Box 33.1 folder 9 of the Michael Amrine Papers (GTM-760826) contains this photograph of Einstein with his secretary Helen Dukas and his dog Chico.

Born in Ulm, Germany, Albert Einstein (1879-1955) is perhaps the most prominent scientist of the twentieth century. He was a university professor in Germany, but he immigrated to the United States in 1932 as the anti-Jewish Nazis were consolidating power. Einstein taught at Princeton University for many years and theorized that great amounts of energy could result from splitting an atom of uranium. In 1939, Einstein wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt urging him to create an atomic bomb before the Nazis did. However, Einstein did not participate in the Manhattan Project, the secret American effort to develop an atomic bomb.

Einstein was traveling when he learned that the US dropped an atom bomb on Hiroshima. He worried that an arms race might ensue as several nations sought to establish programs to build their own nuclear weapons. As a result, Einstein helped establish the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists in 1945 for which he was chairperson until late 1948.

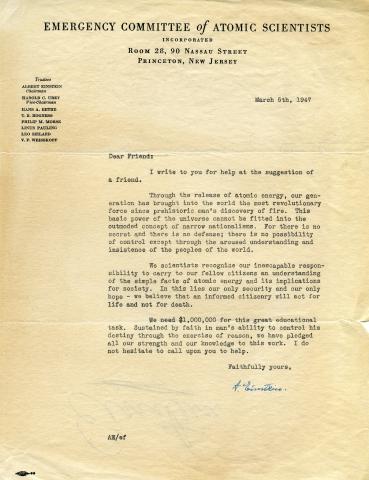

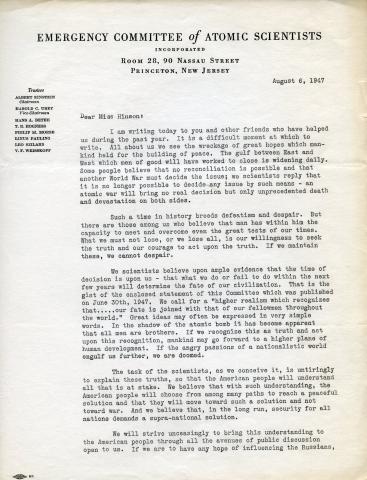

Box 14 folder 32 of the Michael Amrine Papers in the Booth Family Center for Special Collections in the Georgetown University Library contains two letters from Einstein while chairperson of the committee. Michael Amrine (1918-1974) was an American journalist who specialized in atomic energy. He was employed by the Federation for Atomic Scientists and also edited The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists.

In the first letter under consideration, dated March 5, 1947, Einstein addressed the correspondent as "Dear Friend." Einstein wrote on the stationery of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, which was based in Princeton, New Jersey. Einstein wrote: "Through the release of atomic energy, our generation has brought into this world the most revolutionary force since prehistoric man’s discovery of fire." He warned that nation states were not equipped to control atomic power. Instead, he suggested that controlling the spread of nuclear capability could only be accomplished "through the aroused understanding and insistence of the people of this world." Further, he argued that scientists play a key role in informing the public about the nature of atomic energy. Einstein explained that his committee sought 1 million dollars "for this great educational task."

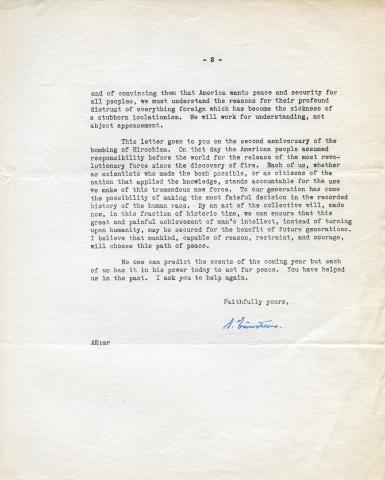

Einstein wrote the second letter, dated August 6, 1947, on the same letterhead. He addressed this letter to "Dear Miss Hinson." He described the current world scene as a "difficult moment" as forces at play threatened world peace with the Cold War between America and the Soviet Union emerging. A third world war would bring no victor, Einstein argued, "only unprecedented death and devastation on both sides." Einstein contended that humanity could "meet and overcome even the great tests of our times."

He claimed that the next few years were crucial and proposed that "in the long run, security for all nations demands a supra-national solution." He hoped that scientists could educate the public in order to promote peace. Einstein noted that this letter was written on the second anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima. He believed that humanity, "capable of reason, restraint, and courage, will choose this path of peace."

These two letters reflect Einstein’s belief that peace was possible if nations joined together to control the spread of nuclear weapons. He thought that a world government was the only way to control atomic energy. As events unfolded, the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic weapon in 1949 and Great Britain acquired the bomb in 1952. The Cold War between the Americans and Soviets lasted for decades. Einstein insisted that scientists had an obligation to inform the public about the dangers of atomic energy.

Scott S. Taylor

Manuscripts Archivist