For a small organization of academically oriented priests, Jesuits have played an outsized role in the history of film, from the science of lenses and projection, to the development of the dramatic arts, to serving as sources of inspiration for Hollywood screenwriters, to defining the ethical content and limits of American film productions.

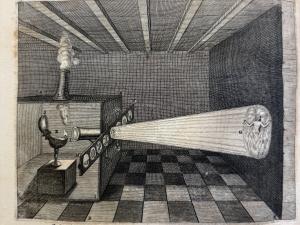

The advent of film can partly be traced to the work of a Jesuit scientist, Athanasius Kircher, S.J. “The Magic Lantern,” an early form of the projector, was first detailed in Kircher’s work Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (1671), The Art of Light and Shadow. It quickly found a home within Jesuit theater productions, popular throughout Europe, and captured the imagination of audiences with fantastical stagecraft, propelling the technology beyond the Society.

Jesuits were not only involved in the historical development of film, but have long been a point of fascination for Hollywood storytellers, with depictions both historical (Silence, Black Robe, The Mission) and fictional (The Exorcist). A number of prominent directors can also claim roots in Jesuit education, such as Alfred Hitchcock, Martin Scorsese, and James Gunn.

Jesuits have also helped define the limits of what film could show. In the 1930’s, pressure from the American public forced Hollywood producers to adopt an ethical code, policing what could be shown on film. Martin Quigley, a publisher of film trade journals and devoted Catholic, tapped Daniel Lord, S.J., to draft what would become known as the Hays Production Code. In drafting the code, Lord was concerned about the potential for mass entertainment to influence the moral character of a nation, and hoped to root film in the morality of the Ten Commandments. By the 1960s, the American moral, religious, and artistic landscape had shifted, and, ironically, it would be Jesuits like John Courtney Murray, S.J., who would develop arguments against censorship in a pluralistic society that would pave the way to the Code’s demise, opening the medium to new artistic avenues.

Curated by Adrian Vaagenes, Woodstock Librarian

Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae

Athanasius Kircher, S.J.

Amsterdam, Netherlands 1671

Booth Family Center for Special Collections - Rare Book Collection: Cube Folios Q155 .K56 1671

The history of the movies can partly be traced back to the great Jesuit scientist Athanasius Kircher, S.J., whose experiments with lenses led to the discovery of what became known as “the Magic Lantern.” Kircher found that by using a transparent image backed by a light source, and focused with a lens, he could project an enlarged image. Kircher was also said to have developed a rotating wheel of successive images to tell a story, essentially inventing the rudiments of film and animation 350 years ago. Jesuits took to the new technology, using it for catechesis and in their school theater productions.

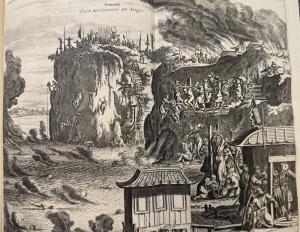

Ambassades mémorables de la Compagnie des Indes Orientales des Provinces Unies, vers les empereurs du Japon

Arnoldus Montanus

Amsterdam : Chés Jacob de Meurs, Merchand sic libraire, 1680

Booth Family Center for Special Collections - Rare Book Collection: Vault Folios DS808. M77 1680

The Jesuit missions have long been a source of inspiration for Hollywood storytellers, most notably in Black Robe (1991), The Mission (1986), and most recently in Martin Scorsese’s Silence (2016). Based on the novel by Shusako Endo, the movie depicts the 17th century persecution of Japanese Christians, following two Jesuits as they minister to hidden Christian communities as they face torture and death. This violent history was captured in Ambassades Mémorables, a history of Japan based on Jesuit accounts and displayed here.

Photographs of Martin Scorsese and David Collins, S.J., While on Tour of the Church of the Gesù

Provided by David Collins, S.J.

David Collins, S.J., a historian at Georgetown, served as a consultant to Martin Scorsese during the making of Silence. While showing the film at the Vatican for Pope Francis, Collins gave a tour to Scorsese of the Church of the Gesù, the mother church of the Society of Jesus. Jesuits not only served as historical consultants, but guided the actors as well. James Martin, S.J., instructed the lead Andrew Garfield on the Spiritual Exercises in preparation for making the film.

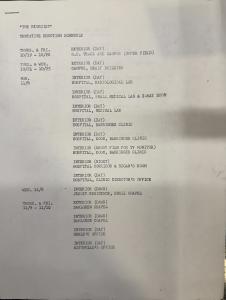

The Exorcist VHS tape, and Warner Brothers Shooting Schedule

David Collins, S.J., a historian at Georgetown, served as a consultant to Martin Scorsese during the making of Silence. While showing the film at the Vatican for Pope Francis, Collins gave a tour to Scorsese of the Church of the Gesù, the mother church of the Society of Jesus. Jesuits not only served as historical consultants, but guided the actors as well. James Martin, S.J., instructed the lead Andrew Garfield on the Spiritual Exercises in preparation for making the film.

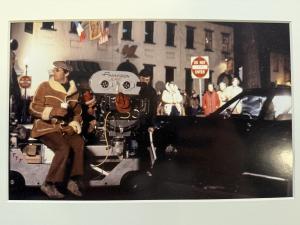

Photo of Director William Friedkin along Prospect St. on the Set of the Exorcist

Gift of Professor Emeritus Clifford Chieffo

Original Copy of the Hays Production Code; The Motion Pictures Betray America, Pamphlet

Daniel Lord, S.J.

1930

Booth Family Center for Special Collections - Georgetown Manuscripts, Martin Q Quigley Collection, Box 2, Folder 23; Box 1, Folder 18

While Jesuits have often been recognized for their role in the technological history of film, their role in Hollywood censorship is frequently forgotten. In 1930, under pressure from both the public and the state to police the content of its pictures, Hollywood tapped Daniel Lord, S.J., to write what became known as the Hays Production Code (Original copy on display). Lasting from roughly 1935-1960, the Code served to define what was allowed to be seen on screen for a generation of Americans. In a historical irony, Jesuits were also a part of its eventual downfall, with Jesuits such as John Courtney Murray, S.J., making the Catholic case against censorship.