June 12, 2020

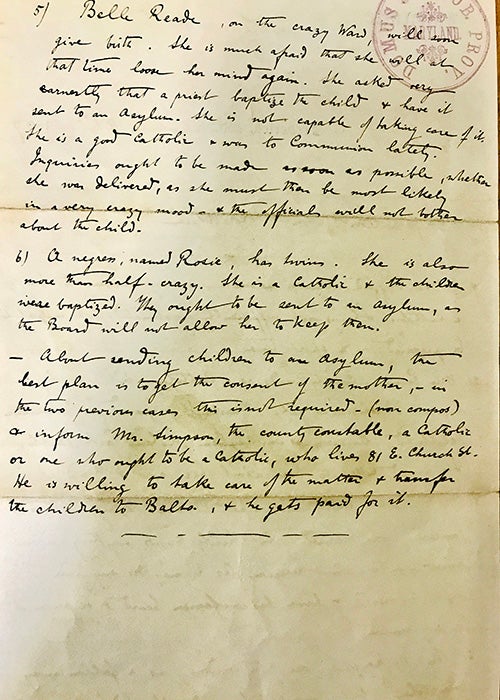

"Belle Reade, on the crazy ward, will soon give birth.

She is much afraid that she will at that time loose [sic]

her mind again. She asked very earnestly that a priest

baptize the child & have it sent to an asylum. She

is not capable of taking care of it. She is a good Catholic

& was to Communion lately. Inquiries ought to be made

as soon as possible, whether she was delivered,

as she must then be most likely in a very crazy mood -

& the officials will not bother about the child."

When I began my position as the Archivist for the Maryland Province Archives (MPA) at Georgetown University, I did not expect to find many women in the collection. The MPA documents the presence of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) in North America from the 17th through 20th centuries. I knew it would be a fascinating collection, but I also assumed that most of the figures I would meet would be male. I thought that I might encounter women in religious orders, or that I would read here and there of a woman who had provided excellent service to the Church. I did not, however, expect to find Belle Reade, a vulnerable woman on the cusp of motherhood and on the margins of society.

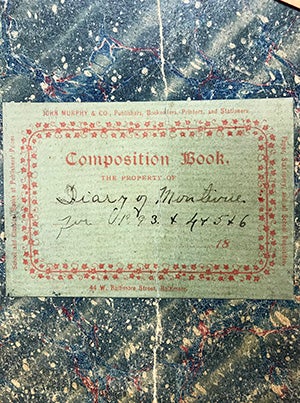

During my first week at the Booth Family Center for Special Collections, I stumbled upon four bound items labeled “Diaries of Montevue.” Dating from the 1890s, these station diaries chronicled the experiences of Jesuit novitiates serving the Catholic inmates at Montevue Asylum in Frederick, Maryland. Inserted into one of these volumes was a loose page titled “Information about Montevue,” dated June 21, 1897. It contained the brief account of Belle Reade, above. Reade, who may have suffered from postpartum depression after a previous birth, seems to have been so worried about her state of mind after her impending delivery that she begged for her infant to be taken away. [On left: Cover of “Diary of Montevue, 1893-1896.” (Box 111, Folder 2, GTM 119, Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus. Please note that the collection is currently being reprocessed; this citation conforms to the collection’s unrevised finding aid.)]

During my first week at the Booth Family Center for Special Collections, I stumbled upon four bound items labeled “Diaries of Montevue.” Dating from the 1890s, these station diaries chronicled the experiences of Jesuit novitiates serving the Catholic inmates at Montevue Asylum in Frederick, Maryland. Inserted into one of these volumes was a loose page titled “Information about Montevue,” dated June 21, 1897. It contained the brief account of Belle Reade, above. Reade, who may have suffered from postpartum depression after a previous birth, seems to have been so worried about her state of mind after her impending delivery that she begged for her infant to be taken away. [On left: Cover of “Diary of Montevue, 1893-1896.” (Box 111, Folder 2, GTM 119, Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus. Please note that the collection is currently being reprocessed; this citation conforms to the collection’s unrevised finding aid.)]

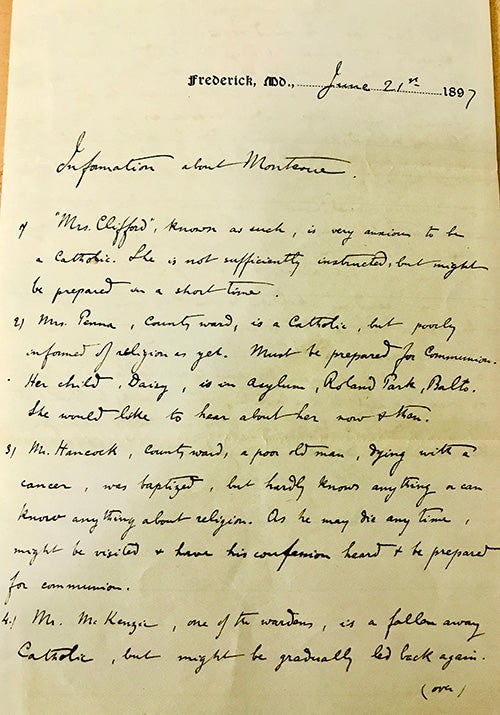

Reade was not the only woman at Montevue with a complicated relationship to maternity. The document also relayed the stories of “Mrs. Penna, a county ward,” and “a negress, named Rosie.” Mrs. Penna’s daughter, Daisy, was in a children’s asylum in Baltimore. “She would like to hear about her now & then,” the diarist wrote, though whether or not her desire was honored went unrecorded. The fate of Rosie, the mother of twins, was clearer. Though a Catholic who had ensured that her children were baptized, she was also described as “more than half-crazy.” As a result, it was determined that “the children ought to be sent to an asylum, as the Board will not allow her to keep them.” Whether she wanted to or not, Rosie would have to give up her children.

Founded in 1870, Montevue was a county-run complex that served as an almshouse for the poor, workhouse for detainees, and asylum for those perceived to have mental illnesses. It had separate wards for whites and for African Americans, along with a “tramp house” located behind the main building. It would, without a doubt, have been a difficult place to give birth and care for an infant.

Even so, the Frederick Jesuits recognized that poor women should have some say in whether or not their babies would be removed from them and sent to an “infant asylum” – or orphanage – in in Baltimore. The document went on to explain, “About sending children to an asylum, the best plan is to get the consent of the mother.” In the cases of Mrs. Penna and Rosie, however, this consent was “not required” – perhaps due to their mental health, extreme poverty, racial status, or a combination of all three.

Front and back of “Information about Montevue,”

June 21, 1897, inserted into the diary.

Apart from their brief appearances in the MPA, I have not discovered much more about these women. Belle Reade is mentioned three more times in the Montevue Diaries, in earlier entries from 1895, indicating the woman’s longstanding, or at least intermittent, presence at Montevue. On January 21, she was “very sick after child birth.” On February 16, she was “removed from the pauper [ward] to the ward for the insane,” presumably the experience that had made her so afraid of a subsequent birth. Though this suggests a link between childbirth and a vulnerable mental state, the diarist also conceded that “her insanity is more of stubbornness than anything else.” On February 23, a priest named Father Pendergast made arrangements for Reade’s baby to be “sent to infant asylum at Baltimore.” Her first child, as well as her second, had almost certainly been removed from her care.

We can learn a great deal from the Maryland Province Archives – about the history of American Catholics, about Jesuit slaveholding, about the ways in which Georgetown itself profited from the slave trade and from the labor of enslaved people. And, as I learned when I began my job, we can find mothers who confronted, willingly or not, separation from their children. It is certainly true that many, if not most, archival documents from the 19th century were created by those in positions of power. Even so, by reading closely, we can learn about the experiences of those who had all but fallen out of society’s precarious social safety net. Though Belle Reade, Mrs. Penna, and Rosie may have never created their own documents – and though we may never know what happened after they left Montevue, if they ever did – the MPA ensures that their lives and their struggles need not be entirely forgotten.

--Cassandra Berman, Archivist for the Maryland Province Archives