This exhibition highlights some of the stories and themes explored by Professor Maurice Jackson in Rhythms of Resistance and Resilience: How Black Washingtonians Used Music and Sports in the Fight for Equality, published by Georgetown University Press in 2024. Music and sports have been vital to Black self-expression and survival, becoming a source of pride and joy and a means of demonstrating Black excellence. Overcoming the rigid segregation and inequality of Washington, D.C., Black musicians and athletes provided a powerful counterpoint to racism and used their popularity among white audiences to bring attention to cultural bias and systemic injustices.

Incubator of Great Black Music

The nation’s capital is known for both its large Black population with roots from the deeper South and its role as an international city of monumental grandeur. The Janus-faced nature of the nation’s capital proved important in the development of jazz. Some of the early greats, most famously Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington, cut their teeth on the Black music performed on the streets and in music halls in Washington, D.C. For others, notably Marian Anderson, Washington proved to be a singularly important stage that drew international attention to Black achievement and the rigid segregation of Washington. The culture created by these early jazz musicians is evident in the numerous music clubs and tributes to them in present-day Washington.

James Reese Europe and Black musicians play jazz for wounded American soldiers and the people of France outside a hospital, 1918

At the age of ten, James Reese Europe and his family moved into the D.C. neighborhood of the Marine Corps band leader John Philip Sousa, a fortuitous coincidence that led Europe to become a musical composer and band leader who popularized Great Black Music internationally. After receiving his musical education from Dunbar High School and taking lessons from members of Sousa’s band, Europe moved to New York City where he adapted the marching band style and ragtime to play an early form of jazz.

In 1917, Europe accepted a commission as an officer and leader of the regimental band for the 369th U.S. Infantry Regiment, an all-Black unit whose heroic defense of the French border from German invasion earned them the moniker “Harlem Hellfighters.” Its band played its jazzy marching band music in front of British, French, Italian, and American audiences to great acclaim. At the end of a United States tour of the Hellfighters Band, on May 10, 1919, a disgruntled band member fatally stabbed James Reese Europe. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Photograph by U.S. Army Signal Corps

Library of Congress

The 369th U.S. Infantry led by James Reese Europe, “Memphis Blues,” performed at an opera house in Nates, Italy, 1918. James Reese Europe's 369th U.S. Infantry "Hell Fighters" Band Complete Recordings, Inside Sounds, 2005

Marian Anderson performs in front of 75,000 people at the Lincoln Memorial, April 9, 1939

An open-air concert on the Mall by internationally celebrated contralto Marian Anderson (1897-1993) exposed Washington's segregated society to the nation. In 1939, Anderson and her promoters sought access to Constitution Hall, owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), for what had become an annual concert by Anderson for Washington audiences. Enforcing a “white artist only” clause in its leasing agreement, the DAR denied access to the venue. After First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt showed her support of Anderson by resigning her DAR membership, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes arranged for Anderson to perform on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. At a performance that drew national attention, Anderson sang songs from the Black spiritual tradition and “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” (“America”) to advance a vision of an inclusive society.

Photograph by Robert S. Scurlock

Smithsonian Institution Museum of American History

Newsreel, “Marian Anderson Sings at Lincoln Memorial," April 9, 1939. Hearst Metrotone News Collection, UCLA Film & Television Archive.

Duke Ellington and his band at the Howard Theater, 1940

By the time of this 1940 performance at the Howard Theater, Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899-1974) was a nationally prominent performer known for his expressive instrumental jazz compositions. His childhood in rigidly segregated Washington shaped his art, as his music reflected his educational influences and his sensitivity to sharp class differences associated with skin color, a salient characteristic of Black Washington. His move to New York City in 1923 enabled him to reach white and Black audiences. In January 1943, Ellington debuted his extended jazz symphony Black, Brown, and Beige at Carnegie Hall, a work meant to convey the history of African Americans to the cultural elite of New York.

Photograph by William P. Gottlieb

Library of Congress

Duke Ellington, Black, Brown, and Beige, 1958. Recording with Mahalia Jackson, Jazz Time with Jarvis.

Jazz performance at the Turkish Embassy, c. 1940

Ahmet and Nesuhi Ertegun, sons of the Turkish ambassador to the United States, helped to smash the social boundaries of segregated Washington, D.C. The Ertegun brothers brought their love of jazz, first cultivated in London, to Washington. Beginning in 1940, the brothers began to invite integrated audiences to the Turkish Embassy on Massachusetts Avenue to listen to performances by Black musicians – including Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne, Joe Marsala, and Jelly Roll Morton. Beginning in 1942, the Ertegun brothers began to promote concerts for integrated jazz orchestras for mixed audiences, first at the Jewish Community Center and then at the National Press Club.

The ensemble photographed at this Turkish Embassy jam session included members of the Ellington and Marsala bands: Johnny Hodges (partially hidden in back), Rex Stewart, unidentified saxophonist, Harry Carney, Adele Girard, Barney Bigard, unidentified person (in back), and Joe Marsala.

Photograph by William P. Gottlieb

Library of Congress

Duke Ellington celebrating his 70th birthday at the White House, April 29, 1969

During the presidencies of Lyndon Baines Johnson and Richard M. Nixon, Duke Ellington frequently performed at the White House, located only ten blocks from his birthplace. On his 70th birthday, President Nixon recognized Ellington’s musical achievements, which included several goodwill tours under the auspices of the State Department, by awarding him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Photograph by Jack Kightlinger

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum

The Listening Group gathers in front of the Duke Ellington mural, c. 1992

In the early 1980s, Maurice Jackson (photographed in back row, center) joined a newly formed club of jazz aficionados, known as the Listening Group. The members came together monthly to share their appreciation of the Washington jazz scene. This fraternity extends beyond listening sessions and discussions centering on established and emerging artists, as the group has advocated for historic jazz venues to remain open.

In this photograph, members of the Listening Group stand in front of a mural on 1214 U Street, N.W., composed by G. Byron Peck, that memorializes Duke Ellington. The mural has since been moved to the True Reformers Building on 1200 U Street, which a Black fraternal organization commissioned in 1902. In the winter of 1917 and 1918, Ellington’s first band, “The Duke’s Serenaders,” staged its first paid performance in the True Reformers’ dance hall.

Listening Group members (front row, left to right): Howard McCree, Sam Turner, Joe Selmon, Fred Foss, Keith Hunter, Tom Porter, unidentified person, Bill Brower, and Michael Wallace. (Middle row, left to right): John Whitmore, Tariq Tucker, Bill Shields, Aminifu Harvey, James Early, Gaston Neal, Norville Perkins, Phil Roane, Lew Marshall, Ron Clark, Medaris Banks, and David Truly. (Back row, left to right): Askia Muhammad, Willard Jenkins, Maurice Jackson, Wilmer Leon, Muneer Nassar, Elijah “Smitty” Smith, Ralph Matthews, Michael Thomas, and Barry Carpenter.

Courtesy of the photographer Marvin Tupper Jones

Maurice Jackson Papers, Booth Family Center for Special Collections

Pearl Bailey celebrates her Georgetown graduation with Philosophy professor Wilfrid Desan, May 1985

After receiving an honorary degree at the 1977 commencement, well-known stage singer Pearl Bailey (1918-1990) enrolled at Georgetown to earn her bachelor's degree in Theology. When she was three years old, her family moved to Washington, but she spent most of her formative years with her mother in Philadelphia. Nonetheless, the clubs on U Street, known as “Black Broadway,” helped launch her career.

Georgetown University Archives

The Shirley Horn Trio at the benefit for the Free Festival at the Duke Ellington School for the Arts, November 3, 1989

Born and bred in Washington, D.C., Shirley Horn studied classical piano at Dunbar High School and the Howard University Junior School of Music. Instead of taking offers to continue her education in New York, Horn chose to marry and raise her daughter in Washington. Nonetheless, she continued to form bands and attracted the attention of leading musicians by concentrating on local venues. After she recorded her first album Embers and Ashes in 1960, she accepted the invitations of jazz trumpeter Miles Davis to tour and record with him. As her schedule allowed, she began touring with her band outside the D.C. area, especially in Europe. Despite international acclaim, which included the 1999 Grammy Award for Best Jazz Vocal Performance, she remained loyal to her band and stayed active in the Washington music scene.

In this photo, Horn (vocals and piano) is photographed with members of her band, Charles Able (bass) and Steve Williams (drums), and their guest, Roger “Buck” Hill (saxophone).

Courtesy of the photographer Michael Wilderman

Shirley Horn & Miles Davis, "You Won't Forget Me," 1990. LaTramaDeLosCielos.

Pianist Jason Moran leads multimedia performance “Harlem Hellfighters: James Reese Europe and the Absence of Ruin,” 2021

Jason Moran, Artistic Director for Jazz at the John F. Kennedy Center for Performing Arts from 2011 until his resignation in 2025 and Distinguished Artist in Residence at Georgetown between 2017 and 2018, initiated a musical and visual exploration of the life of James Reese Europe and his band “Harlem Hellfighters.” His project culminated in an international tour of “Harlem Hellfighters: James Reese Europe and the Absence of Ruin,” his interpretation of their music and its impact on jazz history, which included a video depiction of sites and graphics associated with Europe and his band.

Courtesy of the photographer Jati Lindsay

Jason Moran, "James Reese Europe and the Harlem Hellfighters: The Absence of Ruin," 2021. The Kennedy Center.

Buck Hill, the “Wailin’ Mailman,” memorialized on 70-foot mural on U Street, 2018

Saxophonist Roger “Buck” Hill (1927-2017) was a link between the days of rigid segregation in Washington, D.C., and the more modern form of today. He attended Armstrong High and began playing professionally in 1943, one year before he enlisted in the U.S. Army. After he married in 1949, Hill took a job as a letter carrier, a day job he kept until 1998. He balanced this role with his musical career by performing in local clubs and taking weekend gigs in New York and other places. Painted by Joe Pagac for the DC Murals Project in 2018, the Buck Hill mural is located on 1925 14th Street, N.W.

Courtesy of the photographer Ron Cogswell

Sports as the Great Unifier

Black Washingtonians embraced sports to promote their well-being, entertain themselves, and puncture racist assumptions regarding their athletic abilities. The owners of the Washington Senators and Washington Redskins (now Commanders) accepted a competitive disadvantage by refusing to sign African American players after other teams across the country integrated Black players into their ranks during the late 1940s. This exclusion did not prevent Black Washingtonians from establishing community organizations that encouraged children to play and excel in sports. When Black athletes led the Washington Redskins and the Georgetown Hoyas to championships during the 1980s, Washington sports fans celebrated joyously.

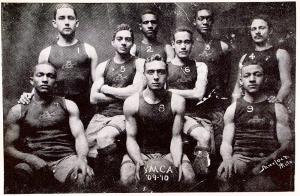

The Washington Twelfth Streeters, 1909-1910

The undefeated 1909-1910 champions of the “Colored Basketball World” represented the Twelfth Street Colored YMCA and used the dance hall in True Reformers Hall as their home court. Seated in the center of this photograph with the basketball, their 5’10” center Edwin Bancroft Henderson (1883-1977) played a pivotal role in ensuring that Black women and men could maintain physical fitness, compete in basketball, and provide entertainment to fans.

Henderson’s vision originated during his course of study at the Harvard Summer School of Athletics between 1904 and 1907. As he was completing that program, he began to organize basketball referees and the first African-American Athletic League (ISAA), institutions that became essential to the growth of basketball in Washington. After he finished playing with the Twelfth Streeters in 1910, he served as director of the Department of Physical Education for the District of Columbia’s segregated Black schools for twenty-five years. Called the “Grandfather of Black Basketball,” Edwin B. Henderson was enshrined into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in 2013.

Photograph by Scurlock Studios

Courtesy of E.B. Henderson III

Official Hoophall, "E.B. Henderson's Basketball Hall of Fame Enshrinement Speech," September 9, 2013. Basketball Hall of Fame.

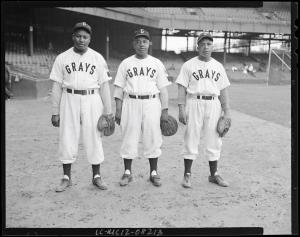

Three members of the Homestead Grays at Griffith Stadium, January 9, 1947

One of the best teams in the Negro Leagues, the Homestead Grays split their home games between Forbes Field in Pittsburgh and Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C. This photograph of Josh Gibson (1911-1947), Ted “Double Duty” Radcliff (1902-2005), and Euthumn "Eudie" Napier (1913-1983) was taken only three months before Jackie Robinson debuted as the first Black player in the major leagues. Three-time Negro League World Champions in 1943, 1944, and 1948, the Homestead Grays often attracted larger crowds than the major league Washington Senators. Their owner, Clark Griffith, vehemently opposed major league integration because of his racism and his unwillingness to give up the profits garnered from the Homestead Grays’ games. The Washington Senators did not have an African American player until 1957.

Eleven days after posing for this photograph, on January 20, 1947, Josh Gibson died of a stroke in Pittsburgh, abruptly ending the career of one of baseball’s all-time best players. Recognized as one of the most powerful hitters to have ever played baseball, the Negro Leagues Committee voted Gibson into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1972. After Major League Baseball integrated the statistics of Negro League players into its record books in 2024, Josh Gibson topped the hitting records for the highest season batting average (.466 in 1943) and highest career batting average (.371).

Photograph by Robert H. McNeill

Library of Congress

Super Bowl Victory Parade on Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., February 1988

This parade celebrating the 1987 Washington Redskins was a rare celebration that brought together white and Black fans from all parts of the city. Leading the second of three Super Bowl victories between 1983-1992, Doug Williams – the first Black quarterback to start and win the Super Bowl – completed 18 of 29 passes for 340 yards with four touchdown passes to win the Super Bowl Most Valuable Player award. His performance was long-awaited, as Washington was the last NFL team to take Black players, since its owner George Preston Marshall thought an all-white team would enhance Washington’s marketability in the South.

Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith

Library of Congress

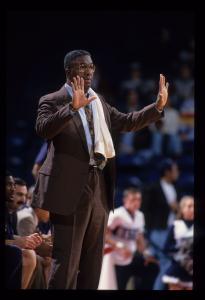

John Thompson, Jr., on sideline with trademark white towel, 1993

At every single game he coached, the towering figure of John Thompson, Jr., draped a white towel on his shoulder as a tribute to his father John Thompson, Sr., and his mother Anna Thompson, who wore a towel over her shoulder in the Thompson family kitchen. Her commitment to education and her tireless advocacy for his well-being enabled him to overcome his early childhood struggles with reading.

A standout center for city champions Archbishop Carroll High School, he used basketball both to compete at the sport’s highest level and to gain an education. After graduating from Providence College in 1964, he played as backup center to Bill Russell on the Boston Celtics. In 1966, he took a job coaching at St. Anthony’s High School, while he earned his master’s degree in Counseling and Guidance at Federal City College (now the University of the District of Columbia). When Georgetown hired him in 1972, Coach Thompson committed himself to educating his players and to exceeding the competitive expectations of the administrators who hired him.

Georgetown University Archives

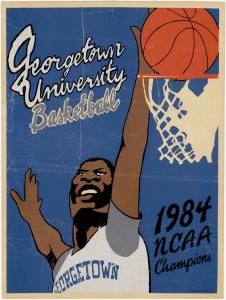

Championship Poster celebrating the Hoyas and center Patrick Ewing (C ‘1985)

Designed and produced by Georgetown student Christian “Chris” Simms, this poster captured the excitement of the predominantly white campus community for the Hoyas’ first NCAA Championship. This enthusiasm was shared by Black Americans whose pride in the Hoyas’ victory was similar to that felt when Jackie Robinson broke the color line in baseball and Joe Louis won the heavyweight title. The first Black coach to win a NCAA Championship title, Thompson led a group of men who embraced their Black identity, even as they represented an elite Catholic school that admitted relatively few Black students.

Screen Print by Christian Simms (C ‘1984)

Gift of Bennie Smith (C ‘1986)

Georgetown University Archives

Maker of Men

John R. Thompson, Jr became the head basketball coach at Georgetown University in 1972, a school that did not recruit him as a player in 1960 because of his race. In the aftermath of the 1968 uprising in Washington, D.C., administrators hoped that Thompson could help improve community relations with the Black residents of the city. Committed to providing educational opportunities and developing a winning program, Thompson used his voice to protect his players from racist taunts, which came from Georgetown students, at venues across the country, and through the media.

At the 1982 Final Four in New Orleans, a reporter asked Thompson how he felt to be the first Black coach to reach the Final Four. He answered:

I resent the hell out of that question. It implies that I am the first Black coach capable of making the Final Four. That’s not close to true. I’m just the first one who was given the opportunity to get here.

During his successful 17-year tenure – which included 20 NCAA appearances, including 3 NCAA finals and the 1984 championship – Thompson used his platform to advocate for equal educational opportunities for all Black athletes, not just his own players. His full-throated advocacy, as exemplified by his statement during the 1982 Final Four, helped the Georgetown Hoyas become a household name nationwide and earn the fervent support of Black Americans.

Craig “Sky” Shelton during the Big East semi-final game, February 29, 1980

The inaugural year of the Big East Conference, the 1979-80 season was also the breakout year for the Georgetown Hoyas. A team composed mostly of recruits from Washington, D.C., who were largely overlooked by leading college programs, the Georgetown Hoyas crashed into the national conversation by beating the highly-favored Syracuse Orange during its final game at Manley Field House, where it had held a home winning streak of 57. The Hoyas then won the first of their eight Big East Tournaments, with Washington, D.C., native and Dunbar High School graduate Craig Shelton winning the Tournament Most Valuable Player Award. The Hoyas advanced to the Elite Eight of the NCAA Tournament, losing to the Iowa Hawkeyes.

Georgetown University Archives

Patrick Ewing emphatically dunks over UVA center Ralph Sampson during the “Game of the Decade,” December 9, 1982

Seeking to build upon the excitement of the 1982 NCAA Tournament that ended with the Hoyas losing to the University of North Carolina Tar Heels in the finals, television networks aggressively bid to air a game between the Hoyas, led by center 7’ Patrick Ewing, and University of Virginia, led by 7’4” Ralph Sampson. A new cable station at the time, TBS, won the rights to this game, which was held at the Capital Center in Landover (home court of the Washington Bullets) on December 9, 1982. Billed as the “Game of the Decade,” the showdown not only cemented Georgetown’s status as a national powerhouse but also elevated college basketball as a prime-time sport. Ewing’s thunderous dunk over Sampson (photographed here) represented the climax of the game, which ended with a 68-63 Hoyas’ loss.

Georgetown University Archives

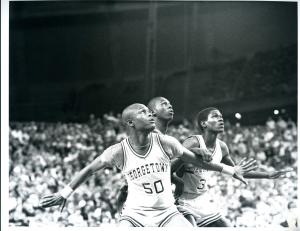

Freshman stars Michael Graham and Reggie Williams in position to grab a rebound, 1984

The depth of the 1984 Hoyas enabled freshman forwards Michael Graham and Reggie Williams to ease into their roles, yet both played critical roles for the championship team. During his only year as a Hoya, Graham emerged as the Hoyas’ enforcer during the Big East Tournament. His physical play and rebounding typified the bruising style of play that characterized the Hoyas. A high school All-American from Baltimore’s Paul Laurence Dunbar High School who became a four-year player for the Hoyas, Williams’ mid-range jumper, quick drives to the basket, and tenacious defense proved critical in the 1984 title game against Houston.

Georgetown University Archives

Coach John Thompson walks off the court to protest Proposition 42, January 14, 1989

At the beginning of the Georgetown Hoyas’ home game against Boston College on January 14, 1989, Coach Thompson took the white towel off his shoulder, handed it to Assistant Coach Craig Esherick, and then walked off the court to protest the passage of Proposition 42 by the NCAA. This rule required students receiving athletic scholarships to hold a 2.0 GPA or 700 SAT, a standard that was unfair for Black students who did not have the same educational opportunities as most white students due to the residual effects of segregation. The NCAA feared that Thompson’s boycott would lead other coaches to walk out, so the NCAA suspended the rule by January 20.

Georgetown University Archives

Alonzo Mourning checks in with coaching staff during the 1992 Big East Tournament

Photographed here with his coaches – John Thompson, Mike Riley, and Craig Esherick – center Alonzo Mourning dominated during his senior year and became the first player to win the Big East regular season MVP, Defensive Player of the Year, and Big East Tournament MVP. During his freshman year, Thompson took bold action to protect Mourning. Rayful Edmond, a drug dealer who introduced crack cocaine into the illegal drug market, had befriended Mourning and one of his teammates, John Turner. Thompson warned his players that they could lose their scholarships and confronted Edmond during a face-to-face meeting that drew Thompson into police investigations of Edmond’s drug operations. Edmond promised Thompson that he would stay away from his players, a pledge that he kept.

Photograph by Lee Hobson

Georgetown University Archives

Dikembe Mutombo stuffs the basket, c. 1990

A 7’2” center born in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) who was fluent in nine languages, Dikembe Mutombo arrived at Georgetown in 1987 and spent his first year acclimating to English and university life. During the next season, he played with freshman Alonzo Mourning. This unusual pairing of big men earned them the moniker “Twin Towers” and solidified Georgetown’s reputation as “Big Man U.” Mutombo’s skills as a rebounder and shot blocker led to a 17-season career in the NBA. Known for his international humanitarian efforts, including the construction of a 300-bed hospital in the Congo, Mutombo died of glioblastoma on September 30, 2024.

Georgetown University Archives

Allen Iverson with Coach Thompson, c. 1995

Perhaps the purest athlete to have ever played men’s basketball at Georgetown, 6-foot guard Allen Iverson changed the style of Hoyas’ basketball. His speed, ball-handling, and scoring ability transformed the Hoyas into a fast-paced, high-scoring team.

Intense media scrutiny followed Iverson throughout his career. In February 1993, during his sophomore year at Bethel High School in Hampton, Virginia, Iverson and his teammates were bowling when a fight broke out that ultimately led to injuries among three people. Arrested with four other Black students, Iverson was charged and convicted as an adult of felony “maiming by mob,” even though video evidence revealed he had left before the fight began. Iverson served four months of a fifteen-year sentence in a correctional facility after Virginia’s first and only African American Governor Douglas Wilder granted him clemency.

When he was still in detention, Iverson’s mother approached Thompson to ask him to help her son get to college and start a new life. The next time Iverson played competitively, he played in the 1994 Kenner League in McDonough Gym, captivating an overflow crowd. During away games, racist taunts directed at Iverson were common. At Villanova, fans wore black-and-white prison garb, with one holding a sign, “Iverson: the Next O.J.” After Coach Thompson threatened to pull his players off the court, such visible and public incidents never happened again while Iverson played in college.

Georgetown University Archives

Professor Maurice Jackson teaches in the History, Black Studies, and Music Departments on Georgetown’s Hilltop and Qatar campuses. Rhythms of Resistance and Resilience evinced his love of music and sports as a source of joy for his family and community. The book also reflects his expertise in African-American Social and Intellectual History, Atlantic History, Jazz and Cultural History, Global Cities, and the history of Washington, D.C.

Jackson is the author of Let This Voice Be Heard: Anthony Benezet, Father of Atlantic Abolitionism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009). With Blair Ruble, he is the editor of DC Jazz: Stories of Jazz Music in Washington, DC (Georgetown University Press, 2018). Jackson wrote the liner notes to the two jazz CDs by Charlie Haden and Hank Jones, Steal Away: Spirituals, Folks Songs and Hymns and Come Sunday. He was appointed by the Mayor and the D.C. Council as Inaugural Chair of the D.C. Commission on African American Affairs (2013-16) and presented “An Analysis: African American Employment, Population & Housing Trends in Washington, D.C.” to the Mayor and elected leaders of the D.C. government in 2017. Jackson is completing work on Halfway to Freedom: The Struggles and Strivings of Black Folk in Washington, DC to be published by Duke University Press in fall 2026.

The Library is also grateful to Mary Beth Corrigan, Beth Marhanka, and Bailey Payne for their work curating and producing this exhibition.