March 19, 2021

In celebration of Women's History Month, Mary Beth Corrigan introduces us to two sisters who helped build a nurturing community for the Black congregation, free and enslaved, of Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Georgetown.

The Jesuits of the Maryland Province viewed the people enslaved by them both as a source of capital and as souls that they needed to save. It is now well known on the Georgetown University campus that this twisted view of the humanity of the enslaved led to the Jesuit General’s sanction of the 1838 sale of more than 272 people, on the condition that families be kept together.

Regardless, Black people remained a vital part of the Roman Catholic Church in the Washington D.C. area. Embedded within the Holy Trinity Church Archives is a partial explanation for this persistence, at least in Georgetown. Its earliest records reveal the leadership of sisters Liddy and Lucy Butler in the creation of a community of Black women who used the rites of the Catholic Church for their own purposes, specifically to help mitigate the impact of enslavement upon their families.1

Liddy and Lucy Butler probably arrived in Georgetown shortly after they were manumitted between 1790 and 1792. They were members of the well-known Butler family, who had successfully sued for their freedom by proving their descent from a white indentured servant named Nell Butler. The Butlers were one of several families who, with the backing of the Maryland Society for the Abolition of Slavery, challenged the legal basis of their freedom and threatened the wealthiest members of the Maryland gentry, including the Jesuits who had established Georgetown.2

William G. Thomas and his team of researchers at the University of Nebraska Lincoln have created “O Say Can You See: Early Washington D.C. Law & Family,” a site that includes a digital collection of petitions for freedom, supporting documentation, and judgments. That collection provides some information on the background of Liddy and Lucy Butler. Of the cases filed by members of the Butler family, there was only one instance of women named Liddy and Lucy claiming the same mother, Elizabeth Butler who had eleven children in total. They had experienced the familial separations so common among enslaved peoples, collectively they sued nine different owners located in St. Mary’s, Charles, and Washington Counties. (Three of Elizabeth’s children were part of the suit against her owner Henry Hill in St. Mary’s County).3

Several of the Butlers formed a community with their siblings and extended family in Georgetown. Many became active members of Holy Trinity Catholic Church. Liddy and Lucy Butler stand out in the records, bringing enslaved and free Black people into that religious community. Liddy first appears as a godparent (listed as a sponsor) of the Baptism of Mary Ann Adams, the daughter of Liddy Adams, a free Black woman of “St. Mary County now in Georgetown.”4 Liddy and Lucy Butler took on the critical role of godparent during Baptismal rites numerous times during the first 30 years of the parish. Holy Trinity Church historian William Warner has identified Liddy as godmother for 38 children and Lucy for 27 children. In looking at the entire extended family, Warner maintains that the Butlers served as godparent for approximately one out of every three Baptisms among Black people. Warner credits Liddy and Lucy for their partnership with the priests of Holy Trinity in promoting its Black membership. That membership accounted for approximately one third of the entire congregation until the Civil War.5

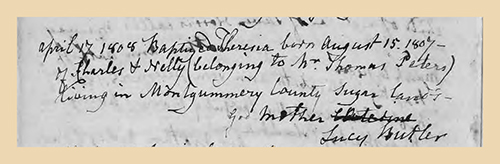

On April 17, 1808, Charles and Nelly designated Lucy Butler

as the godmother of their 16-month-old daughter Theresa.

The parents and child were enslaved by Thomas Peter, who

owned a plantation in Sugarlands in Montgomery County.

In 1805, Thomas Peter had constructed Tudor Place

as the urban mansion for his family. It is now a house

museum on 1644 Q Street, N.W.

From the Baptismal Register, 1805-1845, Archives of the Holy Trinity Catholic Church, p. 29.

Liddy and Lucy Butler both reflected longstanding communal practices and helped shape them in ways these numbers do not reveal. Godparentage was the domain of women within this Black congregation. White parents almost always named both a godmother and a godfather, whereas Black parents frequently designated one or two women with the critical role of supporting the religious education of the child and finding “a good and virtuous nurse,” in the event of the death of parents or the sale of a parent.6 Free and enslaved people participated in the Baptismal rites, reflecting the acceptance of enslaved Blacks within the Black community. For example, on April 20, 1797, Lucy sponsored the Baptism of Richard, the son of Sarah who was enslaved by prominent Scottish merchant Robert Peter of Georgetown.7 Sarah presented her son Richard for Baptism without the participation of his father. It was not unusual for the Butler sisters to sponsor the Baptisms of children without the presence of their fathers. On April 12, 1798, they both served as godmothers for the Baptism of Stephen and Francis Butler, the son of Henny, without the participation of his father.8 Nearly two out of every five Baptisms performed for black children before 1830 were presented by their mothers without the participation of their fathers, a rate far higher than those presented by white parents. This high incidence of non-participating fathers reflects in part the secondary role of men in Catholic rituals generally. It is also possible that an enslaved mother might hide the identity of a Black father lest he be objectionable to the mother’s owner, or in Georgetown without license from his own owner. The other possibility is that the Black mother was concealing the identity of a white father who forcibly coerced her into a sexual relationship.

Confirmation Register showing the participation of

teenaged Black women in the rite that signalled

their commitment to religious education and practice.

The sacrament was performed by Archbishop Samuel Eccleston

of Baltimore on November 26, 1837.

From the Baptismal Register, 1835-1858 Archives of the Holy Trinity Church, p. 431.

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of the community centered upon women and children which Libby and Lucy Butler helped to create. The rite of Baptism conferred a social legitimacy to the parent-child relationship that did not exist in the law. Black family and community members could formalize obligations to protect each other’s children in the event of slave trade or death of a parent. Baptismal rites also implied the recognition of family relationships, particularly the parent-child relationship, by the broader congregation, one that included the people who enslaved them or other community members.

The 1838 sale shows that this recognition could be brazenly disregarded, even by those priests who administered the sacrament of Baptism. However, while Black people feared sale above all, other routine decisions by others could also potentially disrupt the parent-child relationship. Enslavers established work schedules and set parameters on “off” hours, thereby limiting the time that parents could spend with their children. The limited recognition of the parent-child relationship conferred by Baptism strengthened the position of Black mothers seeking the space from their enslavers to properly raise their children. By standing as godparent to so many in the community, Liddy and Lucy helped the Black people of Georgetown use Holy Trinity Church for their own purposes. They helped create a model followed by other Black women who became the heart and soul of Trinity’s Black congregation.

--Mary Beth Corrigan, Curator of Collections on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation

Notes:

1. Parish histories recognize the importance of the Butlers: William W. Warner, At Peace with All Their Neighbors: Catholics and Catholicism in the Nation’s Capital, 1787-1860 (Washington: Georgetown University Press, 1994), 89-92; Bernard Cook, “Holy Trinity History, Part IV: The Butler Sisters,” Holy Trinity Church, accessed March 17, 2021.I first began my own research of the Black community within Holy Trinity Church parish in the 1990s. See “A Social Union of Heart and Effort: The African American Family on the Eve of Emancipation” (Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Maryland College Park, 1996) and “Making the Most of an Opportunity: Slaves and the Catholic Church in Early Washington,” Washington History 12:1 (Spring/Summer 2000), 90-101. Accessed March 17, 2021.

2. Her children with the defendants listed parenthetically were Joanna (Mary Boarman of Charles County), Lydia (James Carrico of Charles County), Lydia (Nicholas Swingle of Washington County), Augustus ‘Gustavus’ (William Thomas of St. Mary’s County), Chloe (Nicholas L. Sewall of St. Mary’s County), Clara (Patty Shade), Ignatius (William Craik of Charles County), Lucy (Benedict Wheeler of Charles County), Jerry (Henry Hill of St. Mary’s County), Jess (Henry Hill of St. Mary’s County), and Phillis (Henry Hill of St. Mary’s County). See the visualization of the Butler family and the links to the document transcripts of the legal cases provided by OSCYS, “Butler Family Network,” O Say Can You See, accessed March 17, 2021.

3. William G. Thomas argues that the freedom suits filed by the Butlers, Mahoneys, and Queens threatened the underpinnings of slavery in Maryland. He explores especially the freedom suits filed by the Mahoneys and Queens against the Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen. On the Butlers, see William G. Thomas, A Question of Freedom: The Families Who Challenged Slavery from the Nation’s Founding to the Civil War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 24-27. Eleanor Nell Butler had married an enslaved man, Charles, just as the laws regulating slave families were changing in Maryland. By the terms of a 1664 law, she assumed the enslaved status of her husband so that they would, in turn, pass on that status to her children. Shortly after her marriage, Maryland law changed, providing that the mother’s status determined that of her progeny. Even though Nell’s children had yet to be born, the new law did not apply to Nell and her children. Her descendants waited, looking for the opportunity to sue for their freedom. In 1787, Mary Butler won her case against her enslaver Adam Craig. After he lost his appeal in 1791, the descendants of Nell Butler, the extended family of Mary, sued for their freedom.

5. Warner, William, At Peace with All Their Neighbors, 91.

6. Collet, Peter, Doctrinal and Spiritual Catechism (New York: B & J Sadler, 1853), 155-156.