Most people have heard of Washington Irving (1783-1859), the prolific American author who penned such classics as “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle.” However, few realize that he had a distinguished career as a U. S. diplomat. The Booth Family Center for Special Collections owns a letter book documenting Washington Irving’s work as U.S. Minister to Spain from 1842 to 1846. The letter book is a bound volume containing handwritten copies of outgoing letters sent by Irving to American and Spanish diplomats.

Irving spent the years 1815 to 1832 in Europe, where he was one of the first American writers to garner widespread international acclaim. At the invitation of U.S. Minister to Spain Alexander Hill Everett, Irving became an attaché in the U.S. embassy in Madrid in 1826.[1] He became fascinated with Spanish culture. publishing the History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus in 1828, the Chronicle of the Conquest of Grenada in 1829, and The Alhambra in 1832. He continued his diplomatic career as a secretary in the U.S. legation in London from 1829 to 1832.

Irving returned to Spain as the U.S. Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary from 1842 to 1846. He once again put his literary skills to good use by writing detailed, insightful dispatches, vividly describing the tumultuous state of contemporary Spanish politics. Political unrest surrounded 12-year-old Queen Isabella II (1830-1904). Her opponents questioned her right to the throne at such an early age, and they criticized her regent. Irving felt sympathy for the queen, who remained in power despite serious challenges.

Amidst the political turmoil, Irving found some moments to continue his writing pursuits. Poor health and a skin condition, however, kept him away from his duties at times. During this period, he also made some trips to other parts of Europe for his health.

A number of letters from U.S. Minister to Spain Washington Irving to U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster are preserved in our letter book. Here are excerpts from a November 22, 1842 dispatch to Webster detailing an insurrection in Barcelona.

Irving reported that “sudden news arrived of a formidable insurrection at Barcelona.” He analyzed the source of the uprising:

The immediate cause of this outbreak appears to have been accidental; but the populace of Barcelona, at all times excitable, have of late been in a general state of uneasiness and irritation, caused, it is said, by the rigorous hand held over them by Government; by the rough, and at times unconstitutional, measures of General Lurbano in suppressing sedition, contraband, and robbery; and by the apprehended “Cotton Treaty” with England.

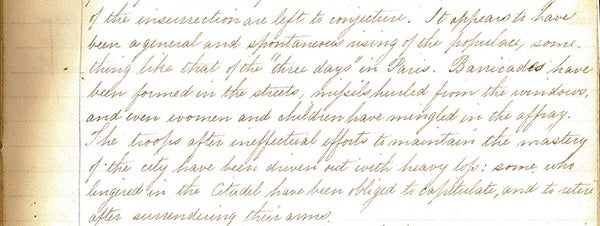

He provided even more detail:

It appears to have been a general and spontaneous rising of the populace, something like that of the “three days” in Paris. Barricades have been formed in the streets, missils [sic] hurled from the windows, and even women and children have been mingled in the affray. The troops after ineffectual efforts to maintain the mastery of the city have been driven out with heavy loss; some who lingered in the Citadel have been obliged to capitulate, and to retire after surrendering their arms.

He noted how the revolt may affect the Queen:

Yesterday [General Baldomero] Espartero [the Queen’s Regent] took his leave in military style of all of the National Guards, assembled in the Prado. He made an address professing his determination to maintain the constitution of 1837, against despotism on the one hand, and anarchy on the other, and he confided as on a former occasion to their patriotism, loyalty, and valor, the protection of the city and of the youthful Queen. His address was received with animated acclamations, and he departed amidst the cheerings of the multitude.

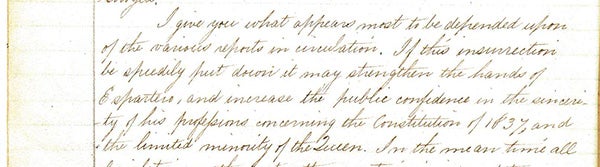

Irving concluded his analysis by writing:

I give you what appears most to be depended upon of the various reports in circulation. If this insurrection be speedily put down it may strengthen the hands of Espartero, and increase the public confidence in the sincerity of his professions concerning the Constitution of 1837, and the limited minority of the Queen.

Washington Irving brought his unique literary perspective to his work as U.S. Minister to Spain. He was an astute observer of Spanish politics. Although this letter was written in a secretary’s hand, it and others like it found in Washington Irving’s letter book from Spain provide ample source material of his time in Spain and his contributions to U.S. diplomatic history.

--Scott Taylor, Manuscripts Archivist

January 31, 2017

[1] The Booth Family Center for Special Collections also holds the Alexander Hill Everett collection, a small collection of documents by Alexander Hill Everett.