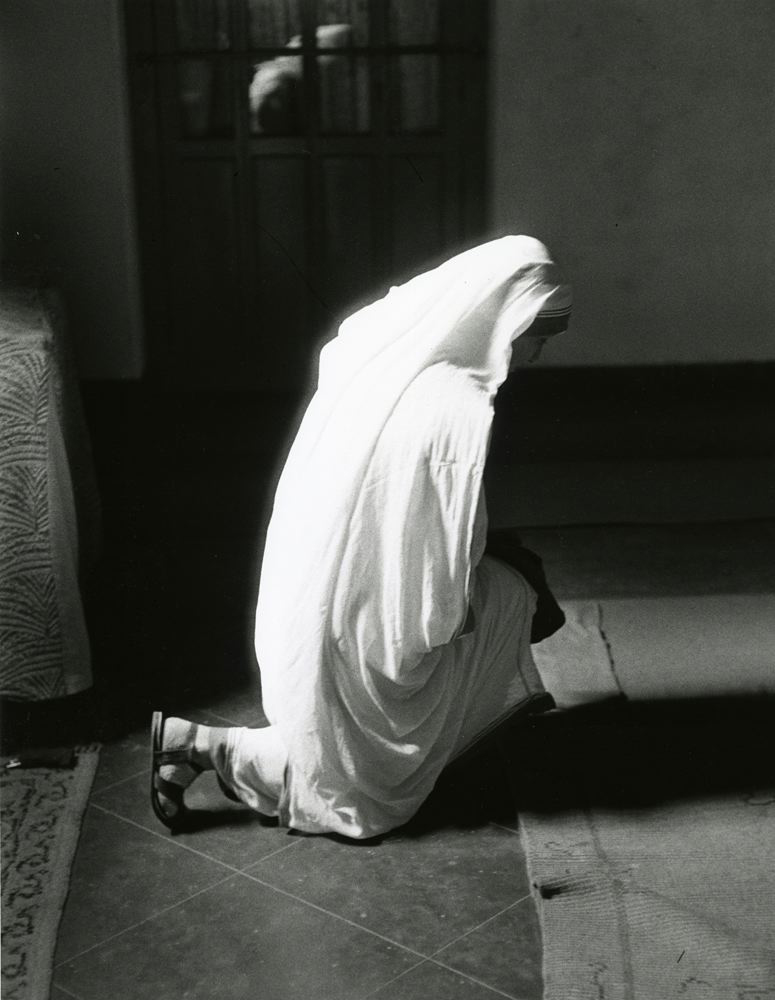

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Mother Theresa became the most well-known nun and was the face of the Modern Sisterhood. She was awarded the Noble Peace Prize in 1979 for her missionary work in Calcutta. There she had established a free hospice and allowed people to die in accordance with the last rights of their own faith, such as being given water from the Ganges or read the Qur'an. Eleven years after her death, she was canonized in 2016. She is one of the thirty-five saints that were nuns in their lifetime.

Note [i] Taggard, Mindy Nancarrow. "Art and Alienation in Early Modern Spanish Convents" in South Atlantic Review 65, No. 1 (2000): 24-40. doi:10.2307/3201923.

Note [ii] Sullivan, Rebecca. Visual Habits: Nuns, Feminism, And American Postwar Popular Culture, University of Toronto Press, 2005. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/georgetown/detail.action?docID=4672230.

Katie O’Hara, University Art Collection Curatorial Intern and Graduate Student in Art and Museum Studies (Fall 2018)