Born in the Netherlands, Margaretha Geertruida Zelle (1876-1917) traveled to Java, Indonesia, at age 18 in response to an advertisement for marriage placed by army captain Rudolf MacLeod. Two children ensued; however, the marriage foundered and ended in divorce in 1907. Zelle sought solace and escape from domestic circumstances by immersion in Indonesian culture, especially traditional dance forms. By 1897, she had joined a local company.

In 1903, Zelle moved to Paris where she performed on horseback and supplemented her income by posing as a model for artists. Zelle’s specialty became exotic dancing, inspired by her training in Indonesian dance. Influential contemporaries in dance included Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, both significant figures in 20th-century modern dance which found inspiration in Asian and Egyptian cultures. In 1905, Zelle was invited to dance for Émile Guimet, owner of an oriental art museum. Guimet encouraged Zelle to adopt a more evocative stage name than Lady Gresha McLeod, the one she had been using. As early as 1897, she had written to a friend that she wanted to dance under the name Mata Hari, a Malay phrase for “sunrise.” Mata Hari made her debut at the Musée Guimet to a select audience, causing a sensation, not least of all because her performance included dancing nude.

During World War I, Zelle traveled freely across borders due to the neutrality of the Netherlands. Unfortunately her movements drew attention, and in 1916, en route from Spain to England, she was detained by Scotland Yard for questioning by Sir Basil Thomson, who was in charge of counter-espionage. Zelle was eventually released. In 1917, radio messages between Madrid and Berlin reporting on activities of a German spy, codenamed H-21, were intercepted by French intelligence which identified the spy as Mata Hari. Zelle was arrested in her room at the Hotel Plaza Athénée in Paris. She was accused of spying for Germany and causing the deaths of fifty thousand soldiers. She was tried, found guilty of treason, and executed by firing squad on October 15, 1917.

In 1985, official case documents, which were to remain sealed for a hundred years under the authority of the French Ministry of Defense, were opened at the behest of biographer Russell Warren Howe. He was able to reveal that Zelle was innocent of the charges of espionage. Her body was never claimed by any family members, and was accordingly disposed of for medical study. Her head was embalmed at the Museum of Anatomy in Paris; however, in 2000 archivists discovered that the head, as well as other body parts, had disappeared without record. The Frisian Museum in Zelle’s native town of Leeuwarden exhibits a Mata Hari Room and is dedicated to collecting research materials on her life.

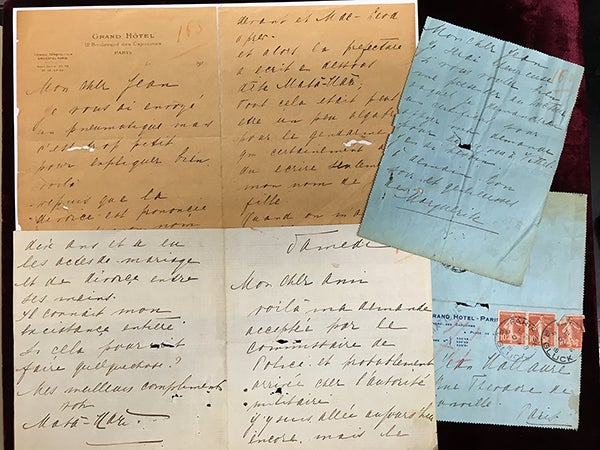

Shown here are letters written by Zelle to Jean Hallaure, requesting assistance for safe passage to Vittel, a spa that Zelle frequented. Hallaure was a second lieutenant in the Deuxiѐme Bureau (the intelligence branch) of the French Ministry of War, with whom Zelle was romantically involved and who was ultimately responsible for Zelle’s arrest. Biographer Pat Shipman vividly recounts this episode in her book Femme Fatale: Love, lies, and the unknown life of Mata Hari (2007).

All are welcome to see the Mata Hari letters located in the Miscellaneous Manuscripts Collection GTM.Gamms430, Box 3.

Lisette Matano, Manuscripts Archivist

June 24, 2016