February 25, 2021

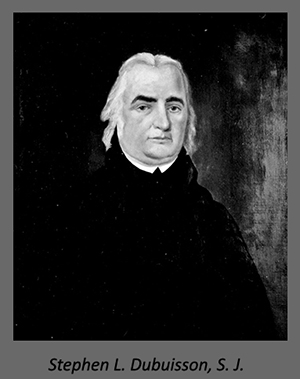

Early in this Black History Month, Woodstock Theological Archivist Adrian Vaagenes alerted me to a journal entry in the papers of Stephen Dubuisson, S.J., part of the Maryland Province Archives held here at Booth.

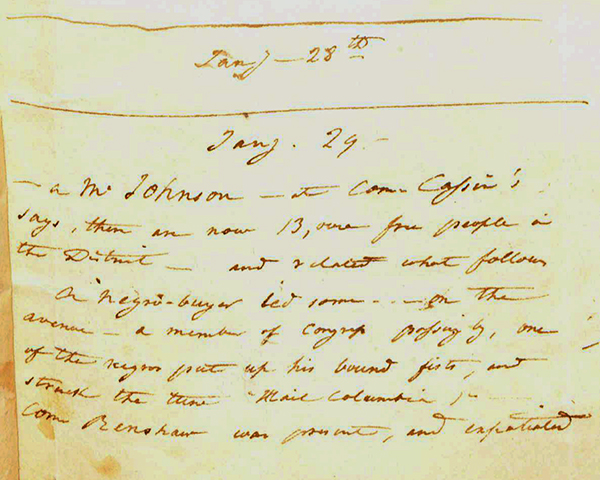

In an entry in his journal on January 29, 1832, Jesuit priest Stephen Dubuisson related the following incident, witnessed by an acquaintance on an unnamed street in the District of Columbia:

In an entry in his journal on January 29, 1832, Jesuit priest Stephen Dubuisson related the following incident, witnessed by an acquaintance on an unnamed street in the District of Columbia:

“A negro-buyer led some [enslaved people]… on the avenue. A member of Congress passing by, one of the negroes put up bound fists, and struck the tune ‘Hail Columbia.’”1

A second witness told Father Dubuisson of “the horribleness of the scene.” Yet another stated that there were “now 13,000 free people in the District” — a crude estimate of the number of free Blacks in the city. No mention was made of the number of enslaved individuals; it is possible that the speaker, like many white people, may have found the growing population of free Blacks to be alarming.2

The scene Dubuisson described is striking, of course, because of its visibility and its location: a slave trader leading people, either recently purchased or about to be sold, down a busy avenue in the young country’s central seat of government. This may have been near our present-day Mall, an area that at the time contained several slave pens.

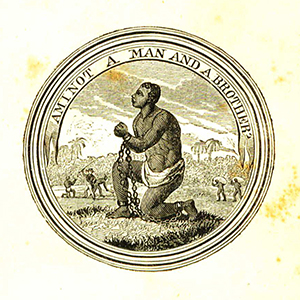

But far more arresting are the specific actions of the enslaved man: described as raising his bound fists in the air and singing “Hail Columbia” so that a passing congressman must hear him and confront the physicality of his enslavement. The raised fists may have called forth the printed image of the “supplicant slave” — a kneeling Black man, bound wrists clasped and held up high, accompanied by the caption “am I not a man and a brother?” — which had been circulating in antislavery circles since the late 18th century.3 Yet in Dubuisson’s short description, there is suggestion that the man’s fists were raised not in supplication, but in defiance, forcing viewers (including a congressman) to contend with the horror of both his literal and figurative shackling.

From John Greenleaf Whittier's

Poems written during the progress of the abolition question in the United States,

between the years 1830 and 1838.

Rare Book Collections, Levy PS3250.37

And then there was the man’s choice of song. For much of the 19th century, “Hail Columbia” operated as the de facto national anthem, describing the country’s hard-won independence and the ensuing sweetness of liberty, brotherhood, and freedom from figurative bondage — none of which would have been available to enslaved people, who as property were denied legal personhood, let alone the rights of republican citizenship.

Further, by the middle of the century, antislavery activists were using — and frequently reworking — the lyrics of “Hail Columbia” to illustrate the hypocrisy of American freedom in relation to slavery.4 In an 1861 edition of the antislavery newspaper The Liberator, for example, the song was reimagined with these opening lines: “Hail, Columbia, traitor’s land! Hail, ye negroes, captive hand…”5

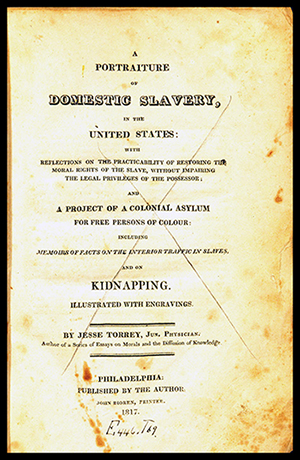

The entry in Father Dubuisson’s journal makes clear that “Hail Columbia” was not just a tool of savvy publishers in the throes of the mid-century antislavery movement, but was in fact used by enslaved people in the early 1830s — as the antislavery press was just beginning — to publicly protest their condition. This is corroborated in the early (1817) antislavery publication by the white physician Jesse Torrey, who related a very similar scene, described to him by a member of Congress, in which “a drove of manacled colored people were passing by” the Capitol when one raised his chains “as high as he could reach” and “commenced singing the favorite national song, ‘Hail Columbia! Happy land….’”6

The fact that Stephen Dubuisson, a prominent white Jesuit and former president of Georgetown College, noted this incident in his journal also deserves examination. Dubuisson’s life was deeply entangled with the Atlantic slave trade and the labor of enslaved people. The son of slave-owning Creoles in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), he and his family fled the colony for France in 1791, just before the outbreak of the “uprising” that would become the Haitian Revolution. As a young man, he became a Jesuit novitiate in 1815 at White Marsh, a tobacco plantation in southern Maryland that had, since the 1760s, been home to more enslaved people than any other Jesuit residence.

After a short stint as the president of Georgetown College in the 1820s, Dubuisson served as pastor at several churches in D.C., Maryland, and Philadelphia, where his parishioners would have included both free and enslaved African Americans, as well as French slave-owning families who, like his own, had fled Haiti for the United States. And in 1836, Dubuisson revealed his thoughts on slavery. In a manuscript held by Archivum Romanum Societatatus Iesu and transcribed by the Georgetown Slavery Archive, he explained that while caring for slaves was difficult, and while the slaves themselves were often “excessively bad,” the Jesuits should neither sell the nearly 300 individuals they owned, nor should they free them, as “free negroes do not know where to go” and would be unable to deal with the “miseries and dangers” of life outside of bondage. (This was just two years before the Jesuits sold 272 enslaved individuals to traders in Louisiana.)7

While it may not be possible to find out more about the specific incident noted in Stephen Dubuisson’s journal, we do know that this was not an isolated incident; as Curator Mary Beth Corrigan notes, there were numerous crowded slave pens near the Capitol, the District of Columbia had “the most active slave depot in the nation,” and we have firsthand accounts of similar acts of defiance.8 Further, both the enslaved man who “hailed Columbia” in protest, and the free Jesuit who documented this action, reveal that the dichotomy of slavery and freedom permeated all aspects of life in the young nation’s capital. Moreover, enslaved people visibly and vehemently rejected their confinement, and in doing so, they established the parameters of its eventual dismantling.

--Cassandra Berman, Archivist for the Maryland Province Archives

Notes:

Notes:

- Maryland Province Archives, Box 12, Folder 3.

- For a discussion of white fear of the free black population in the District of Columbia, see Mary Beth Corrigan, “The Ties That Bind: The Pursuit of Community and Freedom among Slaves and Free Blacks in the District of Columbia, 1800-1860," in Southern City, National Ambition: The Growth of Early Washington, D.C. (Washington, DC: George Washington University, 1995).

- This image, which became one of the most iconic of the transatlantic antislavery movement, originated on a medallion made by British pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgewood in 1787.

- Laura Lohman, Hail Columbia!: American Music and Politics in the Early Nation (Oxford University Press, 2020), 277.

- “Hail, Columbia!” The Liberator (April 19, 1861).

- Jesse Torrey, A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery (Philadelphia, 1817), p. 44. (See title page above. Rare Book Collections 94A284.) Thank you to Mary Beth Corrigan for alerting me to this incident, which is also quoted in her article “Imaginary Cruelties? A History of the Slave Trade in Washington, D.C.” Washington History, vol. 13 no. 2 (2001-2002), p. 5.

- “Dubuisson Memorandum” (1836), Provincia Maryland 1005, II, 4, pp. 1-8, Archivum Romanum Societatis Jesu.

- Mary Beth Corrigan, “Imaginary Cruelties? A History of the Slave Trade in Washington, D.C.” Washington History, vol. 13 no. 2 (2001-2002), p. 5.