June, 2021

The Georgetown University Library offers a wide variety of primary materials for those interested in learning more about slavery, emancipation, and African American history. In honor of Juneteenth—the holiday celebrating the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States—Library staff are highlighting materials from the manuscript, art, rare book, and archives holdings of the Booth Family Center for Special Collections and the Woodstock Theological Library. If you would like to know more about these items, or our other collections pertaining to slavery, freedom, and beyond, please contact us.

Rare Books

The Rare Book Collections hold works by Black writers exploring freedom, enslavement, the antislavery movement, and emancipation. Slave narratives—harrowing autobiographical accounts of individuals’ experiences of enslavement, usually written after escape—were particularly instrumental in exposing slavery’s horrors and galvanizing antislavery activism.

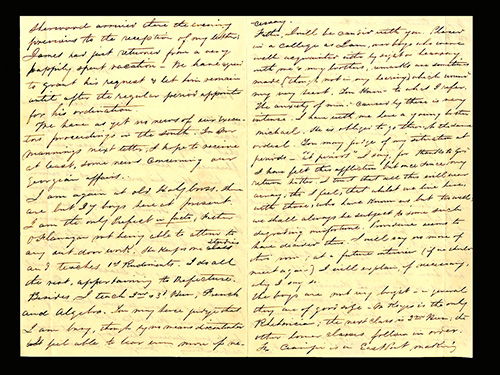

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, published in 1845, is perhaps the best known of these narratives. Taught to read the Bible by one of his enslavers, Douglass explores the impact of family separation, the violence of his enslavers on a Southern Maryland plantation, and the events leading to his escape to the North. The Narrative demonstrates the subversive power of literacy and the rationale for anti-literacy laws throughout the South. It quickly became a bestseller and solidified Douglass’s reputation as an exceptionally eloquent and insightful writer. Our 1846 copy of the work features a frontispiece portrait of Douglass, who would become the most frequently photographed American in the 19th century.

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (Boston, 1846).

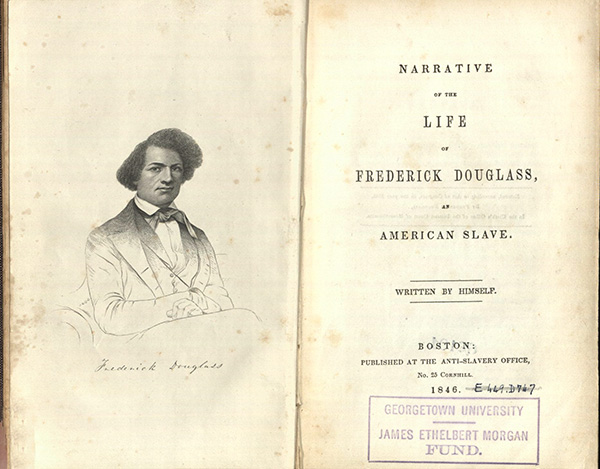

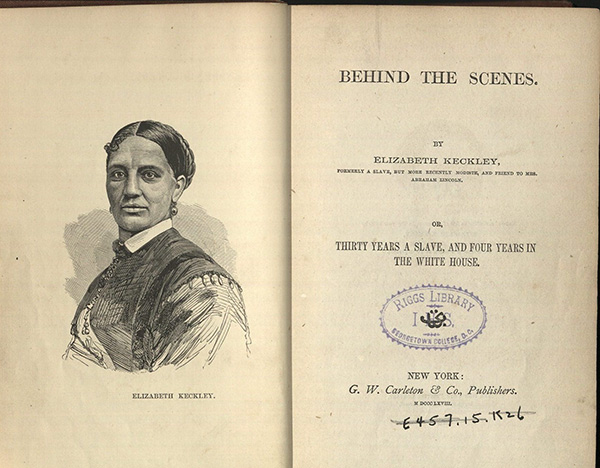

Narratives by formerly enslaved people were also published after the culmination of the U.S. Civil War. Such texts often showed the extremely varied life experiences and accomplishments of Black individuals both before and after emancipation. One such text is Elizabeth Keckley’s 1868 narrative, Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House. Born into slavery in 1818, Keckley became a successful dressmaker, and eventually used loans from her customers to purchase both her own freedom and that of her son. She moved to Washington, D.C. in 1860, set up a dressmaking shop, and became the dresser and personal friend of First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln. Our copy of Keckley’s narrative features the portrait of a successful businesswoman who was the close confidante of the most influential family in the country—and who had navigated life under enslavement, life as a free woman in slave society, and life after emancipation.

Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes, or Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House (New York: G. W. Carleton, 1868).

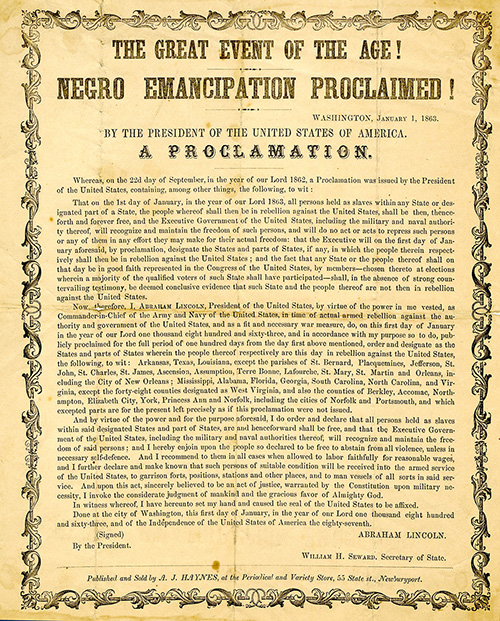

Our Rare Book Collections also contain a printed broadside of the Emancipation Proclamation. Such broadsides, widely produced and circulated, allowed members of the public to become intimately familiar with “The Great Event of the Age!”—the proclamation that declared enslaved people living in Confederate states to be free.

“The great event of the age! Negro emancipation proclaimed!

Washington, January 1, 1863,

by the President of the United States of America, A Proclamation”

Newburyport, R. I.: A. J. Haynes, 1863.

Manuscripts

The manuscript holdings of the Booth Family Center for Special Collections and the Woodstock Theological Library shed light on the lives of African Americans who lived and labored alongside the Jesuits in the mid-Atlantic region. Photographs from the Woodstock College Archives and the Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus provide a particularly arresting glimpse into the rich communal lives of Black Catholics in Maryland.

After emancipation, some Black Catholics in the Maryland region remained loyal to the church and in the employment of the Jesuits, their former enslavers. Many participated in church sacraments and rituals, took pride in their Catholicism, and found community in their congregations. They established and contributed financially to their own sodalities, benevolent associations, feasts, and parish fairs—carving a separate social space that enabled them to provide one another with spiritual care, charitable assistance, and a common voice to address grievances within their churches.

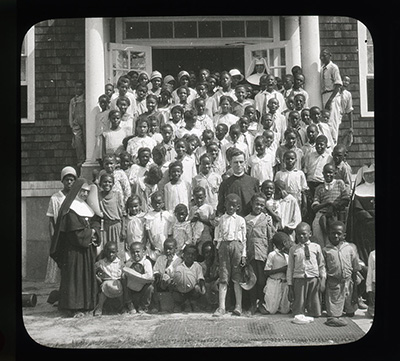

For example, at St. Alphonsus Church, which the Jesuits of Woodstock College ministered, Black people formed the St. Peter Claver Sodality. Its members reveled in the annual May Procession, a parade that honored Mary, the mother of Jesus. At St. Inigoes, the Black members of St. Michael’s Church separated from that parish to form St. Peter Claver Church. Its parishioners established a parochial school run by the Oblate Sisters of Providence to educate children of the poor agricultural community in that region. Both images—the May Procession and the Oblates portrayed with their students—suggest the importance of Black women in nurturing religious devotion and education in the 1920s and 1930s.

Dorothy Chance, Violetta Parker, Geraldine Parker, and Thomasene Chance

May Queen and Attendants, St. Peter Claver Sodality, Md., 1929

Woodstock College Archives, IP-3.5, Box 38

Horace McKenna, S.J. and members of the Oblate Sisters of Providence with students of St. Peter Claver School, St. Inigoes, Md., c. 1933

Unidentified photographer, image found in a slide show used by the Jesuit community at St. Michael’s Catholic Church, Ridge, Md.

Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus, Addenda Box 32

Click image to enlarge

Art

The University Art Collection holds a growing number of works by Black artists and about the Black community in America. The following pieces address the promise of emancipation both from the contemporary vantage point and from subsequent generations, who continued to fight for its full realization. The Library is actively collecting in this area.

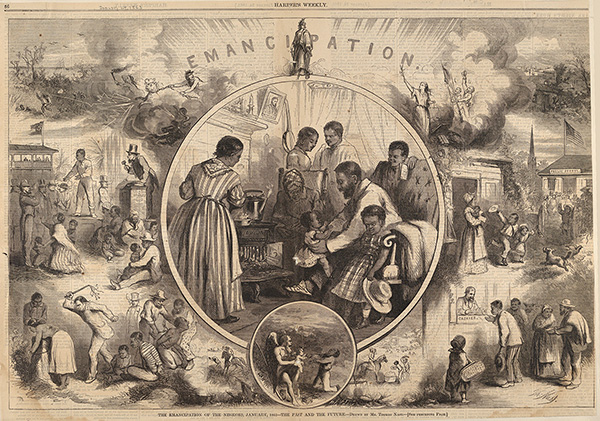

The Emancipation of the Negroes, January, 1863—The Past and the Future in Harper's Weekly

Thomas Nast

Wood engraving

Click image to enlarge

Thomas Nast’s The Emancipation of the Negroes, January, 1863—The Past and the Future, straddles the pre- and post-emancipation eras. Printed for Harper’s Weekly shortly after the Emancipation Proclamation, this piece by Nast illustrates the horrific abuses of slavery on the left (violence, fear, objectification), but also the hopes of emancipation on the right (wages, property, education). A Black family is centrally located in a vignette of domestic tranquility, foregrounding the promise of emancipation. In a smaller vignette underneath, a New Year’s baby breaks the chains of an enslaved man.

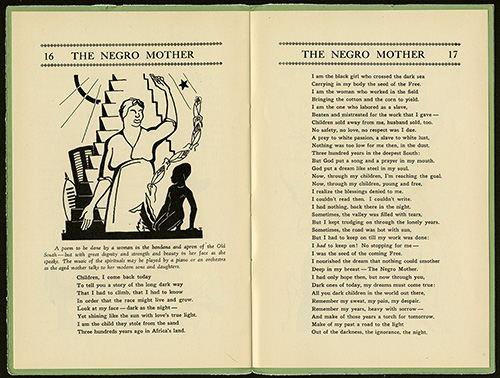

The Negro Mother

Prentiss Taylor, 1932

Print

Click image to enlarge

This work by Prentiss Taylor was printed in 1932 for Langston Hughes’ The Negro Mother and Other Dramatic Recitations, and graces both the cover and the titular poem. Prentiss’ print beautifully captures the spirit of the poem, which is written from the vantage point of a symbolic mother, encompassing the previous generations of the enslaved. It is a cry to the generation of the 1930’s not to forget their ancestor’s past enslavement, but to use that collective experience of oppression as an inspiration to face the obstacles of the present. It ends with the following hope-filled call:

Remember my years, heavy with sorrow -

And make of those years a torch for tomorrow.

Make of my pass a road to the light

Out of the darkness, the ignorance, the night.

Lift high my banner out of the dust.

Stand like free men supporting my trust.

Believe in the right, let none push you back.

Remember the whip and the slaver's track.

Remember how the strong in struggle and strife

Still bar you the way, and deny you life -

But march ever forward, breaking down bars.

Look ever upward at the sun and the stars.

Oh, my dark children, may my dreams and my prayers

Impel you forever up the great stairs -

For I will be with you till no white brother

Dares keep down the children of the Negro Mother.

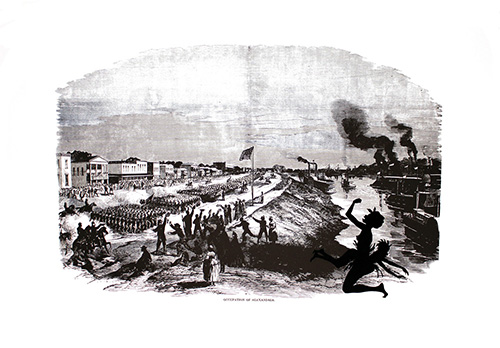

The Occupation of Alexandria from Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War

Kara Walker, 2005

Print

Click image to enlarge

Kara Walker’s The Occupation of Alexandria comments on the way in which narratives of the Civil War often place the Black community in the background. The silhouetted figure of a Black nude woman, with a child emerging from her back, foregrounds the monstrosity of slavery onto the typical historical narrative of heroic battles and military actions. At the same time, the figure of the child emerging calls to mind the new beginning and new freedom brought about by the abolition of slavery.

Georgetown University Archives

Extensive documentation can be found in the Archives and manuscripts collections regarding the career of Patrick F. Healy, S.J., who entered the Jesuit order in 1850 and served as president of Georgetown University between 1873 and 1882. Within these considerable holdings, only one document clearly acknowledges what is now widely recognized: he was the first Black president of any college in the United States.

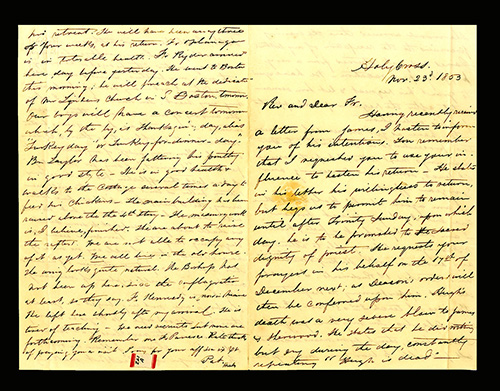

Patrick Healy was the third son of an Irish-American planter from Georgia, Michael Healy, and a woman enslaved by him, Mary Eliza Smith. Michael Healy sent Patrick to Holy Cross in 1844 with the intention that he “pass” as white. There was awareness among other students of Patrick’s racial ancestry. In a letter written on November 23, 1853 to George Fenwick, S.J, former teacher at Holy Cross who sold the people owned by his family in the 1830s, Patrick Healy confessed to “very intense” anxiety: “Placed in a college as I am, near boys who were well acquainted either by sight or hearsay with me & my brothers, remarks are sometimes made (though not in my hearing) which wound my very heart.” Acceptance by Fenwick, and probably by Jesuits who benefited from slavery, was critical for Patrick Healy and his siblings to pass as white. They needed to become part of the culture of slavery themselves.

For more information, see Patrick F. Healy, S.J.: Georgetown University President, 1873-1882, a guide to primary and secondary sources developed by University Archivist Lynn Conway.

Patrick Healy, S.J., c. 1873

Photograph by Julius Ulke

Patrick Healy, S.J., to George Fenwick, S.J., November 23, 1853

Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus, box 74, folder 1

Click images to enlarge

Cassandra Berman, Archivist for the Maryland Province Archives

Mary Beth Corrigan, Curator of Collections on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation

Adrian Vaagenes, Digital and Archival Services Librarian, Woodstock Theological Library