Among its extensive collections documenting the history of the Panama Canal, the Booth Family Center for Special Collections contains the John L. Stephens–Henry Chauncey collection. That particular collection includes 15 letters from Stephens to Chauncey concerning the construction of the Panama Railroad, the world’s first transcontinental railroad and the precursor of the Panama ship canal. Stephens and Chauncey were business partners in the Panama Railroad venture, and their correspondence sheds light on the planning and building of the railroad.

The concept of joining the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean was a long-standing dream. Because the distance between the oceans is relatively small on the Isthmus of Panama, many people looked for a route in that area. Although several sites were studied, Stephens and Chauncey selected the Isthmus of Panama as the most viable option. Interest in the Panama route between the seas rose when gold was discovered in California in 1848. If somehow the oceans could be connected, a favorable route could be made across Panama, saving time to the California gold fields and replacing the long ship route around the tip of South America or the arduous land route over the American west. In January of 1849, a group of prospectors successfully traversed the Isthmus of Panama through a combination of mule, canoe, and foot travel.

On April 21, 1849, John L. Stephens, the first president of the Panama Railroad Company, wrote a letter to his business partner Henry Chauncey about the construction of the Panama Railroad. The letter is preserved in box 1 folder 2 of the Stephens-Chauncey collection. Stephens began on an optimistic note:

Judging from the conversation between us this morning in walking up Broadway, that you look upon our Rail-road project as weighty and burdensome, I am induced to throw upon paper my views for carrying it out, which if I am not grossly in error make the whole matter simple, and easy of accomplishment.

Stephens described the initial steps in creating a railroad across the Isthmus of Panama:

We have, as you know ordered a steamer, which will navigate the Chagres river up to the point where our road will cross the river on its way from Panama to Navy Bay. From that point, I would build a horse rail road to the Bay of Panama, distance about twenty miles. The steamer will cost ten or twelve thousand dollars; the road about $10000 per mile. Three hundred thousand dollars or thereabouts would probably give us a communication which would satisfy all the wants of the travelling public, and would transport quite as many passengers, as if we had a rail road through, costing $3.000.000…. A communication of this kind could probably be put into full operation by the end of … June 1850.

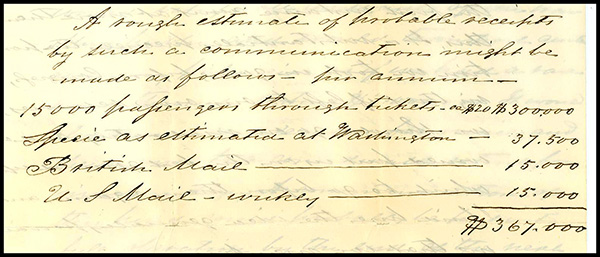

In his letter, Stephens calculated the proceeds of a horse rail road.

Stephens closed his letter by saying, “I am sure that if we will go on with the same spirit, and cordial cooperation with which we began and will be content with feeling our way, the whole will result successfully, and most creditably, for all concerned.”

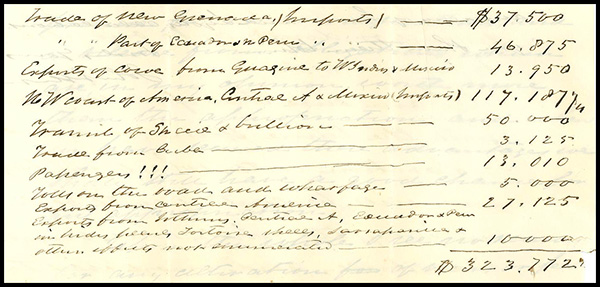

In the postscript, Stephens listed estimated receipts for a macadamized road across Panama as calculated by Mr. Lewis, British Vice Consul of Panama in February 1845. That particular prediction was made before the California gold rush.

In 1850, construction actually began on the Panama Railroad. Construction workers battled malaria, cholera, yellow fever, smallpox, and extreme heat. For his part, John L. Stephens died of fever in 1852. When it finally opened for business, the Panama Railroad covered 47 ½ miles from shore to shore. The Panama Railroad was built in 5 years at the cost of $8 million1. When it was eventually built, the Panama Canal followed essentially the same path as the railroad.

Scott Taylor, Manuscripts Archivist

October 28, 2016

1David McCullough, The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1977), 35.