February 16, 2023

At the end of 2022, Archivist Cassandra Berman hit an exciting milestone: she completed the reorganization of the Maryland Province Archives and finished a new finding aid to guide researchers in using the collection. In this post, she reflects on her experience working with the archives, and discusses how the new finding aid will make the collection more accessible to a diverse range of researchers. Those interested in the collection should also view an online exhibition of materials curated by Mary Beth Corrigan.

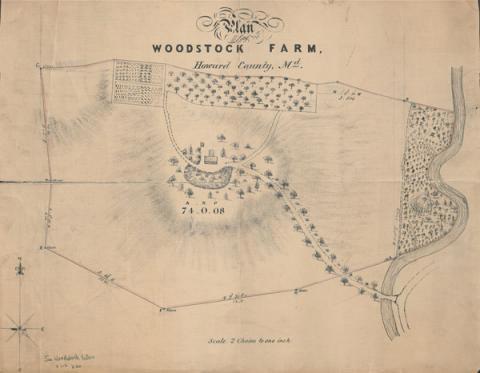

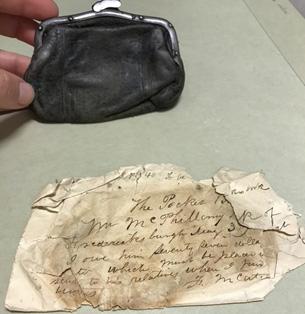

When I arrived at Georgetown as the new Archivist for the Maryland Province Archives, I knew that the collection I was hired to care for was an important one. Formally known as the Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus, the materials document almost 400 years of Jesuit life in the mid-Atlantic region. The records are entwined with the foundation of Georgetown College, and they help tell the story of Catholicism in North America. Most significantly, for the purposes of my work, the collection reveals the Jesuits’—and Georgetown’s—deep ties to slavery, the exploitation of enslaved people, and the sale in 1838 of 272 individuals who lived and labored on Jesuit plantations, the profits from which helped Georgetown transform from a struggling college into a thriving institution.

I also knew that Georgetown was one of several universities in the United States whose complex ties to slavery were finally starting to be untangled, thanks to the tireless work of students, journalists, scholars, and especially the descendants of enslaved individuals who had helped bring these painful histories to light. And it was clear that my main objective in reorganizing the Maryland Province Archives was to contribute to Georgetown’s, and the Jesuits’, efforts to make their deeply troubling pasts more transparent.

What I could not have known before diving into the materials, however, was just how much work had already been put into the collection. I discovered that many of the documents in the Maryland Province Archives had been described, sometimes in great detail, since the early 1900s by Jesuit administrators and archives staff. That a dedicated team of graduate students, led by Dr. Adam Rothman of the Georgetown History Department, had made key slavery-related documents in the collection available to researchers through the Georgetown Slavery Archive. That decades of work had been put into the Jesuit Plantation Project, which tracks relationships between enslaved individuals and slavery-related events. Or that a graduate student, Elsa Mendoza, was in the later stages of a dissertation examining how enslaved laborers and Catholic slave owners profoundly shaped Georgetown as an institution.

What, then, would be my role as caretaker of the high-profile Maryland Province Archives? This wasn’t a hidden collection, to be sure; most of the materials had, at least nominally, been accessible to researchers for decades. I realized fairly quickly, however, that too much information can actually be a hindrance. The existing finding aid was hundreds of pages long; for an undergraduate student or inexperienced researcher, this could easily be overwhelming. And while certain aspects of the collection related to prominent Jesuits were described carefully, materials pertaining to slavery and race relations received too little attention, and suffered from inconsistent description that did not conform to professional archival standards.

So, inspired by the principles of reparative archival description—an effort to create more inclusive finding aids by amplifying the experiences of those long sidelined in the archives—I got to work. My colleague Mary Beth Corrigan proposed a streamlined organization for the collection, sensibly based on Jesuit administrative structure. I integrated 90 boxes of Province records known as the “Addenda”—many of which had not previously been available to researchers—as well as 20 boxes of documents concerning the Maryland Province that had originally been part of Georgetown’s University Archives.

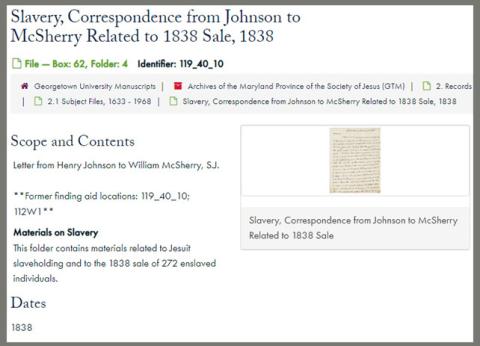

In the finding aid, I created a “Materials on Slavery” designation so users could easily identify and access all 172 folders that contain documents related to Jesuit slaveholding. I worked with Digital Production Coordinator Theodore Mallison, who is ensuring that all materials created before 1900 are digitized, and that these high-resolution digital images are linked directly to the online finding aid and include all relevant metadata—meaning they will not get lost on our digital platform, devoid of context. (The digitization of the Maryland Province Archives, well underway, will be completed later this year.)

I attended to preservation concerns, re-foldering and re-boxing all materials. I wrote new, more consistent folder labels, corrected dates, and separated restricted and oversized documents. As I reorganized documents, folders, boxes, and series, I kept track of where everything had been housed before, and then integrated this information into the finding aid—so that researchers working off of older citations would still be able to find what they needed.

The result? The Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus is now a collection totaling 292 archival boxes and 14 card catalog drawers. The online guide to the materials is streamlined into ten navigable series. Digital images of the documents themselves are (or will soon be) linked to all materials created before 1900. Descriptions reference the Georgetown Slavery Archive, enabling researchers to find slavery-related documents even if they have come to the finding aid from another platform.

Screenshot of a folder displayed in the new finding aid.

Of course, I like to think that we have gotten a lot right with this detailed, and sometimes painstaking, reorganization project. But, surely, there will always be room for improvement; researchers come from a range of backgrounds, the collection is vast, and archivists simply cannot anticipate all user needs and questions. We are also constantly learning about the impact of the language we use to describe archival materials, and researchers alert us, not infrequently, to their important finds related to slavery and other subjects as they pore over letters, diaries, maps, and financial accounts more closely than we are able to ourselves.

I believe that the process of reorganizing such a vast collection of materials has made us realize that our work with the Maryland Province Archives—indeed, with all collections that illuminate the horrific and often sidelined histories of slavery—cannot ever really be considered “done.” Just as the implications of slavery are still with us, so too must be the drive to make this history more accessible.

—Cassandra Berman, Archivist for the Maryland Province Archives