[p. 229]

Freedom of Religion

I. The Ethical Problem

JOHN COURTNEY MURRAY, S. J.

Woodstock College

The problem of freedom of religion could be approached either from an historical or from a theoretical standpoint; and from this latter, one could survey either the situations that existed in the past or those that prevail at the moment; and these latter situations could be studied either in themselves or in their historical roots. We must, therefore, ask the initial question, where should the discussion of this problem begin? I believe that the initial standpoint must be that of theory. This is true of Catholic discussions, especially those that aim at conveying to our Protestant and Jewish brethren some understanding of our position. It is equally true of Protestant discussions that wish to be universally understood; they must begin with a clear statement of theory. It is impossible to write history, or to describe contemporary fact, without passing judgments of value on particular situations—judgments that are often passed simply by the use of adjectives. To be valid, or even understandable, these judgments must, of course, be based on a sane appreciation of the relativities of history and on a just allowance for the inevitable gap that always separates theory from practice; but it is even more important that they should rest on principles that have been antecedently formulated and supported by orderly argument.

An historical discussion of the problem has already been begun in these pages, by a consideration of it in its early origins;1 its further historical development, will, I hope, be explored. In this article, I am undertaking to begin a statement of Catholic principles in the matter, with a view to showing how they organize themselves into a complete theory.

THE PROBLEM OF A FRAMEWORK

The initial task is that of setting up a framework of discussion that will reveal the structural lines of our rather complex position. It is,

[p. 230]

of course, sometimes said that our position is summed up in the two formulas, “dogmatic intolerance” and “personal tolerance.” For my own part, I feel that neither of these formulas is happy, as a formula; in fact, I should like to see both of them disappear from circulation as rapidly as possible. They are, of course, entirely open to legitimate criticism and even rejection, since neither of them has any status in official sources—from Mirari Vos onwards, or backwards—and neither of them is part of our technical theological vocabulary.

First of all, my fear is that the sheer use of the antithesis, “intolerance” versus “tolerance” may foster a common falsification of the whole problem in the popular mind, as if the crucial issue really were “intolerance” versus “tolerance,” in the popular meaning of those terms. Again, I fear lest we seem to present a false choice to the popular will, which is not guided by nice thinking but by slogans. As a matter of fact, Catholic attitudes are widely, and wrongly, characterized as “intolerant,” and Protestant (and secularist) attitudes are customarily regarded as “tolerant.” Confronted, therefore, with the issue in terms of “intolerance” versus “tolerance,” the popular mind will not hesitate. It is under the influence of the contemporary mood, and all the emotions that guide its thinking will inevitably determine its choice of “tolerance,” with all its implications.

This matter of words is extremely important. The Church has at times been forced to abandon even some of her own splendid words because of the misleading connotations that grew up around them; think, for instance, of the grand formula, “Christian democracy,” which fell on evil days; only recently—now that half a century separates us from the unfortunate French debates—could it be revived, as, indeed, it should. We are not in a position to control the connotations of words and their emotional impact. And in dealing with the issue of religious liberty—an issue already sufficiently explosive, and loaded with an emotion whose tide sets against our case—it should be a principle with us to avoid, as far as possible, the use of words that are emotionally explosive. Let me say here that the issue is not between courage and timidity in setting forth our integral position, but simply between apt and inept ways of doing it. I believe, of course, in the Kerryman’s principle of “striking a blow at times for the faith”; but I should personally prefer to avoid the pugilistic error of leading with one’s chin.

[p. 231]

The formula, “dogmatic intolerance,” is particularly objectionable, because of its contemporary connotations. We are normally desirous of showing that our position with regard to religious liberty, although complex, is quite reasonable. It would seem, therefore, advisable not to state it in a formula that from the outset prejudices the case against its reasonableness. As a matter of sheer fact, the word “intolerance” is synonymous in the popular mind with all that is unreasonable, and positively hateful. In customary usage, it does not designate a considered and serene intellectual and emotional attitude, formed in the light of the full truth and impregnated with profound charity; on the contrary, it stands for the entirely detestable tone and temper of a mind that is narrow, one-sided, impatient of argument, obstinate, prejudiced, aggressive, arrogant, and persecuting. As synonyms, Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary gives “bigotry,” “illiberality”; and Roget’s Thesaurus, “bigotry,” “dogmatism.” These are not charges to which we plead guilty. Why, then, should we seem to prefer them against ourselves by asserting that our position is one of “dogmatic intolerance”? Incidentally, the addition of the adjective “dogmatic” effectually locks all the doors to understanding that were already slammed shut by the word “intolerance”; in customary usage, it means “opinionated; asserting a matter of opinion as if it were fact” (Webster).

A very laborious effort is made, of course, to purify the word “intolerance” of its invidious connotations. It is said, for instance, that “truth is intolerant,” or that “everybody is intolerant on certain subjects,” or that “we are not intolerant in the way in which it is really intolerant to be intolerant.” But the first defense rests on an inexact metaphor, which transfers to things what is a correct adjectival qualification only of persons (truth is not “intolerant”; it just is, most serenely—and, anyway, why saddle religious truth with an opprobrious epithet that is not customarily smeared onto the truth in any other field?). The second defense adds only heat, not light, to the debate, since it merely answers a charge by a counter-charge, that provokes denial. And the third defense is altogether too subtle for the popular mind, whose stubborn unthinkingness is not perturbed by nice distinctions between kinds of intolerance, once it has made up its mind to hate all “intolerance,” in obedience, if not to the dictates of Christian charity, at least to the denunciations of the

[p. 232]

newspapers. I am thinking predominantly of this popular mind when I suggest that the formula “dogmatic intolerance” should be quietly taken out and buried. It was not originally a Catholic coinage; it was foisted on us. I do not see why we should seem to accept it, or laboriously strive to sweeten it with distinctions. The thing to do is flatly to reject it. We can at least exile it from our own vocabulary, as a positive hindrance to a right understanding of our position.

The formula, “personal tolerance,” is hardly more acceptable, as a formula. It seems to be a particularly horrid way of describing the Christian virtues of justice and charity, which are the sole norms that govern relations between persons as persons. Perhaps there is no need to say more about it. It just doesn’t say what it is supposed to say; and that is rather a good test for a bad formula. I should like to see it share the same grave with its equally unrevealing counterpart, “dogmatic intolerance.”

In this whole matter of religious liberty, the fatal thing would be to fall into the fallacy of simplism that we so easily detect in the theories of our adversaries, and especially in their formulas. I do not think there is a brace of formulas that will state, without deforming, the Catholic position. About all one can do, by way of initial simplification, is to state the fundamental tension in our position somewhat after this fashion: We love God in the truth that He has given us, and we love man in that which is most divine in him, his conscience. We love God and His truth with a loyalty that forbids compromise of the truth, even at the promptings of what might seem to be a love of man; were it otherwise, our love both of God and man would be a caritas ficta. And we love man and his conscience with a loyalty that forbids injury to conscience, even at the promptings of what might seem to be a love of truth; were it otherwise, our love both of God and man would again be a caritas ficta. In either case, what we abhor is any feigning. Perhaps St. Francis de Sales came as close as anybody to a good double formula, when he spoke of la vérité charitable and la charité véritable.

However, the difficulty is that there is no good double formula. And the most serious vice of the one already discussed, “dogmatic intolerance and personal tolerance,” is that it completely obscures

[p. 233]

what it is vastly important not to obscure—the starting point of our whole position. At its worst, it suggests to the popular mind that we begin with arrogant assertion, and end with persecution, being withheld from the latter only by a lack of sufficient political power. Even in the minds of the more intelligent, the implications may very well be that we begin with an appeal to the authority of the Church, and end, if we can, by an appeal to the authority of the State to uphold the authority of the Church. The first view is utterly ridiculous, of course. But even the second view is quite distorted; and it risks getting the whole discussion off to a false start.

Actually, to one who has seriously studied the great modern conflict on religious liberty, that raged over the famous “principles of ’89,” it is quite clear that the Church took her initial stand, not on the grounds of ecclesiastical authority, but on the grounds of human reason. She collided with the doctrinaire assertions of the so-called Liberals with regard to the conscience of man and its “freedoms” and with regard to the State and its “rights”; and to these assertions she, initially, and devastatingly, opposed a doctrine of the conscience of man and its duties and of the State and its limitations. Obviously, the theological issues in the whole conflict were real and essential; it was of the Church that the Liberals said: “Voilà l’ennemi!” However, the initial and fundamental issue was not a point of revealed dogma—the constitution of the Church and her authority; basically at issue were a series of points in moral and political philosophy—what is liberty, what is conscience, what is the State, what are the “freedoms” of conscience and of the State.

This fact, of course, was not so clearly marked in the earlier days of Pius IX. He was not a great philosopher. If he had been, or if he had been surrounded by great philosophers, or, in a word, if the neo-Scholastic revival had taken place a century earlier, the whole polemic of the Church during the revolutionary era might well have had a different character, and perhaps even a different outcome. We know, of course, by faith that what the Church defends is always right and true; but it would be simple credulity, not faith, to suppose that the actual details of her strategy and tactics in defense of the truth are always divinely inspired. At all events, the fact that the dispute over the “modern liberties” was basically a philosophical

[p. 234]

dispute emerges with some clarity even from the Syllabus; it is entirely evident by the time of the Vatican Council; and it is perfectly luminous in the work of Leo XIII, as anyone who has studied Immortale Dei and Libertas can testify.

THE THREE LEVELS OF THE PROBLEM

I think it important, therefore, to be explicit and insistent on the fact that the Church’s theory of religious liberty rests initially and fundamentally, not on the dogmatic assertion of a theology of her authority, but on a philosophical explanation of the structure of the human conscience and of the State, for whose validity reason itself stands sufficient guarantee. Obviously, the whole problem cannot be solved simply in terms of philosophy. In the present order of the Incarnation, philosophy is not the supreme wisdom, nor is reason man’s most decisive guiding light. Faith is the fuller light, and the principles of theology complete, without destroying, those of philosophy. Consequently, the problem of religious liberty must move on from its initial philosophical position and be given a theological formulation. However, when this happens, the philosophy of conscience and of the State is gathered up and carried along to the new ground; and it is made pivotal even in the theological solution of the problem. Finally, since freedom of religion is a problem that intimately concerns the social life of man, as that life is lived in a particular set of conditions, the problem must receive its final formulation in terms of the varied and contingent realities of an individual social context. Here, too, a philosophy of conscience and of the State is still integral to its solution.

This is the architecture of the problem itself, and consequently of the Church’s solution to it. But this pattern is in nowise suggested by the very unrevealing formulas, “dogmatic intolerance” and “personal tolerance”; on the contrary, they obscure the pattern and completely fail to reveal the inner logic of its solution. Discarding these unhelpful tags, therefore, I am going to suggest that the Catholic solution to the problem of religious liberty must be set forth on three distinct planes, the ethical, the theological, and the political. Actually, involved in the issue are three problems, distinct indeed, but, in the present order of salvation, not separable. They are of progres-

[p. 235]

sively increasing complexity; and they must be handled in their natural order, if we wish to keep all the issues dear and build up the complete solution into a harmonious whole, revealing its organic structure, the lines of its logic, and the completeness with which it satisfies all the pertinent values.

The first problem is abstract and ethical, and its principle of solution is solely the light of reason. Properly speaking, it is problem of the freedom of conscience. The factors in it are God, the moral law, the human conscience, and the State (meaning civil authority in its function of effectively directing citizens to the common good of the organized community).

The second problem is again abstract, but theological. Its principle of solution is the light of revelation, as completing the light of reason. Properly speaking, it is the problem of Church and State. The factors in it are God and the moral law, Christ and the law of the Gospel, the Church, the Catholic conscience, and the State (in the same sense as above).

The third problem is concrete and political. Its principles of solution are the light of revelation, as completing the light of reason, and the precepts of political prudence with regard to the achievement of the common good of the political community. Properly speaking, it is the problem of constitutional provisions for the rights of conscience, both in the international community as such, and in particular national religio-social contexts. Its factors are God and the moral law, Christ and the law of the Gospel, the Church and the Catholic conscience, the churches and the synagogue and the consciences of their adherents (perhaps also the secularists and their “conscience,” if they have any), and the State (again in the sense described).

The increasing complexity of the problem, as it ascends through the three orders of discussion, is quite plain. And it is plain, too, from the bare enumeration of the factors involved, that we are confronted with a problem of organization. All these factors enter into reciprocal relationships; our problem is to construct the right dynamic system of relationships—to make an order out of a collection of elements. When we have done this and have formulated the results in terms of law (natural law, canon law, civil law), we shall have solved the problem of freedom of religion. That is, we shall have solved it in principle;

[p. 236]

it will still remain to make the solution work, through the cultivation of the right personal attitudes of justice and charity and through smoothly functioning social institutions. Actually, the final, concrete solution is in terms of virtue, not simply in terms of a sheer definition of relationships. But the relationships do have to be determined; and we shall determine them by a study of the nature of each element involved—what is God, what is conscience, what is the Church, what is the State, etc.

THE PERSPECTIVE OF THE CATHOLIC SOLUTION

Here, perhaps, is the place to insist that, even in the midst of its enormous complexity, the problem of religious liberty never wavers from its focus on one single, simple, and basic issue. I mean the freedom of the human person to reach God, and eternal beatitude in God, along the way in which God wills to be reached. I put this statement in such a way as positively to exclude any suggestion that it is ultimately the will of man, and not the will of God, which determines the way along which man is to reach God. Moreover, in making the statement I am not giving the slightest encouragement to any individualistic concept of religion, that would view the individual somehow saved in isolation, or in some purely “spiritual” way. I wish simply to express the profound truth and the imperative will of God that emerge from St. Paul’s awed utterance: “[He] loved me, and gave himself for me” (Gal. 2:20). Each human being is unique, in himself and in the unique situation he occupies within the concrete unity of mankind; each is the object of an unrepeated divine creative will; each in his uniqueness is the object of Christ’s redemptive act; each is destined for an eternal union with God and with His saints, that will be singular in its degree, and that will be reached under the direction and protection of a particular providence, operating within the structure of God’s universal salvific will. And what God ultimately wills is that the unique love which He has for each of His redeemed creatures may have its consummation in the ordered sanctity of heaven. Ultimately, God wills to save men.

It is, of course, no less obligatorily God’s will, manifested by Christ and displayed to the world by the Church, that man’s sanctity is to be begun on earth, and sought in the one Temple of the Holy Spirit,

[p. 237]

the one House of God, the one Body of Christ, the one Fold of the one Shepherd—in a corporate society that is visible and hierarchic, wherein a living voice teaches, and human pastors rule, and sanctification is sacramental. But this is an “economy,” a dispensation, divinely willed and wisely willed, because it is suited to the conditions of human life, and to man’s temporal bondage to the necessities of matter. As God, through Christ, has instituted this economy and made it obligatory, so He will save it, and all that is visible and institutional in it, until the end of time. But He does not will to save it eternally; for it is of time and for time, and it will end with time. The days of the visible, hierarchical Church are literally numbered; they will run out when there are no more “days,” but only an eternal Now. The magisterial authority of the Church, her hierarchy of jurisdiction, and her sacramental system are divine in their origin and institution, but temporal in their finality. In heaven the only magisterial authority will be the divine mind itself, to which the soul will have direct access; the only hierarchy will be that of sanctity; and the only sacrament will be the glorified Humanity of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. The Church, as a juridical society, exists iure divino, indeed; however, it does not exist to save itself, as it were, but men.

All this, of course, implies no false separation between the Rechtskirche and the Liebeskirche in the present economy; the Body of Christ is one; it is at once the mystical fellowship of the Spirit and a juridical society; and its two “lives” are as much one as the life of body and soul. However, all this does set our perspectives. In the present matter, it establishes the fact that here on earth the thing of supreme and ultimate importance is that the human person should be free to reach the place to which God has predestined him in heaven’s eternal hierarchy of sanctity. The Church has never thought otherwise. It is not, for instance, a ceremonial gesture that the Roman Pontiff, symbol of the Church’s institutional reality, signs himself, “Servus servorum Dei.” The whole of the so-called “institutional action” of the Church, whether in her mission to souls or in her mission in the temporal order, has no other ultimate focus than the protection, support, and perfecting of the freedom of man to reach his eternal destiny. As I shall later show, even when the problem of freedom of religion appears on the theological plane as the problem of Church and

[p. 238]

State, the basic issue involved in it is the freedom of the human person, Christian and citizen, to live at peace in Christ and in society, that he may thus move straight on to God. This was clearly the thought of Leo XIII, who was in the center of the stream of Catholic thought. Like his predecessors and successors in the see of Peter, he championed the “rights of the Church,” and contended for right juridical relation-ships between the Church and the secular power. But this combat has always been, as it were, of the surface. It has been important, and often very fierce, only because the stake in it was on a level far deeper than the level on which the combat itself was fought. Actually, the stake was the ultimate human value, the freedom of the soul of man to go to the Father, through Christ, in the Spirit and in the Church; and in secular society—the freedom to live that true life, personal and social, religious and civic, which is the inchoatio vitae aeternae.

These perspectives—the perspectives of eternity—are maintained with ease by the Catholic; for he sees the Church from within, and grasps her profound aims underneath all the conflicts and manoeuvres of the surface. I dare say that he is at times puzzled by some of the manoeuvres, and at times, too, he doubts their tactical value; hence the multitudinous controversies among Catholics, usually about matters of what is called diocesan policy, or even about movements of Vatican diplomacy. At all events, no matter how the Catholic may judge the tactical value of this or that “institutional action” of the Church, universal or local, past or present, he is by no means inclined to mistake its final purpose, nor to suppose that it pursues any other goal than what Catholic phraseology calls “the good of souls,” all souls, be they Catholic or not—the eternal interests of the human person and the progress of mankind through an ordered temporal life towards its supratemporal destiny, opened to it by Christ. Beyond these interests, which are identical with the purpose of the redemption, the Church has no other “institutional interests.”

On the other hand, it is extremely difficult for the average Protestant so to situate himself as to be able to view the existence, the nature, and especially the “institutional action” of the Church in the perspectives of her primal and single concern for the basic human liberty to reach God as God wills to be reached. The reasons for the difficulty are numerous; and to explore them would lead us to measure the width

[p. 239]

and the depth of the magnum chaos that centuries of doctrinal division, religious development, and secular evolution have established between Catholics and their separated brethren. This cannot be done here. But possibly it would be worthwhile to undertake the positive task of stating Catholic doctrine on religious liberty in such a way as perhaps to reveal the perspectives in which it is conceived, as well as its own internal structural lines. The present article will deal only with the first facet of the doctrine—the foundations of our whole position, which are laid in the solution of what I have called the ethical problem.

THE QUESTION OF A COMMON STAND

Let me here put in a preliminary note. I have said that the architecture of the Catholic solution of the problem of religious liberty follows the architecture of the problem itself. I would go on to emphasize the fact that no one is at liberty to alter the architecture of the problem to suit himself. Essentially, the problem involves an ethic of conscience, a theology of the Church, and a political philosophy of the State. And it is absolutely impossible to conceive any solution to it, except in these terms. Protestant solutions, if they pretend to be vertebrate, and intellectually respectable, must necessarily repose on certain positive tenets in ethics, theology, and political philosophy. They cannot be respected if they rest simply on empirical or emotional bases, much less if they float in the air, supported only by the lighter-than-air content of an assemblage of catch-words, and least of all if their major premise is simply the negative one of opposition to “the Roman Catholic hierarchy.”

Fortunately, the more seriously thought-out Protestant solutions do invoke an ethic of conscience, a theology of the Church, and a political philosophy. Sometimes these elements are not sharply defined, nor strongly integrated; but they are present in some form. For this reason, I feel that there may be some hope of communication across the boundaries that divide Protestant and Catholic. There is even some possibility of agreement, in the midst of serious disagreement. Briefly, I would put, the possibilities thus: (1) we can reach an important measure of agreement on the ethical plane; (2) we must agree to disagree on the theological plane; (3) but we can reach harmony of action and mutual confidence on the political plane, in virtue of the agreement previously established on the ethical plane as well as in

[p. 240]

virtue of a shared concern for the common good of the political community, international and national.

It is this third objective that is presently desirable—in fact, strictly necessary; for both Catholics and Protestants have a common obligation to preserve harmony of action and mutual confidence on the political plane, in the interests of their common good—public peace, civic friendship, the reign of justice in social life, temporal prosperity. Competent observers have noted that the issue of religious liberty is contributing powerfully to the heightening of tension between the Catholic and Protestant groups. The difficulty in the way of social concord is obvious. Catholic and Protestant theologies of the Church are radically divergent and irreconcilable. Moreover, Protestant say that the Catholic doctrine of the Church has implications with regard to the temporal order that are unacceptable (that is the mildest word they use). On their side, Catholics say that the Protestant doctrine of the Church has implications in the temporal order that are likewise unacceptable (again, the mildest word). Here, therefore, is our problem—a common problem: While preserving intact our theological disagreement (which has its own grounds), how shall we abolish mutual distrust, and strengthen our social unity, civic amity, harmony of action and mutual confidence in a common pursuit of the common good? Obviously, the dilemma is not to be solved by abolishing one of its horns, the theological disagreement. In reason, we cannot be asked to accept a solution to the problem of religious liberty that is conceived in terms of Protestant ecclesiology. In turn, we cannot demand that the solution of the problem be postponed until Protestants shall have accepted our ecclesiology.

So far as I can see, the only solution to our common problem must be along the following lines. Our subsistent theological disagreements will cease to generate suspicion and separatism on the level of social life, when both sides have the assurance that their opposing theologies of the Church are projected against the background of ethic of conscience and a philosophy of political life that are based on reason, that are therefore mutually acceptable, and that are not destroyed by the disagreements in ecclesiology. This ethic of conscience and this political philosophy will stand guarantee that respective theologies can under no circumstances have such implica-

[p. 241]

tions in the temporal order as would be injurious to the integrity of conscience, be it Catholic or Protestant.

It is with a view, not only to following the pattern of the problem itself, but also to working towards this practical concord between Catholics and Protestants that I should insist on beginning discussion of the problem of religious liberty on the ethical plane. There is also a further reason. It would be unfortunate to see this problem become simply a Catholic vs. Protestant issue. The problem is really much wider, in the form that it assumes in various national scenes, including the American, and in the form that it has on the international level. And there is reason to fear that, while Catholics and Protestants are having a merry dispute, the secularists and totalitarians will move in and solve the problem in their own way—the secularists, by evacuating the concept of religious liberty of all ethical content; and the totalitarians, by forcibly destroying the concept itself, whatever its content. The differences between Catholics and Protestants are very real and important; no less real and important is the necessity of seeing that two common enemies of each do not triumph over both. There is a stand to be made against secularism, which makes freedom of religion mean freedom from religion, and which is particularly dangerous in its denial of the relevance of religion to social order and public life. And there is a stand to be made against totalitarianism, which destroys freedom of religion by destroying religion itself through the imposition of the cult of the absolute State. The stand against these two enemies can be made on the ground of human reason and the natural law, that define the nature of the human conscience the nature of the State. On this ground, therefore, Catholics and Protestants can make a common stand, as an act of good will—a will that has for its object a common good.

THE ETHICAL PROBLEM

On the ethical plane, the problem of religious liberty is abstract in a twofold sense. First, we choose to discuss it solely in the light of the nature of the elements involved in it; we move in the order of essences as such. It is not a question of religious liberty in Spain, or the United States, or at any particular period of history, but of religious liberty in itself, as an endowment of man as man. Secondly we choose to consider the problem as purely philosophical, and we

[p. 242]

aim at a solution solely in terms of human reason. We admit into the problem only those elements whose existence is certified by reason and we construct our solution out of only those conclusions which reason validates. In a word, we are supposing that the problem is posited in what Catholic thought calls “the order of pure nature”; we are moving in the universe of discourse characteristic of Scholastic ethics, the natural science of morals, whose single architect is human reason.

Consequently, we prescind from all the realities of the present, historic, supernatural order, which are certified to us only by revelation and known only by faith. In particular, we prescind from the fact of Christ, on which the whole supernatural order of salvation built. We leave out of consideration His teaching and His mission and His Church—her authority, ministry, sacraments, Scriptures, law. In the purely natural order in which we are moving, there is still one true religion; but its creed is simply that sum of truth about God and man which reason can discover from the works of God; it includes the existence of God as a personal being, the author of all things that are, infinite in perfection, provident over the world and especially over the life of man, of whom He is the last end and highest good, etc. And the moral code of this natural religion embraces simply the precepts the natural law with regard to man’s essential duties towards God, himself, and his neighbor. And this moral law is mediated to man conscience.

In this order, too, we can conceive the existence of religious associations; but they would be purely voluntary in character; they would owe their existence and their constitution and the determination of their purposes solely to the will of man, and they could be altered or joined or abandoned simply at man’s own choice. There would be only two natural, and therefore obligatory, societies—domestic society and civil society; to them man would be impelled by needs inherent in his nature as such, and they would be the only two necessary social means and milieu in which he would be obliged by nature to seek, rational and human perfection. Consequently, there would be only two moral authorities empowered to impose obligations on conscience, there would be, first, parental authority in the home, and secondly civil authority in the political community. This latter would be superior to the individual conscience, but only in its own order—the

[p. 243]

order of social life and the common good; in this order it would effectively oblige the individual in conscience to obey just laws and to give his necessary co-operation toward the common good. At the same time, civil authority and the organized community of which it is the directive principle would itself be subject to the sovereignty of God and bound to obey the moral law in all its actions.

This is a very rapid sketch of the religious and moral universe, as it would be known simply to reason, apart from revelation. In a sense, it is an unreal universe; but only in the sense that it is not a complete picture of the universe as it is in our present, historic order. As far as it goes, it is a valid picture; and any conclusions about man’s religious freedom that we draw while operating in this universe will be entirely valid, not to be destroyed, but only completed by the further conclusions that revelation will impel us to draw. They will be conclusions based on the very nature of man; and man’s nature has not been destroyed but perfected by its elevation into a supernatural economy.

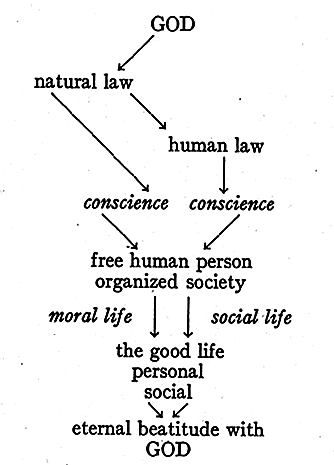

Positing our problem, then, in this abstract universe of discourse, we find it composed of the following elements, which may be disposed in a diagram that will to some extent indicate the structure of the problem itself:

[p. 244]

The focus of the problem is on the human person, who is a member of organized society. And the problem itself is that of determining the immunities and the positive empowerments which the human person enjoys, inasmuch as it is a human person, the image of God (a rational and free moral agent), destined both to “the good life” on earth and to a supratemporal beatitude, under the direction of the authority and law of God, and under the direction of civil law and authority—both of which laws are mediated to the person by conscience.

Liberty and Law

First of all, it will be noted from the very statement of the problem that it supposes a very intimate relationship between liberty and law. This supposition needs to be examined briefly.

We are, of course, dealing with liberty in the moral sense, not in the purely physical sense. In the latter sense, liberty—natural liberty, as it is called—is the property of the human will whereby man is master of his own acts, immune from the mechanical or psychological determinisms that are the single spring of action in the vegetative and animal kingdoms. The free will is the potentia ad utrumlibet, a faculty of choice between alternatives—acting or not acting, acting thus or so. Natural liberty is not the same as moral liberty, but it is the presupposition and condition of moral liberty: man is a moral agent, responsible for his own actions, because he is master of them. Moreover, in one cardinal respect, natural liberty illustrates the nature of moral liberty: as, in the physical order, man’s natural freedom, is intrinsically related to his power of reason, so, in the moral order, man’s moral freedom is intrinsically related to the ordinances of reason, which are law—ordinatio rationis. Moral freedom and moral law are as essentially correlated as the natural faculty of free choice and the natural faculty of reason.

The point needs great emphasis, as against current antinomian theories, consciously or unconsciously held, which tend to conceive liberty as sheer release, total emancipation, an indefinitely expanding spontaneity—in a word, an Absolute, over against which the authority of law can stand only as an enemy, a destructive force, to be submitted to only as one submits to a police power. This is sheer absurdity.

[p. 245]

Hardly more acceptable is the view that considers law as coming to liberty from the outside, as it were; as if law were simply a principle of repression, whose imposition on man could create at best only an uneasy and unworthy state of heteronomy. Actually, the case is quite otherwise. The notion of law is to be discovered at the very interior of the notion of liberty, in such wise that liberty itself is unintelligible apart from law as its root, support, light, guide, and ally. Without going into the subject at length, the fact itself may be substantiated.

In the physical order, the will of man is self-determining, actively indifferent towards acting or not acting and towards acting thus or so, because there exists in man the faculty of reason. By virtue of his reason, man is capable of surveying the whole range of truth and goodness, of deliberating about the values that it contains, and of judging that here and now this value is desirable, and to be pursued. Apart from this previous deliberation and judgment, there is no free act. And every free act is an obedience to a judgment of reason.2 Precisely in the privilege of being obedient only to reason consists the freedom of the will—its immunity from all less noble determinants. So far, then, from freedom being simply an escape from obedience, the notion of obedience is inherent in the very notion of spiritual freedom: “by its nature [the will] is an appetite obedient to reason.”3 The principle that man’s freedom is inherently an obedience to reason is true even on the plane of the psychological process; but it prevails with still greater vigor on the plane of man’s moral freedom. Here, too, the fundamental point is the intimate” relation between freedom and reason. But now reason appears, not simply as the power to weigh particular goods and judge them desirable and present them to the will for acceptance as such, but also as the power to discover and understand the “order of reason,” as an order—I mean the relation of man to God, his author and last end, and the relation that all free human action has to the attainment or loss of this last end. Reason

[p. 246]

discovers the dignity of man as the image of God, created by Him as His image, coequal with the other members of the human family, whose proper perfection consists in making his rational, free, and social nature perfectly rational, free, and social. With his dignity, man discovers his destiny, which is God, and the possession of God, man’s highest good, the only Absolute Good, to be willed of necessity, for its own sake, above all things and in all things. And in the fact of his destiny to the possession of God, man discovers the dominating principle of the order of reason, and the norm whereby to make true judgments of value. Formed in the light of an understanding of this order of reason, man’s individual judgments acquire a new force. They not only state what is good and what is evil; they also dictate that the evil is to be avoided and the good done. The judgment of reason appears as an imperative of reason, prescribing to the will what it must reach for, and what it must turn away from, in order that man may reach his proper perfection and his last end. This formulation of the demands of the order of reason is what we mean by law—ordinatio rationis.

Confronted with this moral imperative, the function of freedom again appears as an obedience, an acceptance of the order of reason and its concrete demands. This acceptance is the act of moral freedom. By definition, then, moral freedom consists in man’s deliberate obedience to moral law. Consequently, in yielding this obedience, the free human spirit does not submit to an alien force, to an unworthy heteronomy, that would violate or diminish its own freedom; for it is in the very nature of freedom to be obedient to reason, and to submit to the imperatives, the laws, that derive from the order of reason. When it obeys and submits, it perfects its own freedom. So far from being hostile to liberty, or even antithetic to it, law is the intrinsic complement of liberty. The moral life of man is essentially bipolar; it is vitalized, made human, made free and ordered by the salutary tension between the two poles, liberty and law. It was in this sense that Leo XIII wrote:

The radical reason for man’s need of law is to be found in his own faculty of free choice—that is, in the need for harmony between the will and right reason. It is a complete perversion and inversion of the truth to imagine that, because man is by nature free, therefore he should be free from law. If this

[p. 247]

were the case, it would follow that liberty, in order to be liberty, would have to be loosed from all vital relation with reason. As a matter of fact, the very opposite is true: because man is free, therefore he must be subject to law.4

This has been a very sketchy treatment of a difficult, if fundamentally simple, question; but perhaps it will serve our present purpose. One thing, however, needs to be added. We know that human reason is not infallible; the possibility of erroneous judgment is native to it, not indeed as a perfection of reason, but as its essential imperfection. As a created reason, it is of its nature defectible; as a human reason, it is dependent on matter and sense; it is obliged to proceed in concepts, which are partial views, and difficult to combine; and it is subject at every step to the influence of sentiment and passion. Consequently, in its function of being a light to the will, reason can at times play the role of an ignis fatuus, and in obedience to its leading the will can go astray after a good that is delusory. Even when this happens, the will continues to be, in a sense, obedient to reason; for it can pursue evil only under the guise of good, and this guise is thrown about evil by the mind’s “rationalization,” which presents a specious value to the will as if it were real. Even when man sins, he sins in obedience to reason—reason misled and misleading. Moreover, this obedience to falsity is free. But what man achieves by his free sin is not freedom; actually, he enters into a state of slavery. Retentus terminis alienis. He gives himself over to error and evil—constraints that are foreign to the very nature of the human mind and will, bonds that are unworthy of the free human spirit. For this reason, our Lord said: “He who acts sinfully is the slave of sin” (John 8:34). And on this theme St. Augustine wove some of his most profound analyses of the nature of freedom, as well as of the nature of grace. For our purposes, it is important to keep in view the essential difference between the two “freedoms.” There is man’s “freedom” to err and sin, which is very real, and terrible, but only speciously a freedom; for it cloaks what is, in fact, a slavery. And there is man’s freedom to live and act under the domain of law, and to conform his life and action to the order of reason—cui servire regnare est.

It has been necessary to say this much about the relation between liberty and law; otherwise we could not appreciate our problem. If

[p. 248]

the problem of religious liberty were posited in terms of the so-called liberal concept of freedom, it would be ineffably easy to solve. Or rather, there would be no problem at all—no ethical problem; for the ethical problem begins only when one perceives the necessary relation between moral liberty and moral law.

By reason of this necessary relation, the problem of religious liberty also appears as a problem of the juridical order—the order of relationships that are established in terms of reciprocal rights and obligations. The term “liberty” designates initially, of course, an exemption, an immunity from coaction, prohibition, restraint, or compulsion; but it likewise implies a positive empowerment to do or demand something. When an immunity and a positive empowerment are viewed as having their origin in law (either the law of nature or human law), the “liberty” they assert appears, as a right; and, as a right, it connotes an obligation on the part of others not to violate the immunity or impede the exercise of the empowerment. It was for this reason that I defined the problem of religious liberty as that of determining “the immunities and the positive empowerments” of the human person, under a system of law.

THE TWO LAWS

The primal law to which human liberty is related, as to the basic principle of its true liberation, is the natural law. We cannot here undertake to explore this concept, which has of late emerged to a new prominence. It will be sufficient to give a definition of it, in the words of Leo XIII:

The first and foremost [guide of human action, whereby man achieves his full freedom—so the context] is the natural law, which is written and engraved in heart of each and every man; for it is human reason itself, commanding us to do what is right and forbidding us to sin. A precept of reason, to be sure, cannot have the force of law, except insofar as it is the voice and interpreter of a higher reason, to which our mind and liberty must be subject. For the force of law is to impose duties and to grant rights; and consequently, law depends for its force wholly on authority—that is, on a true power of prescribing duties and defining rights, and likewise of sanctioning commands with rewards and punishments. But it is clearly not within the power of man to exercise this authority over himself; he is not, therefore, the supreme legislator in his own case, nor does he set the norm of his own actions. The further consequence is that the law of nature is the

[p. 249]

eternal law itself, implanted in those who are endowed with reason, and causing them to move toward the action and the end to which they are destined. And this eternal law is the eternal reason of God, creator and ruler of the world.5

For our present purposes, the thing to remember about natural law is the simple fact that it is truly law—not, of course, “written” law (a statute or a code), but “unwritten” law. (The traditional metaphor, “the law written in the heart of man,” may be misleading; it indicates the origin of the law from nature, not its form.) Natural law is the ensemble of things to be done and things not to be done which follow of necessity, from the sheer fact that man is man. The necessity of doing or avoiding these things is perceived, not created, by reason, which then issues the ordinances of reason which are, in effect, natural law. Reason, indeed, issues the ordinances; but it does not of itself make them ordinances, binding rules. They are such because they reflect the eternal mind and purposes of God, which decree that man should be man, and should act as a man, and move toward the destiny of man. The ordinances of reason are law, but they have the force of law only because they are “the voice and interpreter of a higher reason.”

The second genus of law to which human liberty is related, again as to a principle of liberation, is human law. Its root is in the social nature of man; and it expresses the demands of reason with regard to social life—above all, the primary demand that human society should be a co-operating unity, wherein free men associate themselves, under authoritative guidance, in pursuit of a common good. It is possible here to give only a bare outline of a philosophy of human law; and this may be done in another text of Leo XIII:

What reason and the natural law do for men in their individuality, human law, enacted for the common good, does for them in their association [it assures the harmony between free action and reason—so the context]. There is one type of human law which deals with what is by nature good or evil, and which bids men pursue the good and avoid the evil, adding a proper sanction. Precepts of this kind, of course, do not have their first beginnings with society; for, as society did not itself produce human nature, so it does not originally make some things suitable to human nature (and good), and other things unsuitable to human nature (and evil). On the contrary, precepts of this kind antecede all social living; their source is to be found in the natural law, and consequently in the eternal law. For this

[p. 250]

reason, when the precepts of natural law are enacted in the laws of men, they have more than the force of merely human law; they chiefly represent the much higher and more majestic imperatives that proceed from the law of nature and the eternal law. And with respect to this kind of law, the precise function of the legislator is to establish a common system of discipline, that will make the citizens obedient to these laws [natural and eternal], by restraining those who are wayward and inclined to violations of morality. His purpose is to see that they are deterred from evil and pursue what is good, or at least that they do not become a cause of vexation and injury to the community.

There is another class of prescriptions of civil authority, which do not immediately and proximately flow from the natural law, but only remotely and indirectly, inasmuch as they define the details of certain courses of action for which nature has made provision only in a broad and general way. For instance, nature commands citizens to contribute their share to the public peace and prosperity; but the measure of the contribution, the manner of making it, and the areas in which it is to be made are not determined by nature but by the wisdom of men. As a matter of fact, human law, properly so called, consists precisely in these rules of life, which are devised by reason and prudence and declared by legitimate authority. It is human law which prescribes to all citizens how they are to co-operate toward the end set before the community, and which forbids them to go off in other directions. And inasmuch as it is dependent on the prescriptions of nature and in harmony with them, human law is a guide to virtue and a deterrent from evil. From all this we may gather that the norm and rule of the liberty of the social community, as well as of the individual, is the eternal law of God.6

It is evident that the philosophy of human law here outlined has as its counterpart a philosophy of the State as the agency for the enactment and enforcement of law. This latter philosophy asserts the moral nature and the moral function of the State. It asserts, first, that the State, in its legislative function as in all its functions, is not an amoral entity, that escapes the control of a higher law—the law of nature and of nature’s God, which exists before and above all human society. In other words, it asserts the principle embodied, in the first point of the famous Pattern for Peace, that “not only individuals but nations, states, and international society are subject to the sovereignty of God and to the moral law which comes from God.”

Secondly, this philosophy asserts that the State has a moral function, as well as purely material, administrative, and police functions. Itself subject to the moral law, it is the legitimate instrument for in-

[p. 251]

suring the observance of the moral law, and for determining the exigencies of the moral law, in the domain of community life. In its actions and policies, and especially in its legislative code, it cannot maintain a position of “neutrality” or indifference, disposed to accord equal rights to good and evil, and to view both with equal complacency. Of its own nature, the State, through its laws, is a power singly for the common good, which is not only material but moral in its scope, and includes civic virtue as its primary component. It has, therefore, the function of seeing to it that good is done and evil avoided. The sphere of its competence in moral matters is, of course, strictly limited, extending only to such matters as have a bearing on the common good; but within this sphere it has a true moral authority and can oblige in conscience. And as a moral authority, its ultimate purpose is to assist in preserving and perfecting the liberty of the community—its true liberty which consists in the harmony between social life and the order of reason. In this sense, Leo XIII, in the text already cited, concludes from the right philosophy of human law to the true nature of civil liberty:

In social life, therefore, the true essence of liberty does not consist in the fact that every man may do as he pleases; such “liberty” would tend to complete turmoil and confusion, and to the overthrow of the organized community. Rather, true liberty consists in this, that the regime of civil law gives every man fuller freedom to live according to the precepts of the eternal law. Similarly, the freedom of those in authority does not consist in their being able to issue commands at their own casual whim; such “liberty” would be equally criminal, and tend no less to the ruin of the State. Rather, human laws must get their force from the fact that they are understood to flow from the eternal law, and to sanction nothing that is not contained in it, as in the principle of all law.7

It is evident that this whole philosophy of human law and authority in their relation to human freedom stands midway between two extreme positions that have occupied political ground in modern times. First, there is the individualistic theory. On the one hand, it regards the individual’s freedom of choice—his initial, natural freedom, that extends to both good and evil—as the supreme freedom, absolutely sovereign, an end in itself; and correlatively, it regards the function of the State as simply the protection of the

[p. 252]

natural freedom of the individual. In fulfilling this function, it grants equal rights to good and evil as these are freely chosen; and its effort is simply to make all possible acts of free choice, good or bad, available to all men. Men thus appear as little gods, with no restriction on their freedom save this, that they are not to hinder a similar freedom on the part of others.8 The State has no moral function, but acts simply as an umpire between the conflicting freedoms of individuals. There is no moral law, relevant to social life and higher than the individual wills of the contracting parties who make up the State, of which the State is the executor. In its French costume, this theory was the fashion in the nineteenth century; but it is now discredited, since history has prove that this abstract theory of freedom for all men to do as they please has the concrete result of making freedom the privilege of a few, to the oppression of the many, and to the destruction of the common good.

At the opposite extreme stands the theory that has appeared in the world in German and Russian dress—the totalitarian theory of human law and human freedom. In it, the supreme freedom and the absolute sovereignty are assigned to the State itself, which thus displace the absolutely autonomous individual of the individualistic theory the great god, juridically omnipotent, an end in itself, a sort of Divina Maiestas, that claims the divine prerogative of being the source and fount of law. The function of the State is progressively to realize its own freedom, that is, progressively to aggrandize its own power. Correlatively, the function of the individual is to sacrifice himself to the achievement of the power of the State, which is the essential common task; and human law is simply the convenient means of insuring the fullness of this sacrifice. The citizen’s freedom of choice is abolished, as is also his freedom of spiritual autonomy—his right to the realization of his own moral freedom. There remains to him only unidirectional freedom of pursuing that which the State has decreed to be “good,” as conducive to the expansion of its own power. He

[p. 253]

becomes a slave, and he is supposed to be a happy slave, because he serves the supreme freedom of the State, cui servire regnare est.

Paradoxically enough, both of these extreme positions have a common root in the true principle that the function of law and authority is to perfect freedom. Their common error is a complete misunderstanding of the terms of the principle; for both of them fail to situate the idea of liberty and the idea of law in the framework of the eternal ratio Dei, which is the source of both liberty and law. Together, these theories deny the principle that “the norm and rule of the liberty of the social community, as well as of the individual, is the eternal law of God” (Leo XIII). Yet this is the principle that rescues society from becoming either an anarchy of atoms or a mechanized army of slaves. When both the freedom of the individual and the law of the State recognize a common subjection to the natural law as the reflection of the eternal mind and purpose of God, then human law is able to fulfil its true function of perfecting human liberty, and human liberty is able to fulfil its true function of perfecting human life, within the order of reason in society established by human law. The order of freedom and the order of law are harmonized: “the regime of civil law gives every man fuller freedom to live according to the precepts of the eternal law.”

CONSCIENCE

It was quite impossible to approach the ethical problem of religious liberty without having antecedently formulated a doctrine of the relations between liberty and law in general, and between liberty and he two laws to which it is subject. I have done this in barest outline. We have next to consider the notion of conscience, which appears so prominently in the diagrammatic statement of our problem as the median concept between liberty and law.

The word “conscience” is in that group of words which are posing the great contemporary problem of semantic. Its meaning, especially the much used phrase, “freedom of conscience,” is sometimes impossible to determine; and not seldom the term has no ethical meaning at all, being practically synonymous with individual good pleasure, that acknowledges no regulation by any ethical standard—so in the schools of subjectivist and secularist thought. Yet the tradi-

[p. 254]

tional ethics of the West has defined the concept very exactly, in itself and in its premises.

We have already touched on the premises—man’s freedom under the order of reason. On the one hand, the human person is really governed by law—a law that is “given” to it; on the other hand, the human person really governs itself—it gives the law to itself. The doctrine of conscience is the synthesis of these two principles, and resolves their seeming contradiction; in their light the function of conscience appears as essentially mediatorial. It is not the function of conscience to create the law of human life, any more than it creates God, or human nature, or human society. These realities are “given”; and with them the law of human life is also “given.” Standing, therefore, under a “given” law, the human person (conscience included) stands under a heteronomy. On the other hand, being endowed with reason and will, the human person is autonomous, master of its acts; and its autonomy must be respected even under the control of a heteronomous regime of law. To resolve this dilemma, it is necessary that law, remaining law, should become somehow interior to man; he must give it to himself, but as a law given to him.

He does this by conscience—a practical judgment of reason, whereby in the light of the known law a man judges of the morality of a concrete act, whether it is licit, or prescribed, or prohibited. In this act of judgment, the objective law is so mediated to man that it becomes his own law. Conscience, therefore, is the proximate subjective norm of human action—a norm that man imposes on himself; and the morality of an act depends immediately upon it. However, conscience is not the norm of its own rightness; it is itself regulated by a higher norm, not of its own creation—the eternal law of God, made know either in natural law or in the determinations of natural law laid down by legitimate authority. Conscience is not the judge of this higher law, but is judged by it. Conscience is not the legis-lator, but the legis-mediator; it is a standard of morality, but only as mediating a higher standard, and applying it to the concrete act. In his moral action, therefore, man preserves the autonomy proper to his condition, because in it he obeys a dictate of his own conscience. At the same time, he remains firmly under the heteronomy likewise proper to his condition, because the dictate of his own conscience ultimately de

[p. 255]

mands obedience, not because it is his own dictate, but because it applies the dictate of the eternal law. So conscience stands, as it were, between the objective law and the freely chosen act. Its function is essentially mediatorial—that of conforming itself to the order of the divine reason, in order that it may conform human action to this order. Not inappropriately, Newman compares conscience to a priest; for it truly distributes blessings and anathemas—not its own, but God’s.

As a matter of fact, the nature and function of conscience are rather admirably summed up in the traditional metaphor: “Conscience is the voice of God.” This statement immediately cuts between two extreme, and false, positions. First, it asserts that conscience is the voice of God; it is not God Himself. Hence it is not the final arbiter of truth and falsity, right and wrong. Man is indeed judged in the light of his conscience; but it is God who judges conscience. Only God is law in its source; conscience is but law in its application. On the other hand, conscience is the voice of God; it is not merely a human voice. Hence its commands come to us vested with a divine authority, that may not be disregarded under penalty of sin. Conscience is a sacred and sovereign monitor; for in its utterances we hear God Himself speaking.

We see, therefore, the dignity of conscience and its dependence; in fact, its dignity derives wholly from its dependence, as the dignity of the voice is that of the speaker. We see, too, that the first effect of conscience is a binding, and not (as is often supposed) a freeing. Initially, conscience is the principle of our enfeoffment to God and to His law; for in its commands God, as it were, takes the last step across the threshold of reason and seizes hold of us here and now. However, precisely because it enfeoffs us to God, conscience also enfranchises us from all that would hinder us on the way to God. The same voice that bids us obey also forbids others to interfere with the freedom of our obedience. In the more customary juridical terms, conscience has rights because it has duties; its freedoms are measured in terms of its bonds. What these freedoms are, we shall later determine. But it is already clear that among the rights of conscience is certainly not the right to debase the dignity of conscience by denying its dependence on God, ignoring the ultimate Lawgiver, and demanding respect for its very private fancy. A “conscience” that would assert such “rights”

[p. 256]

is a miserable counterfeit of the reality—a hollow, disembodied voice, in which there is no slightest echo of the majestic ring of the true “voice of God,” but only the childish, petulant accents of the voice of self-will.

The Rules of Conscience

The first, and the life-long, obligation of conscience is, of course, that of educating itself. This “voice of God” initially speaks with clarity only on the distinction between right and wrong, and on the duty of doing right and avoiding wrong. It must be taught all else; and the process of teaching and learning is extraordinarily difficult. Newman put the situation well:

But the sense of right and wrong, which is the first element of religion, is so delicate, so fitful, so easily puzzled, obscured, perverted, so subtle in its argumentative methods, so impressible by education, so biased by pride and passion, so unsteady in its course, that, in the struggle for existence amid the various exercises and triumphs of the human intellect, this sense is at once the highest of all teachers, yet the least luminous.9

How shall it be made luminous? This is a subject in itself, on which only three remarks can be made here. First, the education of conscience demands the cultivation of that measure of moral science which the individual requires to meet and make successfully the moral decisions that occur in his own context—family life, business life, etc. Obviously, the acquisition of this moral science demands consultation of the best moral thought of humanity throughout its history; it is more than ordinarily fatal for the individual to do his moral thinking in isolation. Again, the education of conscience demands cultivation of the virtue of prudence, whereby the conclusions of moral science are applied to particular cases, with a certain readiness of concrete judgment. But, above all, the educated conscience is acquired at the price of high moral discipline—the discipline of the moral virtues whereby reason is rescued from the dominion of pride or prejudice or passion, and from the subtle influence of self-deception or evil habit, and from the general “darkness” in which sin and lack of sincerity always obscure the light of reason and conscience.

[p. 257]

The general rules that state the place of conscience in man’s religious and moral life follow from the nature of conscience, and may be thus summarized: (1) One must always follow conscience when it commands or forbids action, and never act against it; (2) one may always follow conscience when it permits action. However, if left in this general statement, these rules would be too general; they would overlook the two great problems which have claimed the attention of moralists for centuries. First, there is the problem of what is called the “dubious conscience,” meaning the state of mind of one whose religious or moral position is not secure, but undermined with doubts, so that, confronted with alternative courses of action, he hesitates in deciding which course is dictated or permitted by reason and the law of God. This famous problem, so actively discussed in more modern times, need not concern us here. Suffice it to say that such a dubious conscience is no rule of right moral action, and that action in such a state of mind would be certainly sinful; for it would be a practical affirmation of indifference toward the law of God, and a wilful exposure of oneself to the risk of offending Him. Of itself, this state of mind imposes the obligation of a search for fuller truth, or, in the last analysis, of recourse to a reflex principle whereby conscience may be “formed” to certitude. Several moral systems have been proposed as means of thus “forming” conscience; the leading one is the system of “probabilism,” as it is called. In some quarters, of course, it is the fashion to dismiss this whole area of moral science (characteristically Catholic) as intolerably subtle and casuistical. As a matter of fact, however, these very practical speculations strikingly exhibit the two concerns that run all through Catholic moral thought. The first is a profound concern for the sacredness of the law of God, which must at all costs be kept inviolate; and the second is an equally profound concern for the integrity of conscience, whose every exigency must be respected and whose inner freedom must be safeguarded.

More pertinent to our present purposes is the problem of the erroneous conscience. It is the older problem of the two; for instance, it is primary among the issues raised by St. Thomas Aquinas when he is discussing conscience. The sheer fact that conscience can be erroneous—that it can command or permit what is actually wrong, and forbid what is actually right—is too obvious to escape anyone who has

[p. 258]

ever thought about conscience. Human reason has almost unlimited possibilities of being deceived, and especially of deceiving itself, notably in its own case, and even more notably in its moral judgments. Men confuse right with wrong, error with truth; and the confusion is nonetheless real because it is oftentimes entirely sincere. A man’s sincerity proves only that he is sincere; it does not prove that he is wise, or even right, for he may be sincerely ignorant or sincerely wrong. Moreover, God has commanded us, not only to be sincere, but to do what is right and avoid what is wrong. The question, therefore, rises, whether conscience can oblige us to do what is wrong or to avoid what is right.

An erroneous conscience, of course, is a practical judgment with regard to religious belief or moral action that is formed in ignorance of the full realities of the case, and that, as a matter of fact, is wrong. So, to take an obvious example, one might judge polygamy to be not only licit but a matter of religious observance, in ignorance of the fact that it is contrary to the natural law. Ignorance is at the root of the error found in the judgment. It follows immediately, therefore, that the moral status of the erroneous conscience will depend on the nature of the ignorance which occasioned it. In general, two types of ignorance may be distinguished.

First, we may suppose the case of a man who is in ignorance, but who has a more or less strong suspicion that he is in ignorance. To some degree, he is conscious of the fact that he is assuming a position that it not entirely reasonable, but rather “rationalized”; he assumes it for reasons that are, as the distinction goes, “good reasons,” but not “the real reasons.” He achieves certainty of a kind, but it is only of the surface; he is at least dimly aware that he has not got to the bottom of the matter. His ignorance is real enough, therefore, but vincible. It can be overcome because it is somehow recognized as ignorance. The defect of knowledge has not escaped the man, and he perceives it as possibly leading to an error of judgment. Yet he makes the judgment, which turns out, in fact, to be erroneous. This, in brief, is the state of what is called the vincibly erroneous conscience. The question is, whether such a conscience is a right norm of moral action.

The answer is, obviously, no. A man may neither follow such a conscience nor act against it, since for all practical purposes it is a “dubious” conscience, that can utter no proper permissions or imper-

[p. 259]

atives. In this state of mind, a man’s single obligation is to rid himself of his ignorance, and get at the realities of the case, by a process of study, consultation, and prayer. In the meantime, action has to be held in abeyance.

Again, we may suppose the case of a man who is in ignorance, but who likewise is not in a position to get out of his ignorance, because he does not suspect that he is in it. His position was reached after serious thought, prayer, and the use of the readily available means of arriving at a right judgment. He is quite secure in thinking that he beliefs he holds are true or that the action he contemplates is good; here is neither doubt nor disquiet nor any thought that he may perhaps be wrong. His ignorance, in a word, is invincible; for the starting point for overcoming it is lacking. Yet the practical judgment, made in consequence of the ignorance, is actually erroneous. What of this practical judgment?

All moralists agree that, if such a conscience permits a particular belief or action, one may licitly follow it, and they agree, too, that if such a conscience commands or forbids a particular belief or action, one is strictly bound to follow it, and not to act against it. The reason lies in the very nature of man. In making human nature rational, God made it subject to the laws of a rational nature; and one of these laws is the general law that all laws of human nature must reach man, and be imposed upon him, by reason and its practical judgments. There is no other way, in keeping with the dignity of man, whereby his obedience to the laws of his nature may be secured, save by these practical dictates of reason, which procure obedience, and a rational obedience. It is, therefore, a law of nature that one of the functions of reason is to mediate the eternal law of God. Reason may, indeed, perform this function badly; it may mistake for law what is not law, and it may be blind to the law that really is law. But, even when performing its function badly, reason cannot destroy its own function, nor alter the general law which makes it the mediator of the will of God. St. Thomas Aquinas had this general law in mind, when he said: “When reason erroneously proposes anything as the precept of God, then to despise the dictate of reason is the same thing as despising the precept of God” (I–II, q. 19, a. 5 ad 2m). He illustrates this principle by an example that has been classic since St. Augustine, as an expression of the role of conscience: “If one were to believe that the

[p. 260]

precept of the proconsul was the precept of the emperor, then, in defying the precept of the proconsul, one would be defying the precept of the emperor.,” Conscience is not, indeed, the “emperor” God; but it is truly a proconsul; and it remains such even when it garbles the emperor’s commands.

Moreover, behind this statement of the role of conscience, even when it is erroneous, there lies a metaphysic of rational nature, which puts reason in an essentially mediatorial position between the will and its object: “Since the object of the will is that which is proposed to it by reason, as I have said, from the very fact that a thing is proposed by reason as an evil thing, the voluntary act, in going out to it, assumes the character of an evil act.” And St. Thomas pushes this conclusion inexorably: “To believe in Christ is in itself a good thing, and necessary for salvation; but the will does not go out thereto, except inasmuch as it is proposed by reason. Consequently, if this belief be proposed by reason as evil, the will goes out to it as evil—not that it is evil in itself, but that it is evil by accident, in the manner of its apprehension by reason.” And St. Thomas concludes with what is the universal law of nature in this matter: “Wherefore it must be asserted, as an absolute principle, that the voluntary act which is out of harmony with reason—whether reason be right or erroneous—is always evil.”

Evidently, therefore, we must speak of two wills of God here. Initially, there is His supreme will that the reason of man and its practical judgments should be in harmony with the eternal order of reason which exists in His divine mind; in other words, God wills that man’s conscience should be always right and true. There is also His will that the voluntary acts of man should be in harmony with own reason and its practical judgments; in other words, God wills that man should act according to his conscience. But at times the two wills of God are not simultaneously observed. In acting according to conscience, man at times acts against the eternal order of reason, being in ignorance of it; his act, therefore, is in harmony with his conscience, but his conscience is not in harmony with the eternal reason of God. This is, of course, an eccentricity in the moral order; which illustrates at once the dignity and the misery of conscience. In the face of it, to keep our moral thinking straight, we must maintain

[p. 261]

two principles. On the one hand, even when conscience is erroneous, it must be followed. On the other hand, even though we must follow an erroneous conscience, it still remains erroneous. These two priniples must be maintained, lest we either assert that conscience is God, or deny that it is the voice of God.

This brings up a further question: If an erroneous conscience must be followed, just as a true conscience must be followed, is the status of the erroneous conscience the same as that of the true conscience? To answer, a distinction has to be made between what I shall call the moral function of conscience and its juridical function. I should explain the distinction as follows. The erroneous conscience, equally as the true conscience, assures the individual that his action is guiltless in the sight of God. For instance, the conscientious, polygamist commits no sin by his polygamy; in the internal order of private morality, his action is good and even meritorious. However, unlike the right conscience, the erroneous conscience does not create any rights that are coactive against legitimate authority, within the field of that legitimate authority, or that could prevail in conflict with the rights of other men. For instance, the conscientious polygamist cannot, under appeal to conscience, claim the right to practice polygamy in an ordered society, in such wise that the prohibition of polygamy by civil law would be injurious—a violation of a right of conscience. To take another example, a man might sincerely believe that it is morally right to steal in order to give alms, and he would be personally guiltless in doing so. But his erroneous conscience creates no right that would induce in his victim a juridical obligation to cede his property, or in the State an obligation to let the theft go unpunished.